The Museum first opened its doors on 18 April 1881, but its origins stretch back to 1753 and the career of Sir Hans Sloane, a doctor and collector.

Sloane travelled the world as a high society physician. He collected natural history specimens and cultural artefacts along the way.

After his death in 1753, Sloane's will allowed Parliament to buy his extensive collection of more than 71,000 items for £20,000 - significantly less than its estimated value.

The government agreed to purchase Sloane’s collection and then built the British Museum so these items could be displayed to the public.

The Museum remained part of the British Museum until 1963, when a separate board of trustees was appointed, but it wasn't officially renamed the Natural History Museum until 1992.

Sir Richard Owen

In 1856 Sir Richard Owen - the natural scientist who came up with the name for dinosaurs - left his role as curator of the Hunterian Museum and took charge of the British Museum’s natural history collection.

Unhappy with the lack of space for its ever-growing collection of natural history specimens, Owen convinced the British Museum's board of trustees that a separate building was needed to house these national treasures.

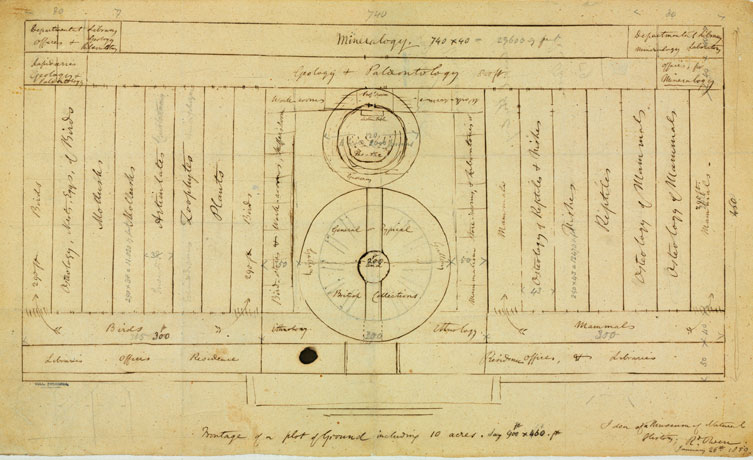

An rough architectural plan drawn by Richard Owen in 1859 entitled 'Idea of a Museum of Natural History'. The plan was referred to by Alfred Waterhouse in the creation of the Natural History Museum, London.

In 1864 Francis Fowke, the architect who designed the Royal Albert Hall and parts of the Victoria and Albert Museum, won a competition to design the Natural History Museum.

When he unexpectedly died a year later, the relatively unknown Alfred Waterhouse took over and came up with a new plan for the South Kensington site.

Waterhouse used terracotta for the entire building as this material was more resistant to Victorian London's harsh climate.

The result is one of Britain’s most striking examples of Romanesque architecture, which is considered a work of art in its own right and has become one of London's most iconic landmarks.

The Diplodocus affectionately known as Dippy was in the cental hall from the 1970s until 2017.

A cathedral to nature

While the building reflects Waterhouse’s characteristic architectural style, it is also a monument to Owen’s vision of what a museum should be.

In the mid-nineteenth century, museums were expensive places visited only by the wealthy few, but Owen insisted the Natural History Museum should be free and be accessible to all.

Victorian explorers’ regularly unearthed new species of exotic animals and plants from all over the British Empire, and Owen wanted a building big enough to display these new discoveries in what he called a cathedral to nature.

Owen's foresight has allowed the Museum to display very large creatures such as whales, elephants and dinosaurs, including the beloved Diplodocus cast that was on display at the Museum for 100 years.

He also demanded that the Museum be decorated with ornaments inspired by natural history. And he insisted that the specimens of extinct and living species kept apart at a time when Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution was revealing the links between them.

Along with incorporating Owen’s ideas into his plans, Waterhouse also designed an incredible series of animal and plant ornaments, statues and relief carvings throughout the entire building – with extinct species in the east wing and living species in the west.

The sculptures represent amazing creatures from nature’s diverse past, such as the ancient Great Palaeotherium and Pterodactyl, as well as present-day animals including the lion and cobra.

Waterhouse sketched every one of these sculptures in great detail, even asking Museum professors to check the scientific accuracy of his drawings, before creating the fantastic decorations that complement the Museum’s exhibitions.

The intricate ceiling of Hintze Hall

Hidden treasures

High above the Museum’s main attractions there's another decorative feature that's easy to miss, unless you know where to look.

The building's gallery ceilings are adorned with intricate tiles displaying a vast array of plants from all over the world, with Hintze Hall's ceiling alone covered with 162 individual panels.

These beautifully designed tiles reflect an era when exotic plant specimens flooded into Britain, sparking public interest in botany and horticulture.

The Darwin Centre lit up at night

Evolution of the Museum

In 1986, the Museum absorbed the adjacent Geological Museum of the British Geological Survey and its collection of more than 30,000 minerals. The Lasting Impressions gallery opened three years later to connect the two buildings.

The Darwin Centre opened to the public in 2009 and houses the Museum's historic collections as well as its working scientists. The centre's unique Cocoon structure displays the Museum's most important plant and insect specimen collections, and is equipped with state-of-the art research facilities used by more than 200 scientists.

Visitors can watch our scientists work in open-plan laboratories, where they study everything from the cocoa that Sloane brought back from Jamaica in the seventeenth century to malaria-carrying mosquitoes collected in 2008.

Hintze Hall, the Museum's central space, was redeveloped in 2017. The Diplodocus skeleton cast was replaced with a 25.2-metre blue whale skeleton. It is intended to be a reminder to visitors that humanity has a responsibility to protect the biodiversity of our planet.

Our galleries

Discover the permanent galleries and find out how to get around the Museum with our map.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media