In 1927 Museum staff commandeered trains to transport 126 false killer whales from Scotland to South Kensington.

It's not the most conventional cargo - but staff specialising in cetacean strandings are used to the unorthodox.

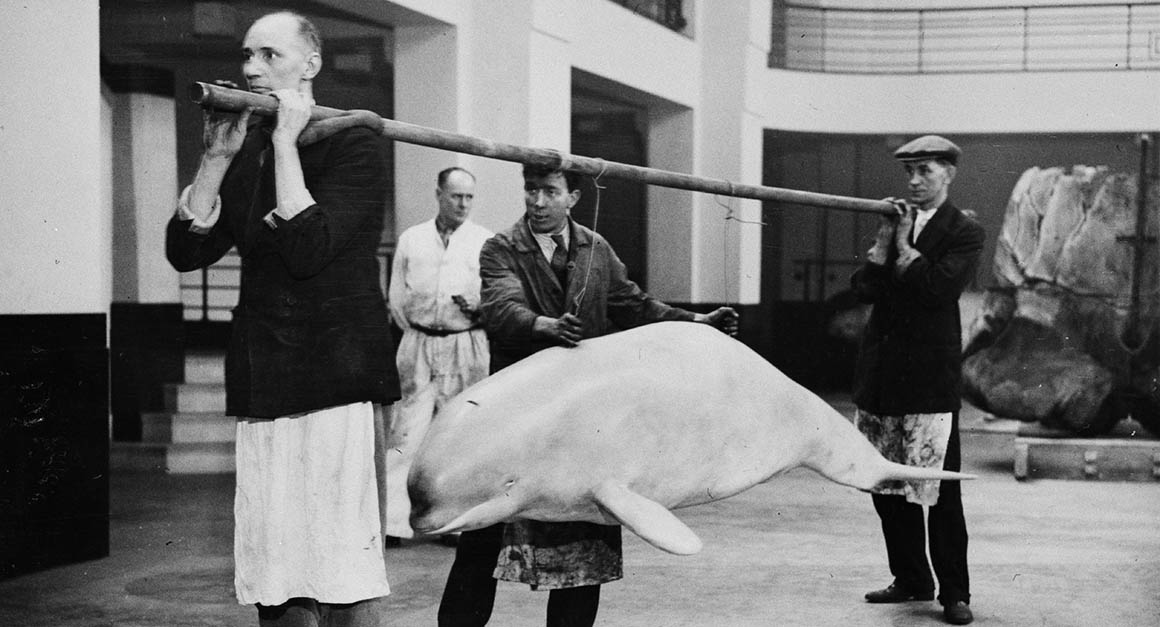

Museum staff carry a model beluga on a pole, around 1934

In 1927 Museum staff commandeered trains to transport 126 false killer whales from Scotland to South Kensington.

It's not the most conventional cargo - but staff specialising in cetacean strandings are used to the unorthodox.

Since 1913, scientists have been given priority access to any cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises) that end up stranded on Britain's coastlines.

Until then, the Fishes Royal statute of 1324 had declared the British monarch the owner of all cetaceans and sturgeons in the waters around the UK.

Richard Sabin, a whale expert at the Museum, says 1913 marked a turning point both for the Museum's collections and for our scientific understanding of these marine mammals.

'Until this agreement was put in place, the law prevented scientists from touching the carcasses,' Richard says.

'Opportunities were being missed to understand and research the animals, which were washing up in great numbers.

'The early collection of material allowed researchers to get a better idea of the anatomy, biology and ecology of everything - from blue whales to harbour porpoises, and everything in between.'

Since then, experts have documented 17,500 cetacean strandings. To date 28 different species of cetaceans have been recorded around the British Isles, representing almost a third of the total 90 species identified around the world.

'We have more than 2,500 specimens in our research collection and at least 500 of those are from the UK strandings programme,' Richard says.

Collecting cetaceans large and small proved a logistical challenge for the pioneers of the Museum's strandings programme, especially in the days before refrigerated transport.

Richard says, 'Back in the early days it was bulk collecting, but usually only of the smaller species. It's always been really hard to collect the big things.'

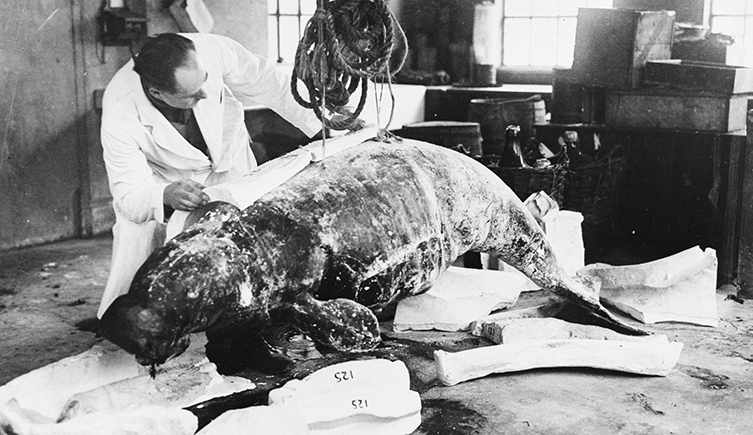

Until 1990, the protocol was to create plaster casts of stranded cetaceans to produce anatomically correct moulds for the collections.

To reduce the changes caused by deterioration, casts were made from the bodies of large cetaceans and other mammals - such as this rare dugong, pictured here in 1924 - as soon as they arrived at the Museum

An example of the Museum going to great lengths to gather specimens is when more than 130 false killer whales were stranded over the course of just one week in October 1927 in Dornoch Firth, Scotland.

At the time thought to be extinct, false killer whales had previously only been described from fossil specimens in 1846 by the Museum's first Director, Sir Richard Owen. So when a mass stranding was reported, Martin Hinton, then the Keeper of Zoology, went up to investigate.

'Our predecessors went up there and worked with local people to identify and record each and every carcass,' Richard says.

'Ranging in size from four to six metres, the animals were largely dissected and then sent down to London by train to King's Cross. Skeletons from 126 of the animals are now in our Cetacea research collection.'

'False killer whales were very poorly known and understood, and an entire pod added something incredibly valuable to the research collection.'

The unusually named false killer whale is actually a member of the dolphin family Delphinidae and is the fourth-largest dolphin © Juan Ortega, licensed under CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

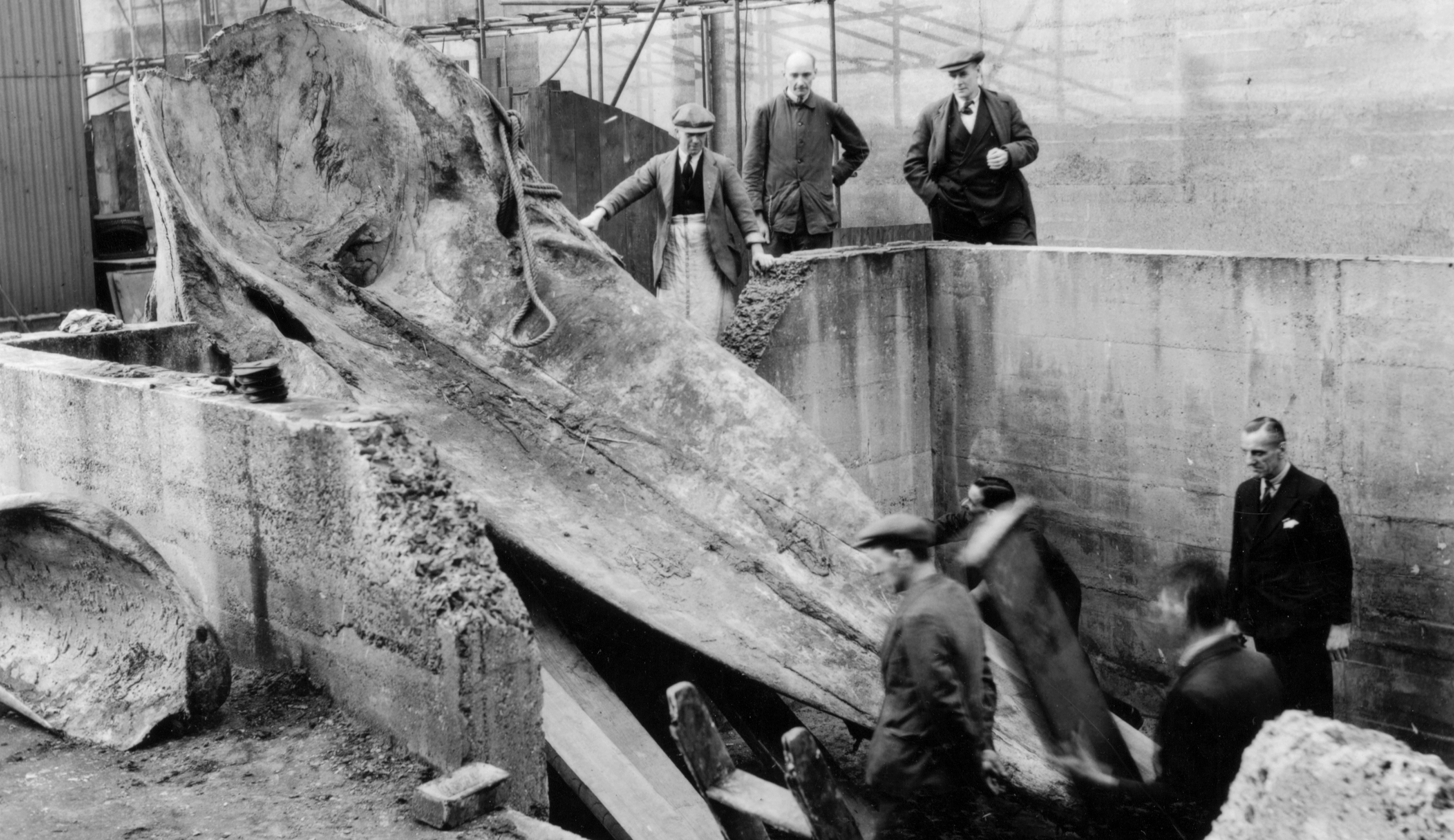

In the early decades since the abolition of the Fishes Royal statute in 1913, cetacean carcasses were buried in sandpits in the northwest corner of the Museum grounds, roughly where the Darwin Centre is now. Larger specimens were buried and left to decompose so that their skeletons could be added to the collection.

The last specimen to receive this treatment was a sperm whale that arrived in February 1937 from Bridlington, Yorkshire. In this photograph from 1938, Museum staff are digging it up before cleaning and placing the bones in the research collection, where they remain to this day.

This five-metre-long sperm whale skull was the last specimen to receive treatment in the South Kensington burial pits. This photo was taken in 1938 and the burial pits were not reactivated after the Second World War.

During both First and Second World Wars scientists at the Museum were asked to lend their expertise to matters of national defence. Sir Sidney Harmer, Museum Director from 1919 to 1927, was asked by the War Office to investigate the nutritional properties of porpoise meat for troops in the field.

'They acquired a freshly dead porpoise that was delivered to London, where it was apparently prepared by a reputable chef,' Richard quips.

'They then served up to London's best and brightest - scientists and generals and goodness knows who else. As you can imagine, it was quickly written off as being a bit too gamey and salty for the troops.'

In 1990 the UK government launched the UK Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme (CSIP) to coordinate the reporting and post-mortem examination of cetaceans stranded along the British coastline. The Museum is a partner and has a dedicated project team.

Louise Allan, Cetacean Strandings Support Officer at the Museum, describes the process of handling a stranding:

'If it is a live animal the British Divers Marine Life Rescue are called in, as they have specially trained members who can help. If the animal is dead we [CSIP] are informed about it. What happens next depends on what has washed up and how decomposed it is.

'If it's fresh and small enough to be transported we will try and collect it for post-mortem examination to determine cause of death. If it's a large whale it will be examined on the beach.'

On average there are between 550 and 600 stranded cetaceans each year. CSIP facilitates post-mortem examinations on a quarter of these animals, providing scientists with a rich data set.

As large cetaceans are particularly difficult to study in the wild, CSIP has helped shed light on reproductive patterns, diet and interactions between species, as well as disease, levels of environmental contaminants and other current threats facing these animals.

According to Louise, strandings can be good news for some species. For example, in 1982 and 1985 the first strandings of humpback whales in over 100 years were recorded.

Since 2001 there have been more regular strandings of humpbacks along the UK coastline, indicating that populations are recovering thanks to an embargo on commercial whaling.

'In some cases increased numbers of strandings can actually be an indicator that a population is bouncing back,' Louise explains.

With one of the most extensive cetacean specimen collections in the world, the Museum remains affiliated with the strandings programme. Additions to the collections are much more focused now, however.

'Today we have a wish list of species, and as a result I'm called in when these appear,' Richard says.

'We have a lot of adult animals represented, so any time there is a chance to collect a foetus or newborn from a dead female we will do that, as these are hugely informative developmental stages and critical for our research.'

The strandings programme has helped form a sophisticated network of partner organisations around the country, allowing scientists to respond rapidly to reported strandings. The public also play an important role in reporting and identifying stranded cetaceans.

'One of the great things about the project for me is the public involvement, but we have to tread a fine line with health and safety,' Richard says.

'It's incredible, the lengths that people will go to try to secure a carcass.

'There is something about suddenly finding the body of a whale or dolphin on the beach. These things have been a source of mystery to us for millennia and when they pitch up on our turf we are fascinated by them.

'There is this amazing sort of empathy there, the sense of one intelligent animal trying to understand how another intelligent animal met its end in such a way.'

Find out what to do if you spot a stranded cetacean on the shoreline.

Visit the Museum to walk beneath the largest animal ever to have lived.

Find out more about life in the ocean, and explore the Museum's pioneering marine science.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media