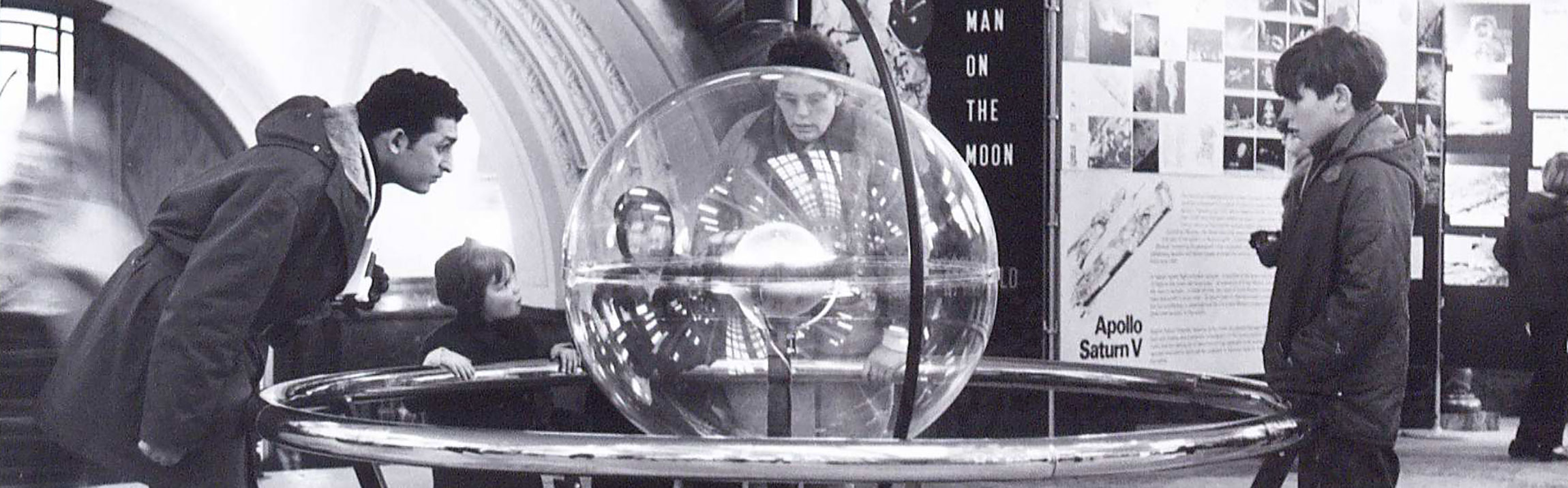

The Natural History Museum has exhibited pieces of Moon from multiple Apollo missions over the years. Here’s a shot from the 1970s, when our Red Zone was a separate Geological Museum.

undefinedIn pictures: Apollo missions and the Natural History Museum

Jordan Risebury-Crisp and Lisa Hendry

Forty-seven years after it was collected from the surface of the Moon during the last Apollo mission, the Natural History Museum still treasures the fragment of lunar rock gifted to the UK.

But our history is further entwined with NASA’s Apollo missions. We took a trip into our archives to see how.

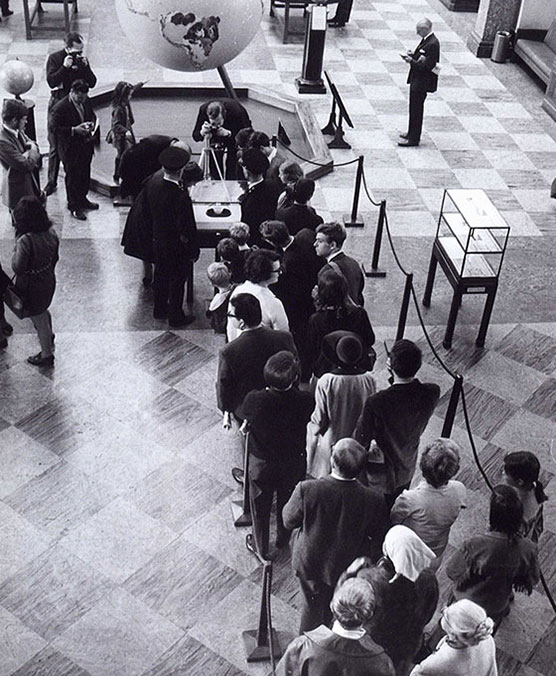

Around 35,000 people queued up on 20 and 21 September 1969 to see the dish of dust brought back by Apollo 11 from the lunar surface.

Although it’s a consistent feature of the night sky, the Moon holds many mysteries. In early 1969, at the peak of the space race, the USA set about trying to find some of the answers with their crewed missions to the lunar surface.

“The Eagle has landed”

On 20 July 1969, the historic Apollo 11 space mission landed on the Moon. Around six hours later, Commander Neil Armstrong became the first person to ever set foot on the lunar surface, watched by an estimated 650 million people worldwide.

As well as leaving us in awe of such a momentous endeavour, inspiring new generations of space scientists, and entering phrases such as “The Eagle has landed” into our common vocabulary, the mission fulfilled a number of key scientific goals.

One such objective was to gather samples of lunar-surface material for return to Earth, which astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin successfully did.

Moon dust at the Natural History Museum

Just two months after the Apollo 11 Moon landing, the Geological Museum – now our Red Zone – held a special weekend event which exhibited a small dish of Moon dust.

This dish represented the UK’s share of lunar material for study by scientific facilities.

The British public were overcome with Moon-fever and a reported 35,000 people visited over two days to view this heavily guarded dish.

Guards watching visitors admiring the dish of lunar dust brought to Earth by Apollo 11.

Just four months after the first Moon walk, Apollo 12 successfully touched down for a second crewed lunar landing.

During two lunar explorations, Commander Charles Conrad Jr and Alan L Bean collected further rock and dirt samples as well as a 41-centimetre-deep core sample. They landed back on Earth on 24 November 1969.

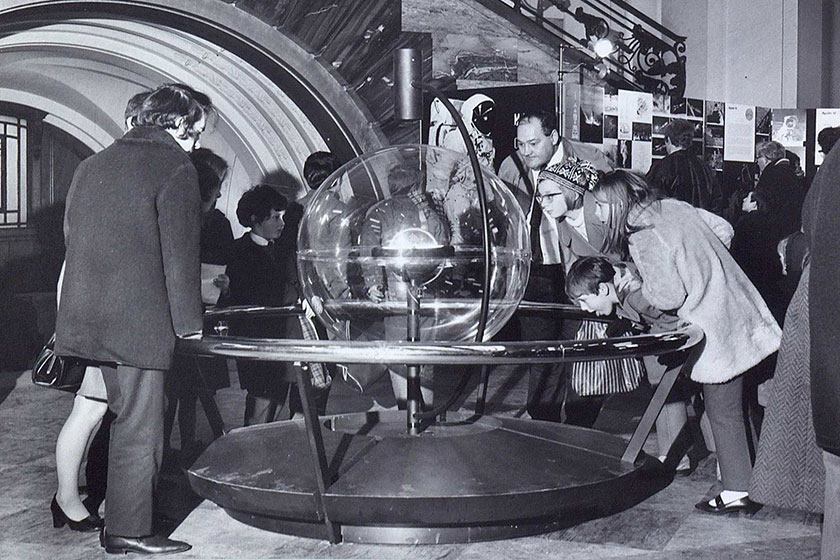

Between 27 December and 3 January 1970, the Geological Museum – which only merged with the adjacent Natural History Museum in 1986 – displayed a walnut-sized Moon sample, attracting 52,000 people. The Moon rock was accompanied by a free exhibition about the ongoing Apollo missions and the work being carried out on returned lunar material.

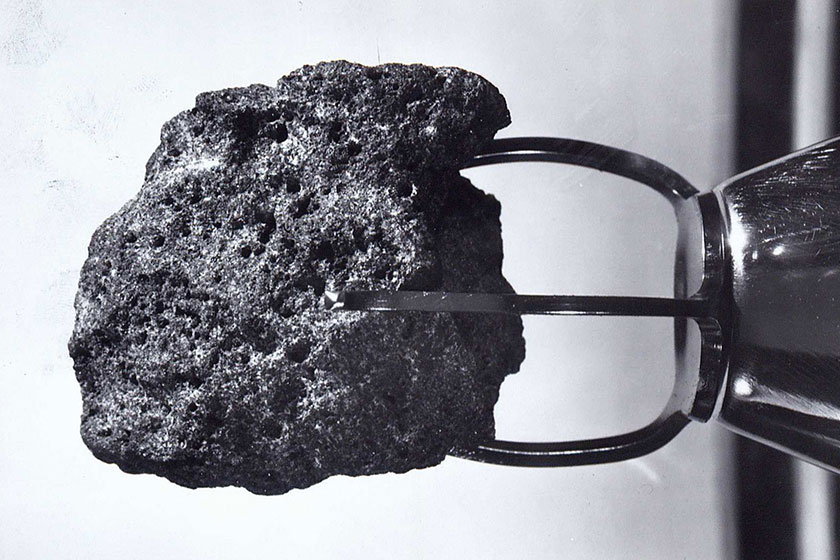

This walnut-sized piece of Moon rock was displayed at the Geological Museum from 27 December 1969.

Crowds flocked to see the 34-gramme sample of basaltic lunar rock, which was encased inside an 81-centimetre Plexiglass sphere.

An opportunity missed

In 1970, a year after the Apollo 11 crew collected the first lunar samples, US President Richard Nixon presented the UK with a gift of four lunar dust grains, about the size of rice grains.

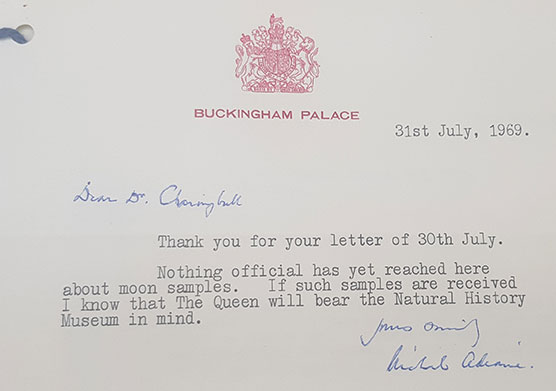

The Natural History Museum Director at the time, Dr GF Claringbull, learned of Nixon’s plan in advance and tried to secure a piece of the Moon for the collections we care for. Less than a week after Apollo 11 returned to Earth, he wrote to Buckingham Palace asking the Queen to consider us as recipients of any gift:

“I note from press reports that President Nixon intends to give samples of the moon to Heads of State and no doubt the Queen will be among the first to receive one.

The Palace’s message to then-Director GF Claringbull.

I venture to suggest that should Her Majesty consider putting the specimen on public display this Museum would be the most appropriate place. As you will know, we have the national collections of minerals, meteorites and rocks. Our mineral collection is thought by many, including the Americans, still to be the best in the world, and we have undisputably [sic] the most representative collection of extra-terrestrial matter in the form of meteorites in any Museum.”

-GF Claringbull, 30 July 1969

The response from the Palace, a day later, was:

“Nothing official has yet reached here about Moon samples. If such samples are received I know the Queen will bear the Natural History Museum in mind.”

As it happened, the UK sample was presented not to the Queen but to Prime Minister Harold Wilson. It reportedly remains somewhere in 10 Downing Street today.

However, a few years later, the Natural History Museum received an equally special gift.

The Goodwill Moon rock

The Apollo missions ran until December 1972. Six missions landed on the Moon and returned lunar material to Earth.

In 1973, larger samples from the last crewed mission – Apollo 17 – were distributed as further goodwill gifts to 135 countries around the world.

The UK gift consisted of a thumbnail-sized piece of the Moon mounted on a plaque with a Union Jack flag that had accompanied the Apollo 17 astronauts into space.

Having reached out to the UK government about acquiring the sample for the collections we care for, Director Claringbull was this time successful.

Beneath the UK’s Apollo 17 Goodwill Moon rock a message says it’s given “as a symbol of the unity of human endeavour and carries with it the hope of the American people for a world at peace”. The panel also provides details of where the fragment was collected.

Today, this piece of the Moon resides alongside other extraordinary specimens in the Treasures gallery here at the Natural History Museum. It’s the only piece of Moon rock in the UK from NASA’s last Apollo mission.

Geologist Harrison Schmitt – the only professional scientist to reach the lunar surface – collected it from the Taurus-Littrow Valley of the Moon. He trained all the other astronauts on how to collect samples.

Our space scientist Professor Sara Russell considers herself very fortunate to be able to study fragments of the Moon.

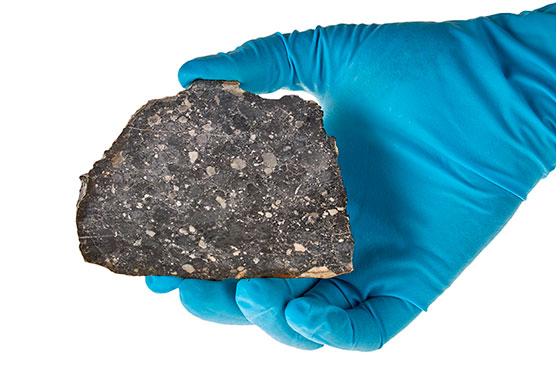

“This is special. It’s one of very few rocks from the Moon that we have in the UK, or even on Earth,” she says of the Apollo 17 rock.

“It’s a crystalline rock and you can see the individual crystals glinting in the light, but overall it’s very dark in colour. It’s almost black.”

“When you look up to the Moon you can see that it’s mostly light grey, but it has big circles of dark material, made up of a rock called basalt. This is likely to be a piece of the basaltic Moon.”

From the near-side of the Moon

In total the Apollo missions collected 2,200 lunar samples weighing 382 kilogrammes from six different lunar sites on the side of the Moon nearest Earth.

Other than the small samples presented as gifts, all Apollo rocks belong to the US and are maintained by the Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science team at the Johnson Space Center.

However, the Natural History Museum is lucky to also have a piece from Apollo 16 on long-term loan.

Photograph from the 1970s showing visitors admiring a piece of the Moon collected during the Apollo 16 mission. The specimen can still be seen in our Earth Hall.

This rock is called an anorthosite breccia. The pale grey areas of the Moon are made of anorthosite. Breccia means that it is made from bits of rock that were broken up and then fused together by pressure and heat.

Lunar meteorites

One of a handful of lunar meteorites cared for in the collections we care for.

The Apollo 17 Goodwill Moon rock isn’t the only lunar material in the collections we care for here at the Natural History Museum.

We also have lunar meteorites. These were created when impacts to the lunar surface sent rock fragments out into space that eventually landed on Earth.

“Before we went to the Moon, we didn’t really have a very clear idea of what it was. So much so, that although bits of the Moon do come to the Earth as meteorites, at that time they just weren’t recognised, because we really didn’t know what a piece of the Moon would look like,” Sara explains.

Some of the lunar meteorites here at the Natural History Museum may come from areas unexplored by NASA’s Apollo or Russia’s Luna collection-retrieval missions – such as the far side of the Moon.

Research continues on these samples to learn more about the origin and early evolution of the Moon and its twin, Earth.

Come face to face with a piece of the Moon

You can see the piece of Apollo 16 Moon rock in Earth Hall, near the Stegosaurus skeleton.

Visit Treasures to see the UK’s Goodwill Moon rock collected on the final Apollo mission.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media