The Crystal Palace park includes the world's first full-scale reconstructions of dinosaurs

undefinedThe world's first dinosaur park: what the Victorians got right and wrong

Emily Osterloff

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs might look comically incorrect, but they hold an important place in the history of palaeontology and at the time of construction were as accurate as was possible based on the scientific data available.

Natural history artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins unveiled his dinosaur sculptures in 1854. These were the world's first full-scale reconstructions of dinosaurs and represent the first three species discovered.

Dinosaurs were still a relatively new discovery in the mid-1800s. There were very few fossils to study and limited knowledge of what these prehistoric reptiles might have been like in life.

But just how much did Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins and his scientific advisors get right and wrong about these prehistoric reptiles? Dr Susie Maidment, a dinosaur researcher at the Museum, explains.

Designing dinosaurs

The best-known of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's numerous sculptures in Crystal Palace, southeast London, are the four dinosaurs: one each of Megalosaurus and Hylaeosaurus, and two Iguanodons. At the time of the sculptures' construction in the 1850s, there were very few remains of these animals to work from. Although Waterhouse Hawkins and his advisors knew they were reptiles, we now know that some of the men's theories about dinosaurs weren't quite right.

Susie says, 'I think really what they did was take things that they knew, like crocodiles and lizards, and blow them up to be the size of the bones.

'Big things today tend to be four-legged and relatively bulky. A gracile two-legged thing was completely beyond anybody's understanding of what a reptile could be.'

When the Crystal Palace sculptures were constructed, it was thought that Megalosaurus walked on four legs

The Crystal Palace Megalosaurus may have been modelled on a large reptile, such as a monitor lizard

© Rohit Naniwadekar via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Megalosaurus's four-legged form may have been based on monitor lizards (genus Varanus), some of the largest lizards in the world.

'There is still no complete Megalosaurus skeleton. It's known from lower jaws, hind limbs, and a few other bits. There's enough evidence to know that it's part of a group called Megalosauridae, which we know much better.

'They were bipedal and had small forearms, and rather than the elongate, crocodile-like skull the sculpture has, they probably had a much deeper skull.

'But given they didn't know anything other than these very few bones and didn't have any context, it's not unreasonable to construct Megalosaurus as they did,' explains Susie.

With the data available today, palaeontologists now know that Megalosaurus was a bipedal dinosaur

© Elenarts via Shutterstock

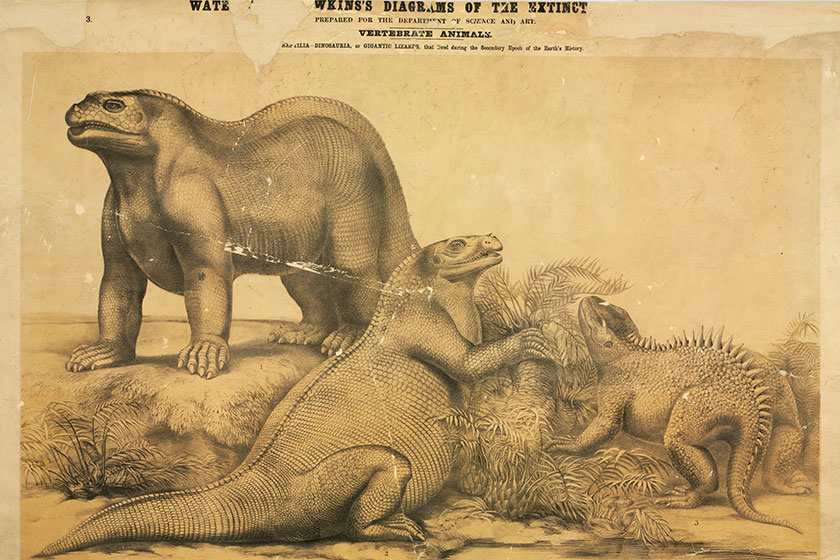

Waterhouse Hawkins's Iguanodon also looks nothing like its real-life counterpart. This dinosaur was named after its iguana-like teeth, found by Mary Ann Mantell in 1822, and its body may have been modelled on an iguana as well.

Susie explains, 'It's a similar story, really. They found the teeth and recognised they belonged to a reptile, and they found a few other bits and bobs like femora and vertebrae, so they knew they had a big reptile.

'They found the spike and stuck it on the end of the nose, a bit like a rhinoceros. It's all based on analogy.'

The Iguanodon sculptures at Crystal Palace were the best possible reconstructions of these dinosaurs with the data available at the time

© Peter Cooper via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Iguanodon was named for it's iguana-like teeth. The Crystal Palace Iguanodons may have been modelled on these reptiles as well.

© William Warby via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

It wasn't until a landmark discovery of Iguanodon fossils in Bernissart, Belgium, in 1878 that the famous spikes were moved to their rightful place on the dinosaurs' hands. But even with this new knowledge, not all was right with Iguanodon.

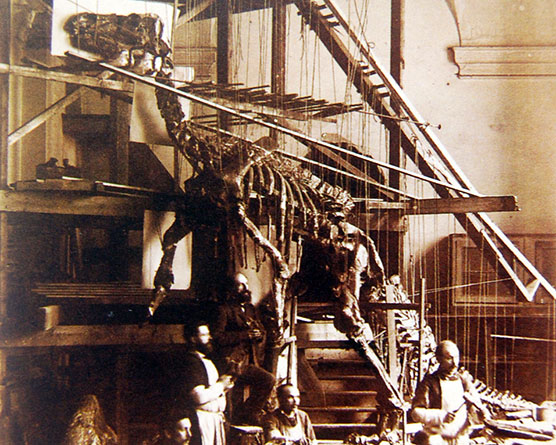

When the Bernissart Iguanodons were reconstructed in the 1870s, these dinosaurs were thought to have a kangaroo-like posture

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Palaeontologists in the 1870s determined Iguanodon would have had a kangaroo-like posture, although we now know that these animals were predominant quadrupeds, walking on the hoof-like ends of their fingers. This makes the Crystal Palace Iguanodons correct in their four-leggedness, albeit for the wrong reasons.

The most obscure of the three dinosaurs in the park is Hylaeosaurus, described by Gideon Mantell in 1832. Only one specimen of this dinosaur has ever been discovered.

Susie says, 'What we know today is based on recognising that the fossilised spikes, plates and particularly the shape of the scapulae are characteristic of ankylosaurs.'

In his 1833 book, The Geology of the South-East of England, Mantell stated that 'there appears every reason to conclude that either its back was armed with a formidable row of spines, constituting a dermal fringe, or that its tail possessed the same appendage, and was enormously disproportionate to the size of its body.'

In Waterhouse Hawkins's reconstruction, the spikes are located along the spine. In life these and armour plates would have been found across the animal's back or sides.

Susie explains, 'Back then they just had a neck and forearms, or at least a pectoral girdle, and they knew it had some spikes on its body. So what do you do? You take a crocodile or lizard, put some plates on it and you end up with a fairly reasonable reconstruction.'

In the park, Hylaeosaurus faces away from visitors. The Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs - the group that promote the long-term conservation of the Crystal Park statues and wider geological site - suggest that this might have been due to the lack of skull material for Waterhouse Hawkins to use as a guide for the models.

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's diagrams of Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus

Hylaeosaurus may have been positioned facing away from the public due to the lack of skull material from this dinosaur

© Simon Q via Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Scaly skin

Despite their well recorded flaws, some parts of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs are correct.

For instance, Waterhouse Hawkins's models are covered in neat scales. For Hylaeosaurus and Iguanodon, this is almost certainly accurate.

'There are a couple of ornithischian dinosaurs that have sort of integumentary structures, but they tend to be more like bristles. Not covering the whole body, just on the ends of the tails or something like that. But we don't have any evidence for that in Iguanodon or Hylaeosaurus,' explains Susie.

There is plenty of evidence of scaly skin in impressions left by hadrosaurs, close relations of Iguanodon. Stegosaurs were also scaly, suggesting that the same was likely of their ankylosaur cousins like Hylaeosaurus.

'These are reptiles. If we exclude birds, which they didn't know were dinosaurs at this time, reptiles are exclusively scaled. Snakes, lizards, Sphenodon - they all have scales, so it's reasonable to give the models scaled skin and it's still kind of our best bet today.'

This is a fossilised impression of Edmontosaurus skin. This dinosaur was a close relation of Iguanodon, so it's possible that they would have shared features, such as scaly skin.

What colour were dinosaurs?

We don't know everything about dinosaurs, so some aspects of the Crystal Palace models are up for debate. For example, the dinosaurs have been painted a variety of shades over the years.

Susie says, 'We'll probably never know the colour of dinosaurs with scaly skin.

'The way that they're looking at colour in feathers is by these structures called melanosomes. The shape of those code for colour. People have found melanosomes in scaly skin, but there isn't a good correlation between colour and shape in those melanosomes.'

The dinosaurs depicted in the Crystal Palace Park could very well have been green, but we may never know for sure.

Why is palaeoart important?

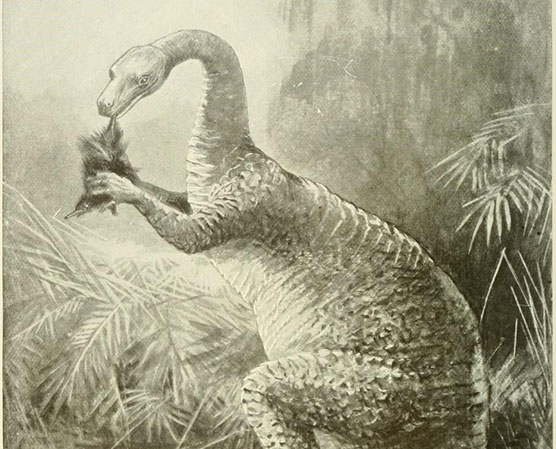

A reconstruction of Megalosaurus from The Book of the Animal Kingdom, published in 1910.

© Biodiversity Heritage Library via Flickr (CC0 1.0)

For non-dinosaur experts it can be tricky to look at isolated fossil bones and imagine a dinosaur. It would have been especially so for Victorians, when dinosaurs were a brand-new discovery.

Palaeoartists take those bones and create artworks that show the animals as they would have been in life, often with painstaking attention to the latest scientific understanding.

Susie says, 'You can't just imagine these animals, you need a visual representation of what they looked like and I think from that point of view palaeoart is really important.'

Like in Crystal Palace Park, over the last 150 years, palaeoartists haven't always got things quite right. For example, there are a number of reconstructions of Megalosaurus and Iguanodon facing off in dramatic battles.

We now know that although both dinosaurs were once found in Britain, they lived about 40 million years apart.

'Geologists knew that these dinosaurs were found in different rocks, but they had no real idea of the geological timescale and how old these rocks were,' Susie adds. 'Some still believed Earth was 4,000 years old. The amount of time between these rocks could have been days, weeks or years. '

Even today, palaeoart is incredibly important for several reasons. 'You can't have a children's book about dinosaurs without pictures inside, but palaeoart is also increasingly the best way of communicating what we do with the public.'

Édouard Riou's reconstruction of a battle between Iguanodon and Megalosaurus featured in Louis Figuier's 1864 book, La Terre Avant Le

© Fondo Antiguo de la Biblioteca de la Universitaria de Sevilla via Flickr (CC0 1.0)

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins and Crystal Palace Park

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs were the creation of one of the best-known natural history sculptors of his time, Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (1807-1894).

Waterhouse Hawkins's dinosaur sculptures were commissioned in 1852 and the finished models were unveiled to the public in 1854. These then-obscure animals were built with advice from Sir Richard Owen, the first Superintendent of the Natural History Museum and the man who put Iguanodon, Megalosaurus and Hylaeosaurus together into a new group called Dinosauria in 1842.

George Baxter's colour print of the Crystal Palace after its move to Sydenham, with some of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkin's sculptures featured in the foreground

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs are joined by a number of other prehistoric animal sculptures designed by Waterhouse Hawkins.

These include the giant ground sloth Megatherium, the Irish elk Megaloceros, as well as a number of other reptiles including Ichthyosaurs, Mosasaurus and pterosaurs. In 2023, a model of the extinct mammal Palaeotherium magnum was recreated and placed in the park, with the original having disappeared in the 1960s.

These models and more are placed around Crystal Palace park, ordered by their associated geological period.

The sculptures were built on the grounds of the Crystal Palace when it was relocated to Sydenham. Originally the Crystal Palace stood in Hyde Park, about 15 kilometres away, built to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The sculptures have long outlasted the historic Crystal Palace building, which was destroyed by a fire in 1936.

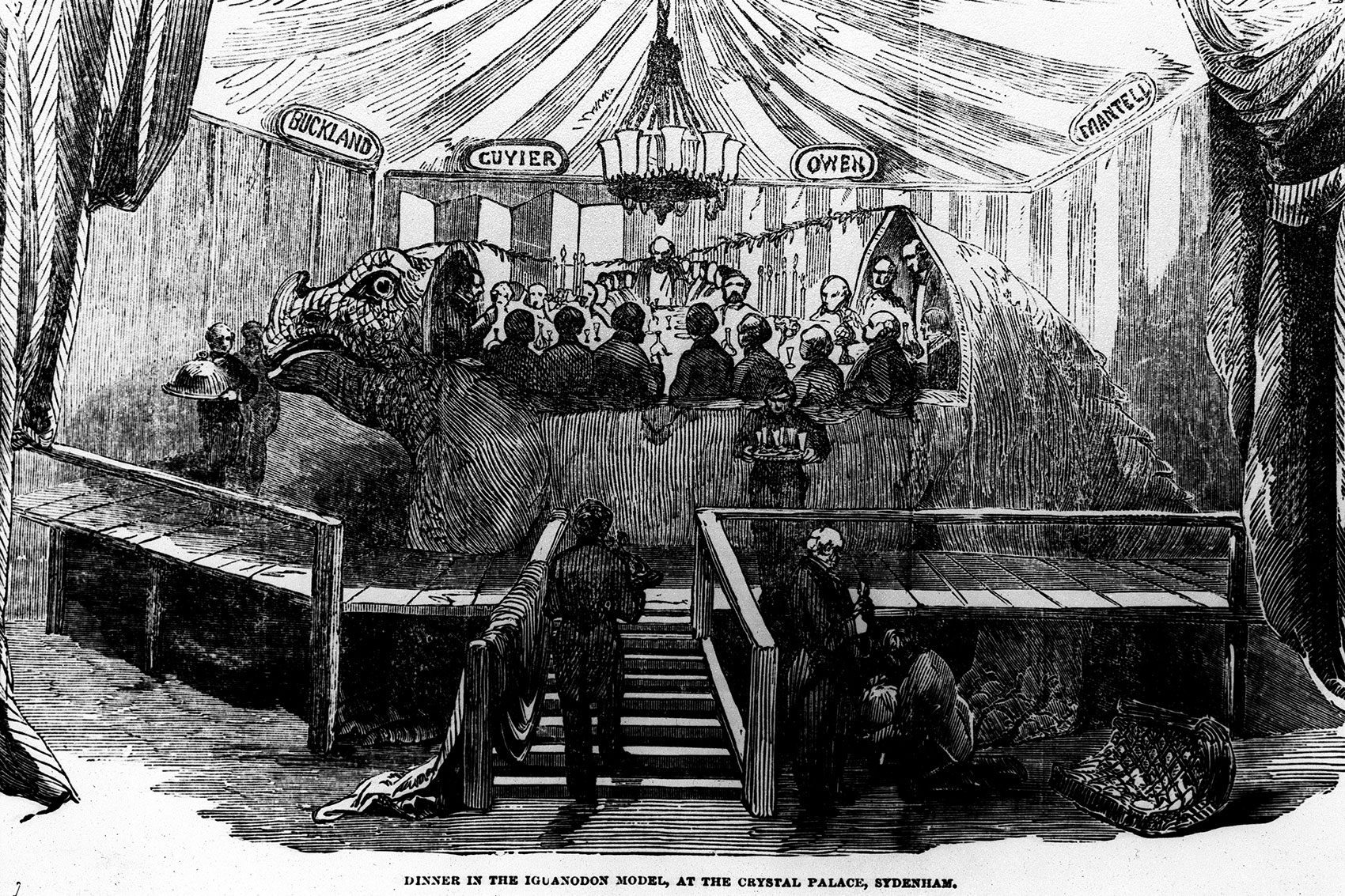

On 31 December 1853, before the dinosaurs were officially unveiled to the public, Waterhouse Hawkins hosted a banquet to celebrate their launch inviting scientists and officials of the Crystal Palace Company. The dinner took place inside the mold of one of the Iguanodon sculptures.

After over 150 years exposed to the elements, the sculptures deteriorated, and major conservation work has been carried out to try to restore the dinosaurs to their former glory. As of 2007, the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs have been awarded a Grade 1 listed status owing to their importance.

The areas around the sculptures in the park are currently being planted with vegetation that reflects the eras when these animals lived.

An engraving of the dinner held by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins in a Crystal Palace Iguanodon mold.

Susie says, 'They are three iconic dinosaurs that go back to the origin of Dinosauria, so they're incredibly important from a historical perspective in terms of where the science has come from.

'I think they capture lots of people's imaginations and lots of people go to Crystal Palace to see them - they're still a great advert for what we do.'

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media