A young Leanne Melbourne never thought she would grow up to be a scientist. Now she's a lecturer in marine palaeontology.

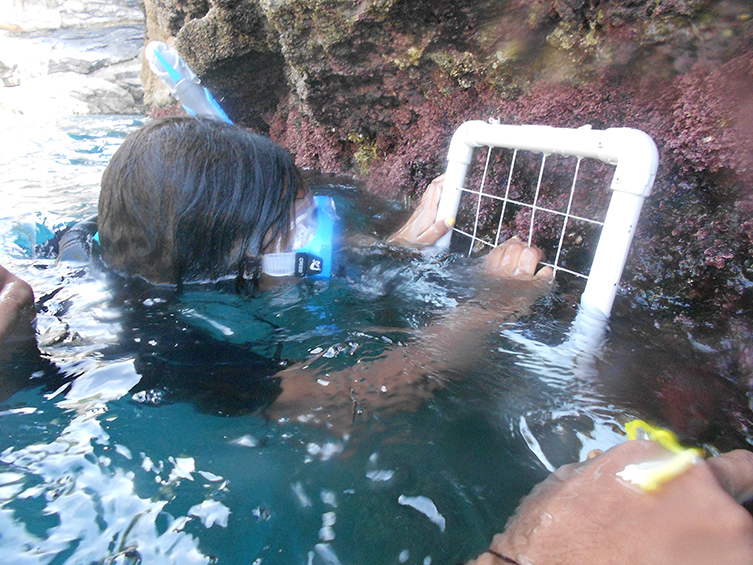

Leanne studies the effect of climate change on seaweeds and algae. Image ©Leanne Melbourne.

Seaweed and algae, found all over the UK, are an important part of the food chain. Without them, our oceans wouldn't stay healthy.

Leanne studies coralline algae, a group of red algae that produce calcium carbonate within their cell walls, which gives them a hard, chalky appearance. Coralline algae are important habitat formers. Some are known to support commercially farmed species of scallops.

However, climate change is affecting their ability to maintain habitats - if their unique structures are affected, it could have a big impact on the UK's marine food chain.

Leanne hopes her work will help to protect these important habitats in the future. But when she was at school in north London, Leanne never dreamed she'd become a scientist.

She says, 'I enjoyed science at school but never thought that this would be a career path. My parents are both from Jamaica and encouraged me towards medicine as a stable career path. I didn't think scientific research was even an option.

'I ended up doing a chemistry undergraduate degree and I realised then that I was interested in the natural environment. I gravitated towards studying ocean chemistry and its impact on biological organisms from there.'

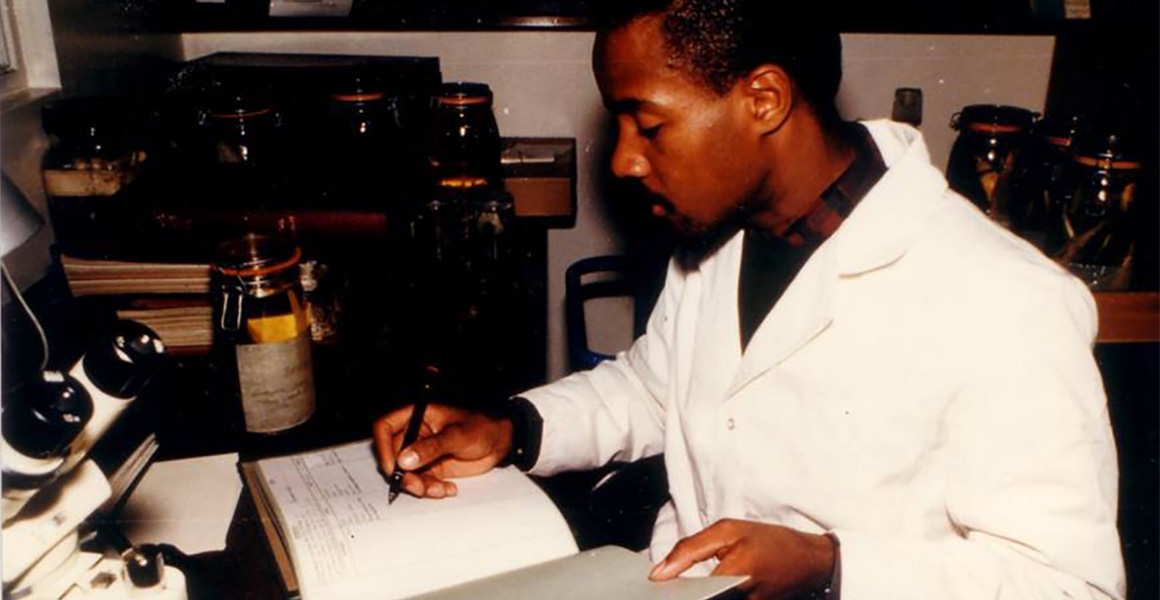

Leanne did her PhD at the University of Bristol and worked with the Museum's seaweed expert, Prof Juliet Brodie. She examined how climate change was affecting algae all over the UK.

Now she lectures students in Bristol and enjoys visiting schools to encourage youngsters to consider science as a career path.

'As I progress further into my career, I notice there are fewer women and fewer people of colour working at my level. I want everyone to feel that science is for them,' says Leanne.

'I love visiting schools and especially talking to young girls about my job. Sometimes you can see the penny drop when they see me and realise that science is an option for them. They may not have seen scientists who looked like them before.'

Leanne says she loves encouraging young women to pursue a career in science

The importance of coralline algae

Calcifying habitat formers such as coralline algae are just as important as coral reefs along our UK shores.

Coralline algae can be split into three groups: tree-like structures called articulated corallines, others that live on pebbles and rocks, and completely unattached forms that are called maërl or rhodoliths.

'Maërl are found all over the world, and the UK shelf has some of the most extensive mäerl beds in Europe,' says Leanne.

'Maërl interlock together and form extensive beds that support high levels of biodiversity; the spaces created in the lattice are ideal homes to a wide variety of organisms.'

'They are known to be nursery grounds to commercial species of scallops, so are of economic importance, but maërl are ecologically fragile and climate change is seen as a potential stressor. Much previous research on the effects of climate change on coralline algae has focused on photosynthesis and calcification. More recently researchers have realised the importance of analysing how their structural integrity is affected.

'Maërl beds are formed through fragmentation. A bit of maërl will break off, start to grow and eventually become a fully formed maëerl bed.

'Why is it important to analyse this? Changing the 3D structure will change the bed itself which will affect the organisms that inhabit it.'

It's never been more important to understand the health of our oceans. Here, Leanne is studying algae in Italy.

Leanne's research: the uncertain future of coralline algae

Rising carbon dioxide concentrations are causing the planet to warm up. As the planet warms so do our oceans, the UK sea surface temperatures have risen by 0.2 to 0.6 °C since the 1980s.

Another effect of this increasing carbon dioxide is it reacts with water, changing the chemistry of the ocean and lowering the pH. This is called ocean acidification, and it has led to a global decrease in the pH of 0.1 units since the pre-industrial era.

Leanne's research looked into how ocean warming and acidification affected the coralline algae. She says, 'My research showed that the colder temperate species from Scotland formed stronger skeletons than the warmer temperate species from Falmouth in the south of England.

'So in Scotland, where the temperatures are colder, growth is much slower and they are able to deposit more calcium carbonate, resulting in thicker cell walls and a stronger structural integrity. This highlights species specific responses and that we may see some species doing better than others.

'Surprisingly, when comparing the same species from different time periods (100 years apart), there were no substantial changes in the structural integrity. Other studies have shown that if the algae are left in stressful conditions for a longer period of time, their growth rate slows and the cell walls thicken, returning to a more normal level. They have the ability to acclimate to their surroundings, if the rate of change is slow enough- so there may be some hope.'

However, it isn't just ocean warming and ocean acidification that we need to think about. Increased sedimentation can threaten these organisms, as warmer, wetter winters lead to silt running off into rivers and estuaries, which can smother and suffocate the maërl.

Predictions of more frequent and intense storms in the oceans is also bad news for mobile organisms such as maërl. Increasingly stormier conditions will lead to more frequent collisions leading to smaller maërl fragments.

Leanne says, 'So even if these organisms are able to withstand increasing temperatures and corrosive waters, they will also have to face other less obvious pressures like increased sedimentation and stormier seas. These may have drastic consequences for the calcifying habitat formers found along our UK shores. Changes to these algal species can fundamentally change the nature of the beds they form, with consequences for the organisms that call these maëerl beds home.'

●Some text and facts included in this article are reproduced with the kind permission of the Linnean Society of London, and were originally published in PuLSe issue 39, Sept 2018; text © The Linnean Society of London.

Protecting our planet

We're working towards a future where both people and the planet thrive.

Hear from scientists studying human impact and change in the natural world.

More information

- Find out more about Leanne's current research at the University of Bristol.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media