A special collection of butterfly specimens at the Museum helps tell a tale of extraordinary adventure and scientific insight.

In 1848, the bank of the Amazon River was not where you'd expect to find an apprentice stocking-maker from Leicester.

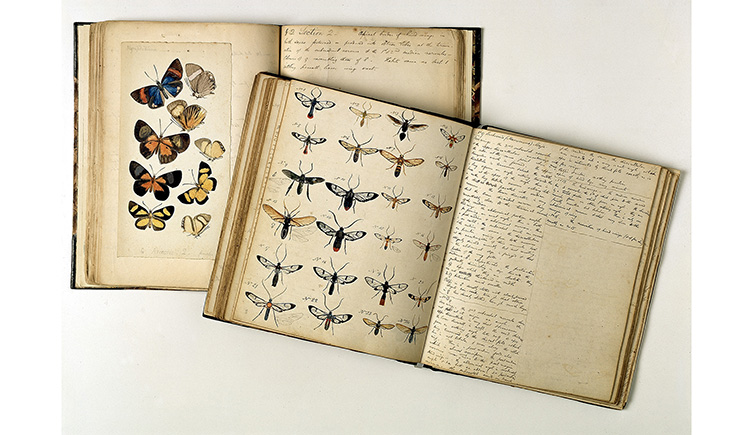

Colourful Asterope butterflies, many collected by Henry Walter Bates during his time in Brazil in the mid-1800s

A special collection of butterfly specimens at the Museum helps tell a tale of extraordinary adventure and scientific insight.

In 1848, the bank of the Amazon River was not where you'd expect to find an apprentice stocking-maker from Leicester.

Self-taught British entomologist Henry Walter Bates spent 11 years collecting butterflies in the Amazon in Brazil.

He braved all kinds of perils from wildlife, weather and disease. Because he spent much of his time along the river, disease-carrying mosquitoes and many other wild animals - including caimans, snakes and piranhas - would have been frequent companions. He fought flooding rains and dangerous currents, and succumbed to both yellow fever and malaria.

Dr Blanca Huertas, Senior Curator of Butterflies at the Museum, explains how Bates's fascination with insects helped a well-grounded theory on the evolution of species take flight.

Henry Walter Bates (1825-1892) was the eldest son of a stocking-maker in Leicester and left school at 13 to apprentice in the family trade.

A childhood hobby of collecting insects and an appetite for adventure would come to define his career.

In his early twenties, Bates met by chance a man named Alfred Russel Wallace in the local library. Fourteen years later, Wallace would co-publish with Charles Darwin the theory of evolution by natural selection.

At the time, Wallace was a teacher with a keen interest in botany, but time spent with Bates soon encouraged a shared fascination with beetles.

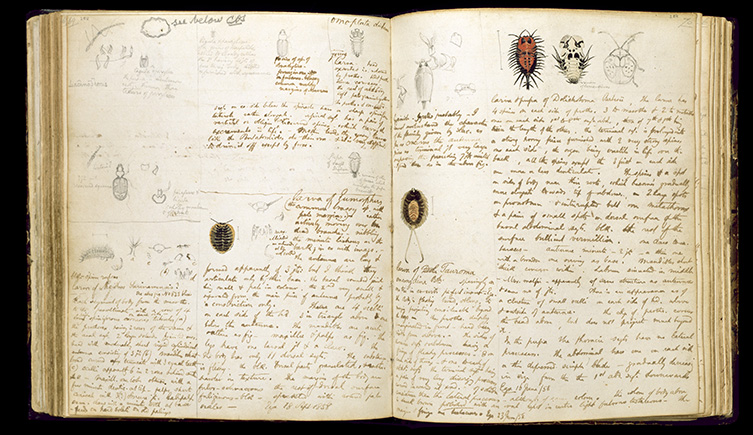

Bates's field journal showing details of insects he found on the Amazon

The pair became fast friends, collecting together in the Leicester countryside and dreaming of adventures in the tropics.

'I can just picture the pair of them exploring their local forests, discussing accounts of Charles Darwin's voyage on the Beagle and Alexander von Humboldt's journeys in South America,' says Blanca. 'They would have been tempted by all the marvels being discovered in the New World. It was a real time of adventure and opportunity, even for a boy with no formal training but with a great passion and interest in nature.'

In the autumn of 1847, Wallace, who wished to investigate how species evolve, proposed an expedition with Bates to explore the wildlife of the Amazon River in Brazil.

Bates was 23 years old when he left home, bound for the adventure of a lifetime.

Bates and Wallace arrived in Brazil in 1848 and together travelled parts of the Pará and Tocantins rivers.

However, the two friends went their separate ways that same year, with Wallace ascending the Rio Negro (towards Colombia) and Bates travelling deeper into the Amazon.

Wallace stayed in the Amazon for another four years before moving on to the Malay Archipelago. But Bates's fascination with the variety of insect life would keep him in the region for more than 11 years.

He was certainly in his element. This description from a paper Bates wrote in 1864 paints a clear picture of the abundance of butterflies he encountered:

'In some places, during the fine season (August to October), they assemble by hundreds, sometimes thirty or forty species together, of the most varied shapes and colours, to sport about in muddy places exposed to the morning sun. Callicore and Asterope, with liveries of velvet crimson and black, or sapphire and orange; Eunica, with purple hues glancing in the sunlight as they fly; swallow-tailed Marpesia of many species; silky-green Dynamine; blue, white and black Baeotus, tailed like the Charaxes jasius of Europe, and many other kinds less conspicuous in colour and form, are all seen together, either settled on the ground or swiftly flying to and fro above it.'

During his time in the Amazon he collected everything from botanical specimens to bird skins and snail shells, in addition to beetles, butterflies and moths.

Bright male and brown female butterflies (Nessaea obrinus) from the Amazon, collected by Bates in Pará and Ega (now called Tefé) regions

While the transport of material between Brazil and London was hazardous, it could be accomplished relatively quickly - at the time, the ocean voyage took less than seven weeks. Negotiating the Amazon was a very different matter, however. A round trip from the coast up the river to São Paulo de Olivença and back again entailed a seven-month voyage.

Bates kept meticulous records of his travels in pocket books, recording not so much where he was going, but what he saw.

'We have two of his unpublished field diaries here in the Museum's entomology library,' Blanca says.

Written in pencil or Indian ink in tiny script, Bates's logbooks include daily details of weather, rainfall, mean temperatures, descriptions of the wildlife he encountered and thousands of detailed pencil sketches and watercolours.

Bates's field journals are filled with meticulous sketches and watercolours. Many of the specimens illustrated here are in the Museum collection.

'His journals and letters home show the immense amount of taxonomic knowledge that Bates possessed and also allow us to clearly picture him at work, deep in the jungle surrounded by his ever growing reference collections and cages of various drying specimens,' says Blanca.

'It's astonishing what he was able to accomplish - especially when his precious new discoveries were at perpetual risk of being damaged by humidity, by transit or by being eaten by local wildlife.'

One letter home describes some of the creative solutions he developed to deter pests. Bates would hang specimens to dry on cords painted with bitter vegetable oils and invert a cuya (a locally made gourd bowl) to try to keep rats and mice from nibbling the drying animal skins.

Highly methodical in all things, Bates kept to a strict routine of collecting during the morning and reading, mounting and preparing his finds in the afternoon. He was typically in bed by nine.

Bates was able to secure ongoing funding for his work by feeding London's growing appetite for curiosities from the Neotropics. While maintaining a reference collection for his research, he sold the majority of his finds through auctions and to specialised natural history shops in London.

'Many collectors interested in showcasing the novel specimens from the New World acquired some of Bates's specimens,' says Blanca.

Bates was a prodigious collector. It is estimated that he collected more than 14,000 different insect species, 8,000 of them previously unknown to science or labelled as new species. He was so prolific that the curators at the British Museum who also took care of natural history specimens at the time didn't believe it was possible that he found so many new species - much to Bates's annoyance.

He wrote in a letter in 1863, 'On Monday morning I fell into a nest of hornets at [the] British Museum, in the shape of a knot of the leading curators […] criticising fiercely my statement of having found 8,000 new species out of 14,700.'

Blanca says, 'Today the Natural History Museum has the largest collection of Bates's butterflies in the world, including the types - the first-ever collected specimens of those many new species he discovered.'

Dr Blanca Huertas, Senior Curator of Butterflies, holds a drawer containing butterfly species of the genus Asterope - some of Bates's favourites - including specimens he collected in the 1850s. Some of the species have been named after Bates in recognition of his discoveries in the Amazon.

Without the assistance of local guides and inhabitants, Bates would never have been able to survive in the remote and uninhabited areas of the vast Amazon rainforest and make the discoveries that he did. He learned several native languages, customs and hunting methods, and had a number of close friendships with local inhabitants.

'We have tendency to tell the stories of British explorers as if they did it all on their own, but many - including Bates - had a great deal of help from local companions. They helped Bates find, identify and navigate the Amazon wilderness. It is important to remember them in the histories of science too,' says Blanca.

Henry Walter Bates is best known for contributing to the theory of evolution through his study of mimicry. Years of examining butterflies in the rainforests of Brazil allowed him to notice the way that otherwise vulnerable butterflies were in fact protected from predators, by copying the physical appearance of unpalatable or toxic species which predators had learned to avoid.

Blanca explains, 'Bates closely studied Heliconius butterflies for his discovery of mimicry. He was puzzled by the way a butterfly could move so slowly without being eaten by birds. He eventually discovered that it was toxic, it had a particular smell to it and birds had learned to avoid its bitter taste.'

In 1862 Bates published a scientific paper describing his ideas about mimicry. He believed harmless edible species occasionally produced forms with similar colour patterns to unpalatable toxic species. He believed these forms would be less likely to be attacked by predators, and would therefore pass on the same colouration to their offspring.

Males and females of the mimetic butterfly Ithomia flora and its mimic Dismorphia theucarilla

Without Bates's theory of mimicry it would have been difficult for Darwin to persuade his readers that the idea of evolution was valid or that it operated by natural selection. Mimicry was seen as one of the strongest demonstrations of evolution by natural selection, in this case brought about through the actions of butterfly predators such as birds, dragonflies or lizards.

'Today there are hundreds of known mimetic butterfly species from tropical forests, and scientists continue to build on the research begun by Bates. Today it is very exciting to see these early ideas being bolstered by modern science such as genetics, of which Bates and Darwin had no inkling at the time.'

Bates's chain of 'transitional' Heliconius butterflies collected during his trips to the Amazon, which illustrate how biological populations can evolve to become distinct species. Top left to bottom right: Heliconius melpomene, H. melpomene thelxiope, H. melpomene melpomene (hybrid) lucia, H. elimaea, H. erythraea, H. tyche, H. melpomene melpomene (hybrid) hippolyte, H. melpomene meriana.

Bates survived both yellow fever and malaria during his time in South America. His deteriorating health eventually led him to return to Britain.

Bates spent the next three years writing an account of his explorations, titled The Naturalist on the River Amazons, one of the finest reports of natural history travels.

'When you think about the rules of fieldwork, he was a pioneer. Bates literally wrote the book. When we go out to the field, we always hope to make great observations and discoveries - not only new species, but theories as Bates did,' Blanca says.

The Museum’s Lepidoptera collection contains approximately 8,712,000 specimens in 80,000 drawers.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media