Solving the puzzle of why penguins never stay soggy for long could help researchers develop the ultimate waterproof fabric.

Penguins looking dapper © Petra Christen/ Shutterstock.com

If you’re a fan of nature documentaries you’ve probably seen plenty of penguins on film. Standing proudly, as if they’re dressed for a black-tie event, the characterful birds are known for waddling comically on land and diving gracefully underwater.

One thing you won’t have seen is a penguin that stays wet for long. The birds are the proud owners of one of the best waterproof jackets in nature, allowing them to emerge from the sea and instantly dry so they don’t catch their death of cold.

This impressive adaptation is the latest to be investigated by Museum researchers working in the booming field of biomimetics, which uses nature’s evolutionary solutions to inform human technology and engineering projects.

Penguins need to dry off quickly after underwater dives to prevent hypothermia © Andrew S Williams/ Shutterstock.com

Prof Andrew Parker, who leads the research at the Museum, says that he had to adjust his initial thoughts around penguins’ waterproofing.

'It was always thought that they hold onto a layer of air, called a plastron, next to their skin,' he explains.

But the Museum team, in collaboration with researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Boston, USA, found that this isn't always the case. Some penguins dive down as far as 83 metres and they can't hold on to this layer beyond a few metres due to increasing water pressure.

Fear of water

Instead, their survival hinges on a very different strategy.

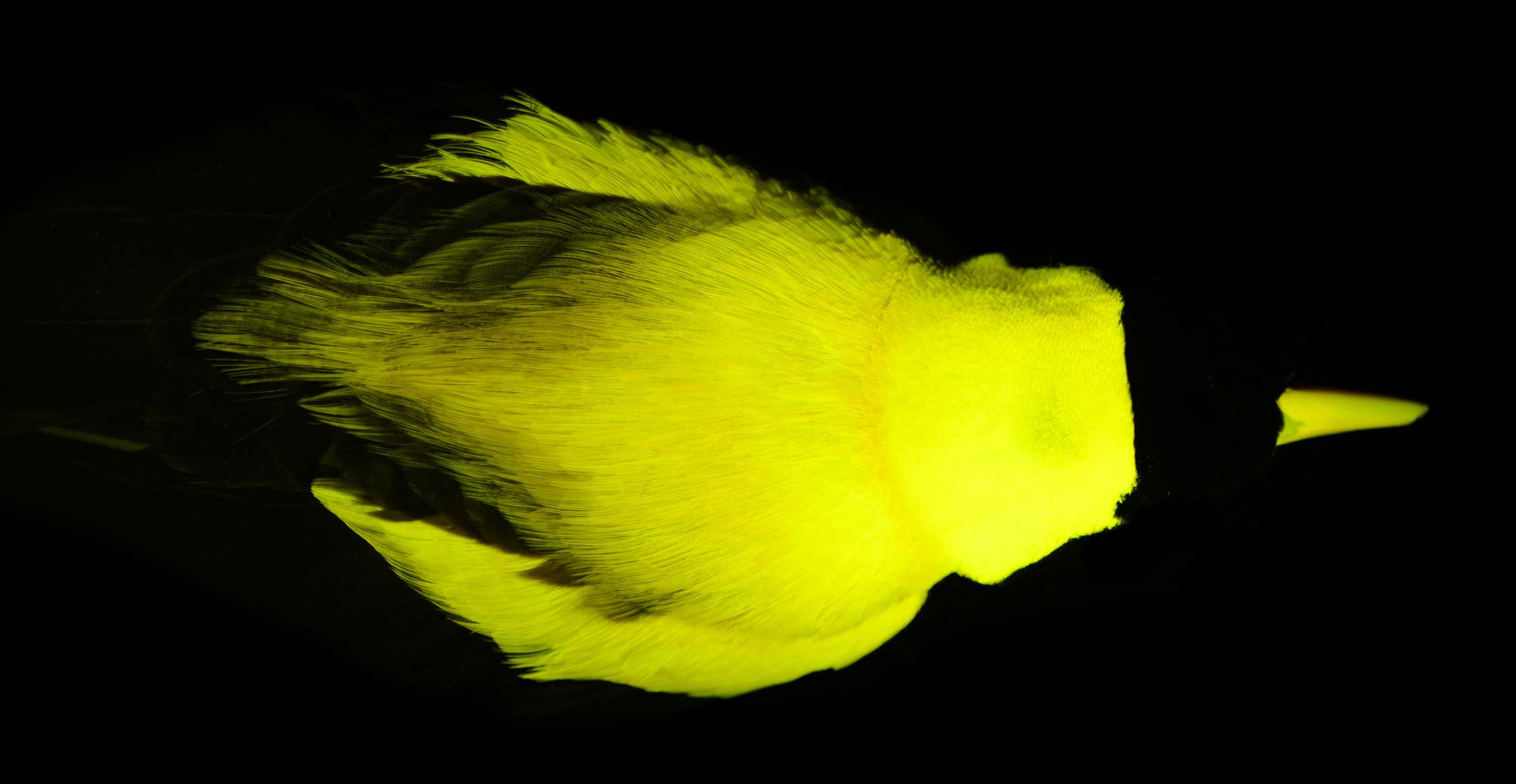

Water is forced away from the birds’ bodies immediately on their return to land so they can warm up rapidly, further research on individual feathers revealed. Scientists set about investigating what lay behind this trick, known as a superhydrophobic effect, and how it could be used to create fabrics for human use.

The penguin drawers in the Museum at Tring

Prof Parker’s team have been analysing the feather structures of preserved birds in the Museum’s collection, focussing particularly on penguin specimens. They have also been looking at the water-resistant feathers of auks, another family of diving birds that includes puffins and guillemots.

The team are analysing electron microscope images to investigate the miniscule architecture of the animals’ unique adaptations on the micro and even nano scale. Prof Parker is excited about what the electron microscope images could reveal, but he explains that the research involves more than just getting incredibly close to feathers.

He is currently asking zoos to collaborate on 'squeeze a penguin' experiments. This isn’t simply a challenge to hug one of the animals but to obtain preen oil, the substance the birds produce to coat their feathers. The team want to understand how the oil combines with the feathers' microscopic structures to create such effective waterproofing.

Feather of a diving bird, showing how its superhydrophobic nature causes water to ball up

After analysing the feathers under the electron microscope, Museum scientists have a good idea of the microstructures responsible for repelling water. They have been carrying out trials on materials that mimic these structures with their colleagues at MIT, and initial results look positive.

But they need access to a particularly precious specimen to advance their research. And that specimen is the great auk.

Extinct enigma

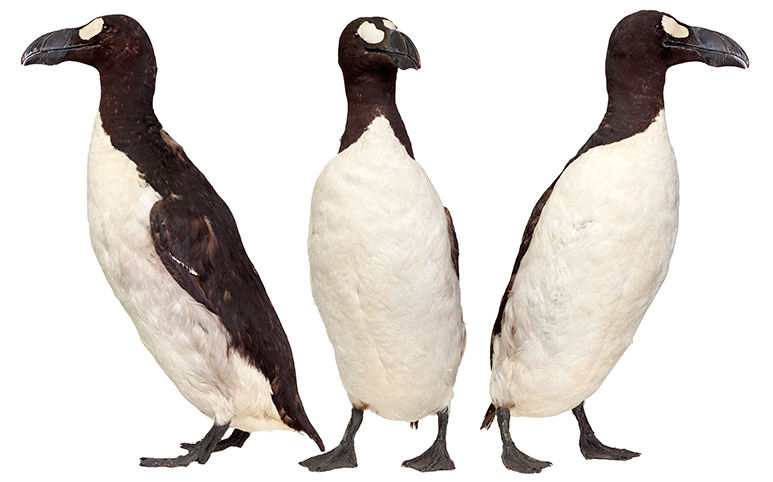

The great auk was once found on remote islands off eastern Canada, Greenland, Iceland and Scotland, but was hunted for its meat, eggs, feathers and oil. The species was finally declared extinct in 1850 and all that remains of it today are preserved specimens in museums, including four at the Natural History Museum.

What makes the species so important to Prof Parker’s research is that, unlike other members of the auk family, the great auk was flightless. While the microstructures of other auk feathers may be adapted for aerodynamics as well as repelling water, the theory is that the great auk’s feathers are not, so researchers should be able to isolate the waterproofing structures.

The great auk, an emblem of exploitation

If the great auk’s feather microstructures are similar to those of the penguins, Prof Parker says confidently that this would be the template to use to produce waterproof materials.

Such examples of convergent evolution, where unrelated groups of organisms find the same solution to a problem, are key to biomimetics. These adaptations are the result of nature’s rigorous trial and error testing over millenia. If the same result emerges independently in unrelated species, then that's a great endorsement of its effectiveness.

Tracing the trail

Prof Parker is fascinated by the process of evolution, and how the roots of the remarkable microstructures around today can be traced back millions of years.

’I believe it all ties back to the Big Bang of evolution - the Cambrian explosion - because that’s when all the different groups of animals started making their hard parts, independently and simultaneously,’ the professor says, describing the world-shattering period about 520 million years ago. 'They use the same mechanisms today as they did all that time ago.'

Understanding the origin and development of these adaptations could provide all-important short cuts to solving modern-day engineering problems, and help reduce the environmental impact on current factory processes.

While penguins may move a little awkwardly on dry land, the nature of their suits mean they are always well turned out after a dive.

Revealing the birds’ waterproofing secrets could lead us to some serious technological advances. And the ultimate waterproof fabric.

Bird collections

Find out about our bird collections. Housed in the Museum at Tring, they are among the largest in the world.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media