Oil on canvas portrait of John James Audubon, arguably the most famous American bird artist, painted by Lance Calkin sometime between 1859 and 1936.

Source: Natural History Museum, London, Library and Archives

John James Audubon: creator of The Birds of America book

Jay Sullivan

First published 20 January 2022

John James Audubon was a self-taught ornithologist and artist. The Birds of America, Audubon's collection of lifelike drawings, was a feat of artistry, technical skill and determination.

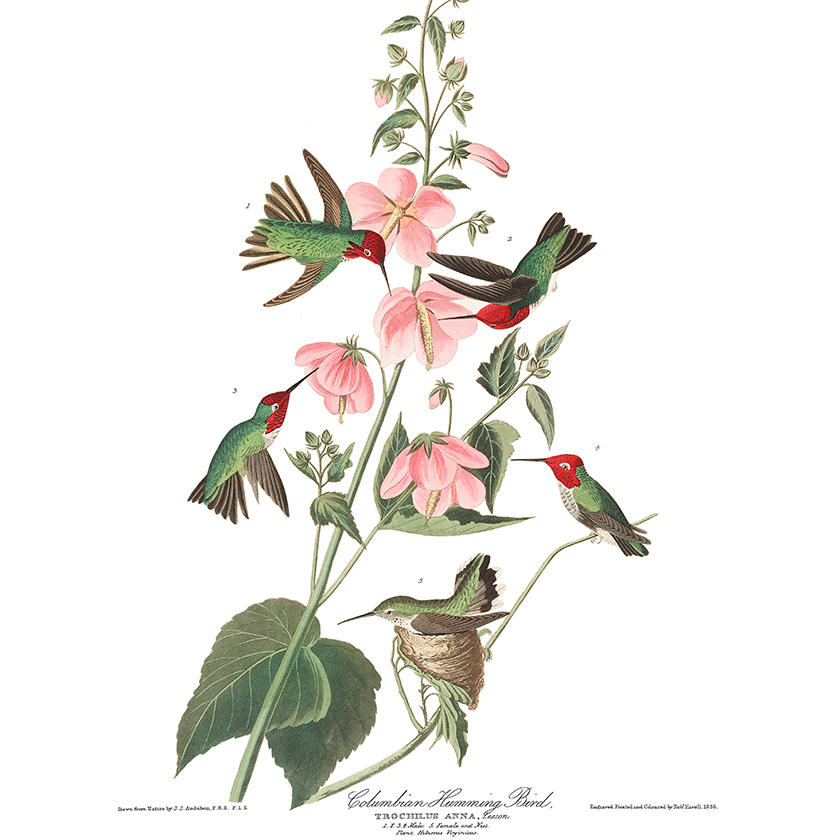

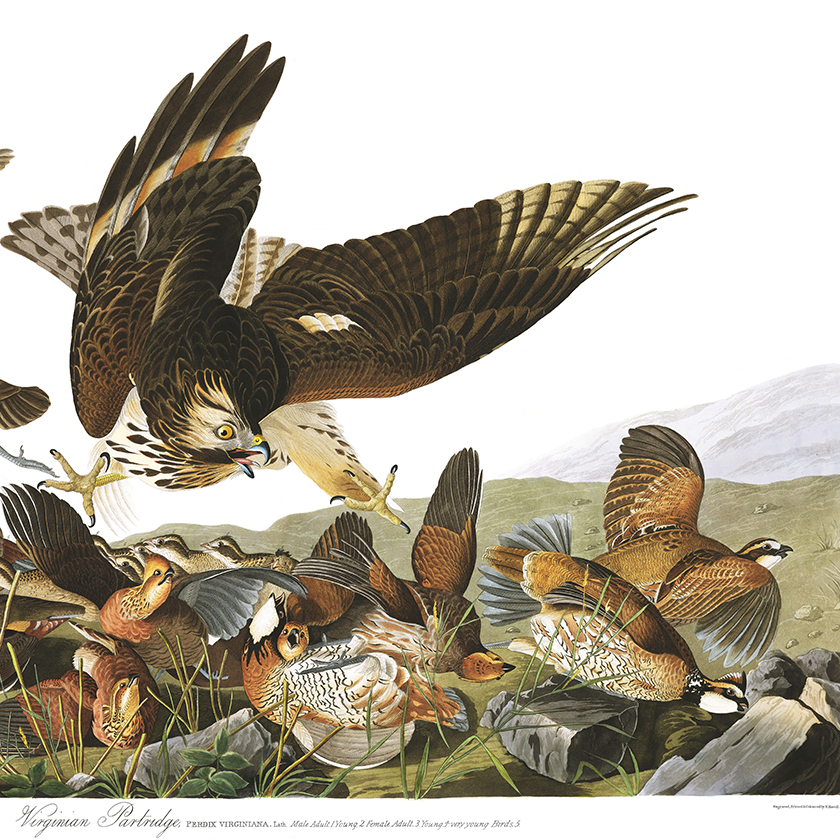

Its 435 engraved plates, published between 1827 and 1838, broke the mould of bird illustration by realistically depicting birds at life-size proportions and in animated poses, using innovative printing techniques.

Who was John James Audubon?

John James Audubon was born in Haiti (then known as Saint-Domingue) in 1785. His father would bring home birds and flowers which Audubon would observe first-hand, sparking his interest in natural history. Aged 11, he got his first taste of travel when he worked as a cabin boy on a navy ship.

Audubon was sent to the USA aged 18 to avoid conscription in the Napoleonic Wars. He took up residence at the farm his father owned in Pennsylvania. Here he met Lucy Bakewell, the daughter of a wealthy English couple, and they married in 1808. Lucy was highly educated and taught Audubon to speak English. During their courtship Audubon continued to draw birds and refined his methods by hunting them and rearranging the specimens with wire to give a more lifelike appearance.

The newly wedded couple moved to Kentucky where Audubon opened a chain of stores which eventually failed. Audubon preferred birds to day-to-day business, and several ventures such as a steam mill and a short stint as a taxidermist and artist for the Western Museum in Cincinnati did not bring success.

With his interest in birds never waning, Audubon decided that he would combine his artistic and ornithological talents and compile the first complete study of North America's bird species: The Birds of America.

Red-necked grebe (Podiceps grisegena), a print of one of John James Audubon's bird drawings that was incorporated into The Birds of America book.

Source: Natural History Museum, London, Library and Archives

What was John James Audubon famous for?

Audubon's detailed bird studies are what eventually brought him fame. They became his obsession, and he travelled widely across the country for many years to achieve his ambition.

To collect and draw bird specimens, Audubon lived a nomadic existence, moving back and forth across North America to record birds for his book.

Alongside his drawings, Audubon began writing a series of episodes about his experiences exploring the American frontier. They eventually became the book Ornithological Biography, or an Account of the Habits of the Birds of the United States of America (1831-1839).

Presented as autobiographical, these stories allowed Audubon to create a fictionalised version of himself as an all-American woodsman struggling to survive in the wilderness. Stories include hunting wolves and bears, becoming trapped in the snow and sleeping in a self-made igloo as well as an encounter with an escaped enslaved family.

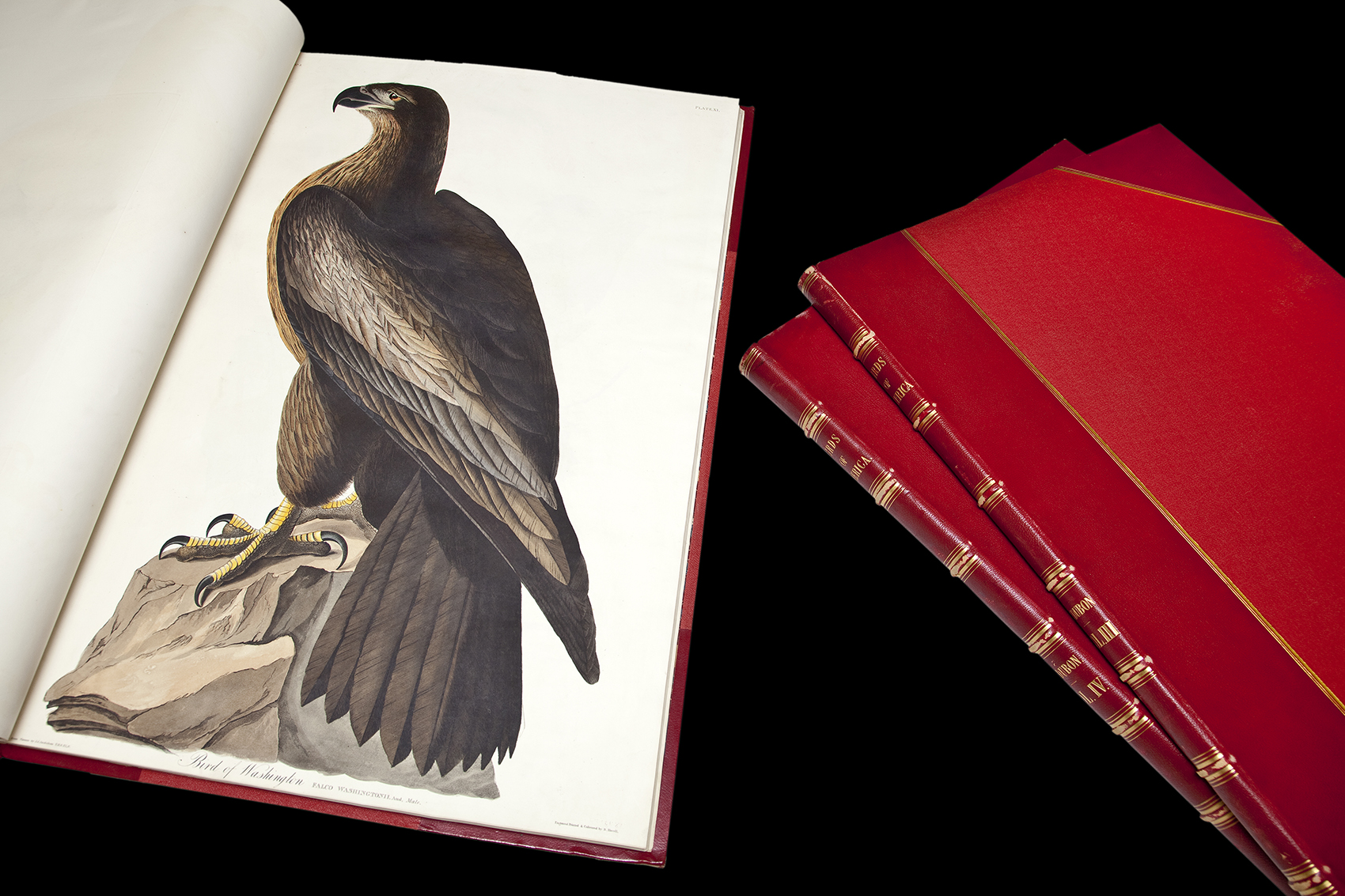

Audubon's words evoke the romance and violence of the wilderness. But the truthfulness of Audubon's writings has been subject to much debate and we now know that some tales are falsehoods. For example, Audubon claimed to have discovered a new species of eagle which he named the Bird of Washington, or Falco washingtonii. However, no concrete evidence has been found to suggest the existence of this animal.

Bird of Washington painting by John James Audubon. The existence of this bird is doubted.

Source: Natural History Museum, London, Library and Archives

Audubon in England

Despite his growing reputation as a talented artist and naturalist, Audubon was unable to find a publisher for what would become The Birds of America. In May 1826, he travelled to England in the hope of finding a suitable backer.

In November of the same year, engraver William Home Lizars offered to publish the first instalments of The Birds of America. However, unhappy with the standard of the engravings and frustrated by delays due to a printer strike, Audubon switched to Robert Havell Jr.

During this time Audubon raised funds by hiring city halls across the UK to display his drawings and charging admission. With a publisher secured and printing underway, Audubon returned to the USA in 1829.

A bound Museum copy of The Birds of America by John James Audubon. Today, The Birds of America book is very expensive because it is very rare - fewer than 120 copies survive.

Source: Natural History Museum, London, Library and Archives

The Birds of America book

The work John James Audubon is famous for was not his own idea. Scottish-American naturalist Alexander Wilson was already working on American Ornithology, a nine-volume set of books containing illustrations of North American birds. Audubon believed his drawings to be superior in quality and more comprehensive than Wilson's and hoped The Birds of America would surpass American Ornithology.

The Birds of America took ten years to complete. Audubon hadn't even finished identifying birds, let alone drawing them, when subscriptions began. Subscribers could expect each volume to have five illustrations: one big, one medium and three small.

While the idea of subscription seems unusual today, this was a common way to consume print in the Victorian era. Novels were often published in monthly instalments over several years before being published in full. This allowed the author to raise funds to support their work and buy them time to plot their novel. Time to raise funds was important to Audubon as The Birds of America cost around £100,000 to produce in total - equal to £1.5 million today.

Published between 1827 and 1838, the 435 prints transformed natural history illustration. Audubon used realistic perspective and backgrounds to capture the bird's appearance and behaviours. Determined to represent their real size, he depicted some large birds in contorted poses to fit them onto the piece of paper.

Several birds in The Birds of America are now extinct, including the passenger pigeon and Carolina parakeet. Audubon expressed concern about many species during his lifetime, fearing the impact of hunting and habitat destruction. He also named at least 25 bird species new to Western science, although many of these would have already been known to Indigenous People. Audubon was helped by many people, including African Americans and Indigenous Americans, who were often unacknowledged but provided him with information and support.

Another of John James Audubon's bird illustrations. This one shows the Carolina parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis), which was declared extinct in 1939.

Natural History Museum, Library and Archives

Audubon the slave owner

Audubon was a contradictory figure. He hunted birds yet was critical of other hunters. Despite a love of wildlife, he preferred to work with freshly dead specimens and often shot birds to do so.

Even during his lifetime Audubon had critics. Recently, more attention has been paid to Audubon's unacceptable views. He owned enslaved people, did not see Black people as equals and dismissed the movement to abolish slavery. There are also questions over the accuracy of his writing and the extent to which he falsified information to enhance his reputation.

Scientists and organisations connected with him are now looking to address these criticisms, including acknowledging his involvement in slavery.

Final years

The completion of The Birds of America did not quash Audubon's desire to travel and he continued to explore North America into his final years, until failing eyesight eventually forced him to stop travelling. John James Audubon died in January 1851 from complications due to dementia. His wife Lucy outlived him by 23 years and died aged 86.

Audubon's legacy

Audubon's book The Birds of America is an extraordinary and unprecedented achievement in the study of birds and printmaking, with a unique blend of science and artistry on a scale that has never been repeated. A window into the history of the academic study of nature, it continues to inspire artists, bird experts and conservationists alike.

The large size and high production cost of The Birds of America ensured its rarity. Of around 200 copies originally produced, just 119 are known to have survived to the present day. Many copies were taken apart and sold as individual prints.

The Museum has two editions in its collection, including a bound copy which belonged to Lord Rothschild, who founded the Natural History Museum at Tring.

The Birds of America is one of the most valuable books ever published: in 2018 a copy was sold at auction for $9.6 million.

John James Audubon's bird art captured the natural behaviour of species and depicted them life-sized. Here, Columbian hummingbirds (now known as Anna's hummingbird Calypte anna) are gathering nectar.

Source: Natural History Museum, London, Library and Archives

Many of Audubon's bird paintings featured in The Birds of America book show species in animated poses, such as these Virginia partridges (now known as Northern bobwhite Colinus virginianus) under attack from an eagle.

Source: Natural History Museum, London, Library and Archives

What is the Audubon Society?

Audubon's love of birds has led to several conservation societies being founded in his name, notably the Audubon Naturalist Society (ANS) and the National Audubon Society.

In 2021, these societies reassessed their association with Audubon, with the Audubon Naturalist Society choosing to change their name.

Lisa Alexander, Executive Director of ANS, stated:

'The deliberate and thoughtful decision to change our name is part of our ongoing commitment to creating a larger and more diverse community of people who treasure the natural world and work to preserve it. It has become clear that this will never be fully possible with the current name.'

The National Audubon Society has chosen to keep its name, but has published an article acknowledging Audubon's ethical failings and racist views.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media