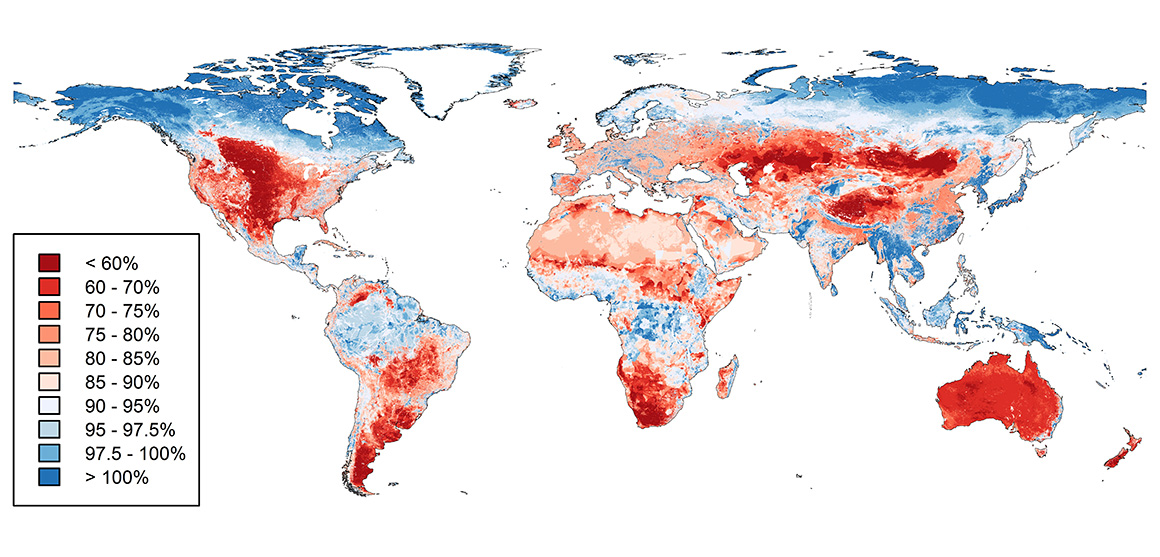

The loss of species diversity has reached unsafe levels across 58% of the world's land surface, according to a new assessment led by Museum scientists.

The research, published in the journal Scienceopens in a new window, found that human land use has driven down the population of many species to a dangerous extent across vast swathes of the planet.

Worryingly, biodiversity 'hotspots' - areas that are the only home for large numbers of species, and with high levels of habitat loss - are among the regions badly affected. Twenty-two of the 34 hotspots suffer from unsafe levels of biodiversity loss. Other areas that have suffered big losses include grasslands and savannahs.

'Across most of the world, biodiversity loss is no longer within the safe limit suggested by ecologists,' says the paper's lead author, Dr Tim Newbold of University College London and the UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre.

As a result, he adds, 'we are approaching a situation where human intervention may be needed to sustain the function of these ecosystems.'

Many biodiversity 'hotspots', such as the Succulent Karoo region of western Namibia and South Africa, are threatened by species and population loss. Photoopens in a new window by Wikimedia Commons user Winfried Bruenken, licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.5opens in a new window.

Ecological roulette

The assessment, conducted by Natural History Museum researchers and colleagues from across the UK, Europe and Australia, is one of the first to estimate biodiversity loss from ecological communities at a global scale.

To do this, rather than look at the numbers of species already lost to extinction, the team assessed the effect that habitat loss has had on populations of surviving species. This is an important measure of how well local ecosystems can continue to provide the goods and services on which people depend. It also tells researchers what scope remains for conservation.

The team found that grasslands, savannahs and shrublands were most affected by biodiversity loss, followed closely by many of the world's forests and woodlands. In these areas, the local ecosystems are facing an uncertain future as the level of biodiversity becomes increasingly unable to support them.

'For ecosystems to thrive, they need a variety of native species with adequate populations,' explains Museum researcher Prof Andy Purvis, who led the research team. 'It ensures the ecosystem still works even in a hot year - or a cold year, or a wet year - or if there is some kind of extreme event, such as a wildfire.'

Experts have therefore proposed using biodiversity loss alongside other measures of environmental change, such as carbon dioxide emissions and groundwater use, as a way to assess the effect humanity has on the planet.

Crossing the safe limits on these criteria means a potentially dangerous level of risk to the stability of the environment, similar to the effect that rising CO2 emissions have on the climate and that CFC emissions had on the ozone layer.

'This makes it extremely worrying that we've already pushed biodiversity below the proposed safe limit,' adds Professor Purvis.

'Until and unless we can bring biodiversity back up, we're playing ecological roulette.'

Human changes to land use, such as deforestation for palm oil plantations, are a driver of biodiversity loss. Photoopens in a new window by Wikimedia Commons user Achmad Rabin Taim, licensed under CC-BY 2.0opens in a new window.

Consequences for humans

Overall, the team found that across 58.1% of the world's land surface, the level of biodiversity loss is substantial enough to threaten the ability of ecosystems to support human societies. Together these areas are home to 71.4% of the global population.

'Decision-makers worry a lot about economic recessions, but an ecological recession could have even worse consequences,' says Professor Purvis.

The paper points to pollination as one example of a vital ecosystem function that could be under threat. With 35% of global food production in some way dependent on animal pollinationopens in a new window, a loss of pollinators could mean lower crop yields and less food worldwide.

A loss of diversity among pollinators could affect crop production worldwide © Ratikova/Shutterstock.com

Data deluge

Tracking biodiversity requires a huge amount of data: in total, the team analysed almost 2.4 million records covering more than 39,000 species. This information was collected by over 500 researchers worldwide and shared via the PREDICTS database of global diversity.

The information was then used to calculate how biodiversity in every square kilometre of land has changed since pre-industrial times.

Although the results were stark, the team hopes that they will help inform conservation policy, both nationally and internationally.

To that end, the researchers are making the maps and data from their paper publicly available.

'This is a vitally important area of research,' explains Prof Purvis, 'which is why we'll be releasing our data on the Museum's Data Portal, so anyone can use it in their own models.

'The better we understand the problem of biodiversity loss, the more chance we have of tackling it.'

More information

- Read the scientific paper in the journal Scienceopens in a new window.

- Find out more about biodiversity research at the Museum.

- Access the Museum's Data Portal.

Protecting our planet

We're working towards a future where both people and the planet thrive.

Hear from scientists studying human impact and change in the natural world.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media