A new lunar meteorite has joined the Museum's collection. The sample, weighing 147 grammes, will help researchers' studies into the origin and early evolution of the Moon.

Prof Sara Russell, Merit Researcher in the Division of Mineral and Planetary Sciences, says the acquisition comes at a very exciting time for lunar research.

She says, 'Both the European Space Agency and NASA have plans to put humans on the Moon, and maybe even a human base. To do that we need to know what resources might be available.

'We need to know whether there is water that can be extracted from the rocks, for example, and what minerals might be there.'

The Museum's collection includes a slice of the Dar al Gani 400 lunar meteorite, which was found in the Sahara desert in 1998

From the Moon to the Museum

Lunar meteorites are rare finds. When an asteroid strikes the surface of the Moon, rocks are launched into space and some eventually fall to Earth.

Meteorites are often found in deserts, says Prof Russell, as the dry conditions mean they don't weather away.

She says, 'Deserts are much better places to look for meteorites than temperate regions like London. If it fell here at the Museum in South Kensington, then it would get rained on and disintegrate within a few years. But in the Sahara, for example, they survive much longer.'

The new specimen, NWA 11444, is so named because it was found in northwest Africa. It was purchased by the Museum from a British meteorite collector.

A piece of the Moon brought back by Apollo 16 astronauts on display in the Earth Hall at the Museum. This specimen is kindly loaned by the Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science Division at the NASA Johnson Space Centre.

Why is it interesting?

Studying rocks not only helps scientists understand the composition of the Moon, it also gives us clues about how the early solar system evolved, including the Earth.

It is thought that both Earth and the Moon received their water from meteorite bombardment, which was much greater in the early days of the solar system. Although the Moon subsequently lost most of its water, some remains locked up in its soil and rocks.

To study lunar geology, many scientists analyse the rocks and soils collected by astronauts during the six missions of the Apollo program which landed on the Moon between 1969 and 1972.

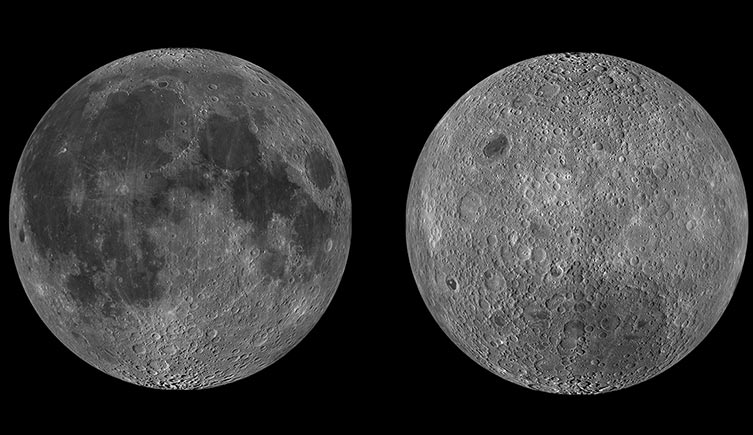

However, all the Apollo samples were collected from a similar region, close to the equator and on the near side of the Moon.

'Lunar meteorites are really exciting as they give us a better idea of the global diversity and composition of the Moon,' explains Prof Russell. 'They can come from any part: the poles, the equator, the far side or the near side.'

The far side of the Moon (right), unseen from Earth, looks very different from the near side (left)

Return to the Moon

Interest in the Moon waned after the Apollo program finished, but now a new generation of space missions are planning to return.

While NASA and the European Space Agency are drawing up plans, the China National Space Administration will likely be first back on the surface.

They are planning a robotic mission that will sample soil and rocks and return them to Earth. The Chang'e 5 mission aims to land a spacecraft on the Moon by 2019.

The Moon could make an excellent staging post for further exploration of our solar system, either with a manned base or used as a fuelling station. Finding accessible water would be a huge boost for such plans - water can be used for drinking or growing plants, or processed to make both hydrogen fuel and oxygen.

A piece of Moon rock collected on the last Apollo mission and given to the UK, on display in the Museum's permanent Treasures exhibition

New Museum exhibition

The specimen will now be available for both Museum staff and external researchers to study.

'As well as its research value,' adds Prof Russell, 'it's also brilliant timing because the Museum is planning a meteorites exhibition that's going to open in the autumn of 2018. We hope that this lunar meteorite can feature in the exhibit.'

Related information

- Visit the Museum's research pages on the Moon

- Take a look at some of our stories on space

Space: Could Life Exist Beyond Earth?

Find out in our latest exhibition! Snap a selfie with a piece of Mars, touch a fragment of the Moon and lay your hands on a meteorite older than our planet.

Open now

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media