Birds are, by some estimates, the most diverse group of vertebrate animals living on land today.

New research shows how this seemingly large variety in birds' skull shapes is just a tiny fraction of the diversity seen in their dinosaur ancestors.

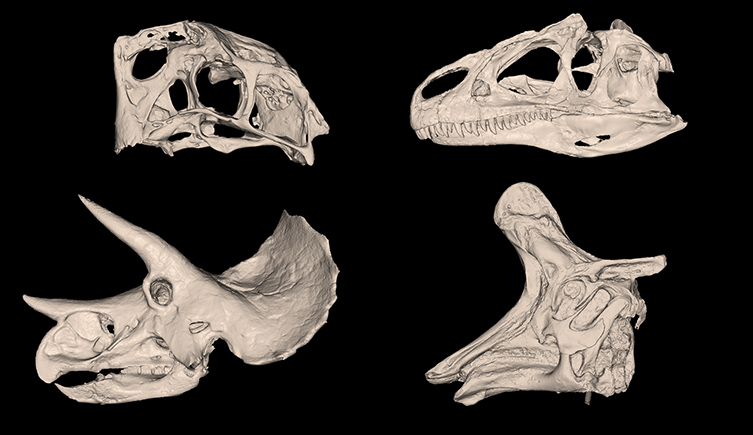

Birds are just highly specialised dinosaurs, as shown by this Tyrannosaurus rex skull compared to that of a greylag goose (not to scale) © Ryan Felice

Birds are, by some estimates, the most diverse group of vertebrate animals living on land today.

New research shows how this seemingly large variety in birds' skull shapes is just a tiny fraction of the diversity seen in their dinosaur ancestors.

There are more than 10,000 species of birds living all over the world, varying from huge plant eaters to tiny nectar drinkers. Birds have a massive range of habitats, lifestyles, body sizes and beak shapes.

Birds are directly related to the dinosaurs. They are the only surviving lineage of dinosaurs that managed to escape the destructive impact of an asteroid that hit Earth 66 million years ago.

To date, no studies have looked at how this variation in birds, and particularly their skulls, compares to that of the dinosaurs that went extinct.

Ryan Felice, a scientific associate at the Museum, has been 3D-scanning dinosaur and bird skulls to compare their shapes, and see exactly how evolution has worked on these two groups. His paper is published in PLOS Biology.

It was the variation in beak shapes of finches that helped Darwin develop his theory of evolution through natural selection © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

'Normally we think about birds as being this very impressive diversification, we think there must be something special about birds which allowed them to evolve into the many species that we see today,' says Ryan.

'But it actually seems like their skulls evolved more slowly than all the other dinosaurs.'

This means that while we think of birds today as being mega-diverse, they actually represent just a fraction of their dinosaur ancestors' variation.

It is often easy to forget that birds have a direct link to the mighty Diplodocus and fearsome Tyrannosaurus rex.

These highly specialised dinosaurs, or birds, are frequently used as an example of what is known as an adaptive radiation. This is the process in which an organism or group of organisms rapidly diversify in shape to take advantage of different environments. It is often seen when a group of once dominant animals go extinct, such as when all the non-avian dinosaurs died off.

It is thought that when the dinosaurs went extinct the Earth was emptied of species, allowing the surviving birds to fill the roles that many of their extinct relatives once occupied. Through this process they became all the wonderful and weird varieties we now see.

But this huge explosion of bird species has never been studied in the context of wider dinosaur evolution. We think of birds as having had this rapid diversification, but how does it actually compare to that of their now-extinct relatives?

Extinct dinosaurs show a huge variety in the shapes of their skulls, but birds are limited by their highly specialised morphology © Ryan Felice

Ryan and his colleagues have scanned over 380 birds and dinosaur skulls and used a new method to capture the shape of the skull. They trackedin incredible detail how the bones have changed over the last 200 million years.

'There was a huge range of skull shapes and ecologies across all dinosaurs, and then almost everything went extinct,' explains Ryan. 'All that were left were this one group of dinosaurs that were very specialised with no teeth: the birds.

'All of the diversity that has come since is just building on that one type of dinosaur that survived and so they are locked into that very specific specialisation.'

The results show that birds are just a small slice of the once huge array of dinosaurs.. This can be seen when you consider just how dramatic the difference in skulls is between some of the most iconic species of these extinct animals, from Triceratops with its spiralling horns, to T. rex and its bone crushing jaws or the duck-billed hadrosaurs with their bizarre teeth.

It also turns out that while it was thought that birds diversified pretty quickly once their dinosaur ancestors went extinct, in actual fact their evolution over the last 66 million years has been far slower than what was seen with the proceeding dinosaurs.

Dinosaur skulls have an incredible variety in shape and size as shown by the skulls of Citipati osmolskae (top left), Allosaurus fragilis (top right), Tricerotops horridus (bottom left) and Lambeosaurus lambei (bottom right), not to scale © Ryan Felice

'Birds turned out to be just a really tiny proportion of dinosaur variation despite the fact that they are the most diverse vertebrates on land today,' says Prof Anjali Goswami, the senior author of the paper. 'They are nothing compared with what they used to be.

'Birds show lots of amazing bursts of innovation after the other dinosaurs wentextinct, but when it comes to their skulls, it really seems like evolution hit the brake pedal when birds originated, compared to their dinosaur ancestors.'

This is likely because they were already highly specialised when the asteroid hit. Once they had the opportunity to diversify, their skulls were in effect already locked into a specialised shape, in which they fed using beaks and had proportionally big brains.

'It's a massive bottleneck in dinosaur evolution,' explains Anjali. 'While birds are incredibly diverse in lots of ways, they do it all through plumage and colour and behaviour, but they don't do it through the bony parts of their skull.'

This paper forms one part of a major project in Prof Goswami’s group, using a new scanning and analysis technique that allows the comparison of seemingly completely different skulls. The overall aim of the project is to scan and compare the skulls across all land vertebrates to see just what role evolution has played in their shapes.

Find out what science is revealing about how dinosaurs looked, lived and behaved.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media