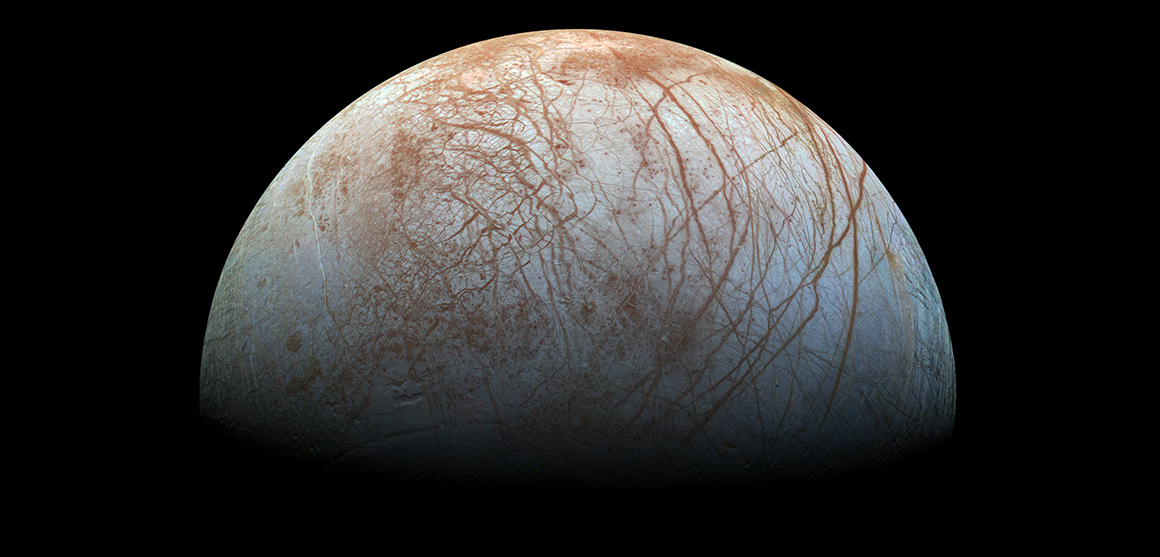

Phosphine gas has been found in the clouds of Venus that could have been created by microbes.

A computer-simulated image of the planet Venus, using images of the surface mapped by NASA's Magellan spacecraft. The colouration was based on images recorded by the Venera 13 and 14 spacecraft. © NASA/JPL

Scientists have detected phosphine on Venus. On Earth, this gas is created by microbes that live in oxygen-free environments. It means there is a chance that we've found signs of living organisms in the clouds of our neighbouring planet.

The temperature on the surface of Venus is exceptionally hot, and no life could survive there. But it is thought the planet was once cooler and wetter, with conditions that may have allowed life to start more easily.

Scientists found the phosphine gas in the acidic clouds floating above the planet. It is a harsh, windy environment, but the pressure there is similar to that of Earth's surface. The clouds also contain a zone where it is a comfortable temperature for life, so it has been suggested before that they could be a living habitat.

Researchers have been using telescopes to look for evidence of phosphine in Venus's clouds since 2016.

The findings are published today in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Prof Sara Seager, a planetary scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a co-author on the new study, was careful to emphasise that this is not yet conclusive proof of life.

She says, 'We are not claiming to have found life on Venus. We are claiming a confident detection of phosphine gas whose existence is a mystery.'

Volcanoes can produce phosphine, but only miniscule amounts - far less than the quantities detected by the scientists. They also ruled out things like lightening and meteorites.

Researchers are left with another possibility - that small organisms are responsible.

Sara says, 'We hope our work will motivate space mission that go to Venus and directly measure gasses in the atmosphere. People have speculated about life in Venus's atmosphere for decades.

'Perhaps life originated in the past when Venus was cooler, with liquid water oceans.

'As Venus heated up the oceans evaporated and the surface became so hot that any life would have been killed, but any life in the clouds would have survived.'

Earth has life in its clouds too, swept up from the surface. Bacteria live in the liquid water droplets, which are then rained back down on Earth.

Earth's clouds don't last long before they turn to rain, but on Venus the clouds are permanent. However, Venus's atmosphere is very harsh so it is difficult to directly compare it to Earth.

What is phosphine?

Phosphine is a toxic, colourless, smelly gas with an odour often likened to rotting fish and garlic.

On Earth, phosphine is produced by microbes, but we don't know for sure which organisms give it off. It is usually found in oxygen-free environments, where only certain types of bacteria survive.

Biologists don't yet know the exact biochemical path that produces the gas, even here on Earth.

Phosphine is considered to be a biosignature gas - a gas that is produced by life forms and accumulates in a planet's atmosphere.

It is found in the atmospheres of Jupiter and Saturn too, but it shouldn't exist on Venus because of the planet's chemical makeup.

Dr Louisa Preston, a UK Space Agency Aurora Research Fellow, is an astrobiologist based at the Museum. She says, 'It's exciting to think that our sister world, sitting right on the edge of the solar systems' habitable zone, could have conditions suitable for life.

'However as with all scientific discoveries in astrobiology we will need to look much more closely at the different ways phosphine can be created without life, to be able to conclusively say that this discovery is life. What this has done has really brought Venus back into everyone's minds after having taken a backseat to Mars for many years, and we can’t wait to see what secrets she is hiding.'

The study

This research was completed by an international team of astronomers, led by Professor Jane Greaves of Cardiff University.

They used the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) in Hawaii to detect the phosphine, and were then awarded time to follow up their discovery with 45 telescopes of the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile.

Both facilities observed Venus at a wavelength of about one millimetre, much longer than the human eye can see.

Prof Greaves told the Royal Astronomical Society, 'This was an experiment made out of pure curiosity, really – taking advantage of JCMT’s powerful technology, and thinking about future instruments. I thought we’d just be able to rule out extreme scenarios, like the clouds being stuffed full of organisms. When we got the first hints of phosphine in Venus’ spectrum, it was a shock.'

The team painstakingly measured levels of phosphine in the clouds, and ruled out any alternative reasons for its presence.

The team believes their discovery is significant because they can rule out many alternative ways to make phosphine, but they acknowledge that confirming the presence of life needs more study, and possibly a mission to our next-door planet.

Dr Anne Jungblut is a microbiologist at the Museum studying life in extreme environments.

She commented, 'The finding of a compound such as phosphine that is associated with microbial life on Earth is exciting news. It highlights the importance of studying microbes and their metabolisms in the environment as it might potentially provide information on the conditions that are required for life to produce the gas on Earth, and might help to find more clues on the origin of the gas on Venus.'

More information

This research was led by scientists based at Cardiff University, the University of Manchester, MIT, the University of Cambridge, Kyoto Sangyo University, Imperial College London and others.

No Museum researchers were involved in the study.

Space: Could Life Exist Beyond Earth?

Find out in our latest exhibition! Snap a selfie with a piece of Mars, touch a fragment of the Moon and lay your hands on a meteorite older than our planet.

Open now

Explore space

Discover more about the natural world beyond Earth's stratosphere.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media