The origins of a meteorite which lit up skies above the UK last year have been revealed.

Water and organic molecules are among the contents brought along by the Winchcombe meteorite during its nearly 300,000-year-long journey to Earth.

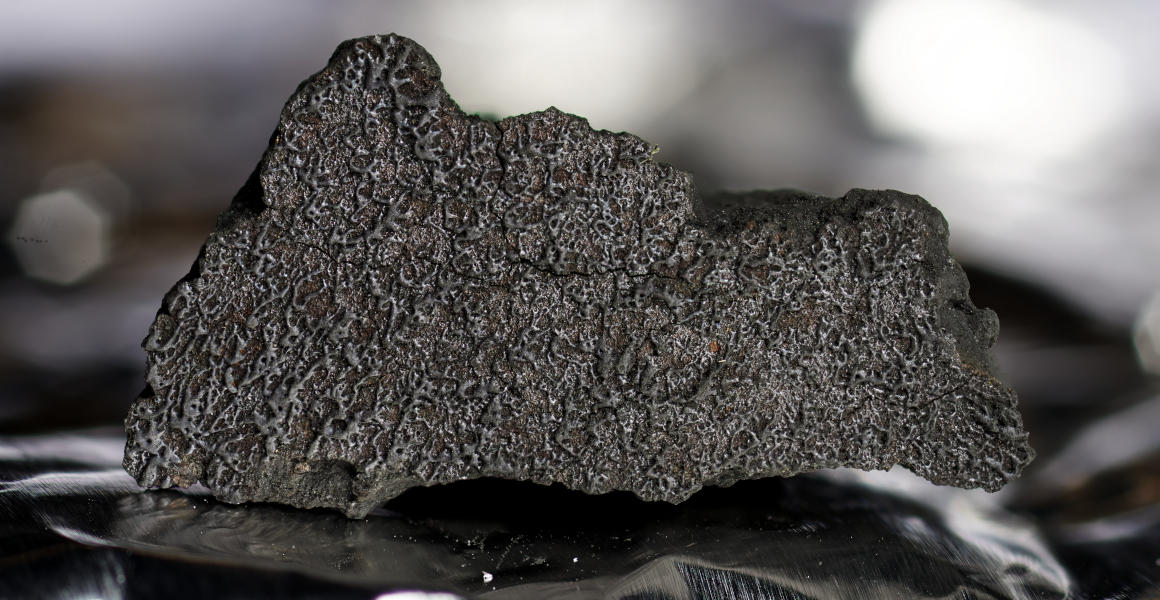

The Winchcombe meteorite is currently the only meteorite to have been seen falling in the UK in the past 30 years which has been recovered. Image © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London (All Rights Reserved)

The origins of a meteorite which lit up skies above the UK last year have been revealed.

Water and organic molecules are among the contents brought along by the Winchcombe meteorite during its nearly 300,000-year-long journey to Earth.

Extraterrestrial water and the building blocks of DNA are among the contents of a rare meteorite that landed in the UK last year.

The Winchcombe meteorite was the first of its type ever to be recovered in the UK when it struck the eponymous Gloucestershire town in 2021. Its rapid collection by members of the public and scientists ensured it was preserved in almost pristine condition, allowing researchers to investigate the materials it has carried from outer space.

A new study, published in the journal Science Advances, adds support to the suggestion that meteorites brought important molecules to Earth that helped to set the scene for life to evolve.

Dr Ashley King, who co-led the study and is an expert on meteorites at the Museum, says, 'The Winchcombe meteorite is incredibly well preserved, and has all the ingredients which can start to create a suitable environment for life to evolve are locked up inside it.'

'The composition of its water, based on the hydrogen isotopes, is very similar to what is seen in Earth's oceans, while amino acids, which are used to build DNA, are also found inside it.'

'We know it's not been contaminated, so this research adds weight to theories that carbonaceous asteroids were important in bringing these molecules to Earth after its formation.'

The Winchcombe meteorite was sealed into bags after being found, reducing its exposure to Earth's atmosphere. Image © NASA/JPL-Caltech, licensed under Public Domain via NASA Image Library.

While the Winchcombe meteorite may have fallen to Earth in Gloucestershire, its origins lie more than 300 million kilometres away. The number of cameras which caught the meteorite's fall to Earth have allowed scientists to trace its path back to its where it came from in the asteroid belt.

For millions of years the meteorite was part of a larger asteroid orbiting between Mars and Jupiter. It shows evidence of having been exposed to solar winds from the Sun, suggesting that it spent some of that time at the surface of the asteroid.

Less than 300,000 years ago, this would all change as a collision in the asteroid belt broke the rock apart and flung the meteorite into near-Earth space. At the time of its formation, it is estimated to have weighed around 30 kilograms, or the same as around six cats.

It rapidly ended up in orbit around 116 million kilometres from the Sun, which is around 300 times the distance between the Earth and the Moon.

'We found that it didn't pass particularly close to the Sun compared to other asteroids, and that it was only travelling for around 300,000 years or so which is really quick,' Ashley explains.

'However, as Winchcombe is a really fragile type of meteorite known as a carbonaceous chondrite, it won't make it to Earth if it doesn't arrive quickly, and will either fall into the Sun or break up.'

Winchcombe's orbit wasn't completely circular, meaning it was sometimes closer to the Sun and sometimes further away. At the very edge of its orbit, it was around the same distance the Earth is from the Sun and, on 28 February 2021, the two bodies finally came into contact.

Caught in Earth's gravity, the meteorite was pulled out of orbit and blazed across the sky as it fell to Earth. It travelled at around 13.5 kilometres per second as it fell, which is around 15 times faster than a rifle bullet but still the slowest speed recorded for any meteorite of its type.

Most of its mass was burnt away as it tore through the atmosphere, fragmenting it into pieces which fell across the town of Winchcombe and the surrounding area. Around half a kilogramme of meteorite was eventually recovered, which is close to the estimated mass of fragments which should have survived.

'We were lucky with Winchcombe in lots of ways,' Ashley adds. 'The UK should expect two to three small meteorite falls each year, but these often land somewhere inaccessible.'

'The fact that it fell on a very clear night, and in an area observed by cameras, allowed us to find it quickly. It was also a dry week, ensuring that it could be quickly packed away without being altered too much by Earth's atmosphere.'

The Winchcombe meteorite was sealed into bags after being found, reducing its exposure to Earth's atmosphere. Image © Mira Ihasz, Spire Global & The University of Glasgow

For the past 18 months since its collection, the Winchcombe meteorite has been subject to extensive testing to examine its chemical makeup. While carbonaceous chondrites are already a rare type of meteorite, it being collected so quickly has made it an even more important source of scientific evidence.

'The first material from the driveway was recovered within about 12 hours, which barring landing in my lap while I'm at the Museum is pretty much as quick as a meteorite will ever be recovered,' Ashley says. 'It gives us a pristine look at what its original composition was on the asteroid, with the first measurements of water taking place less than a week after it was recovered.'

Previous carbonaceous chondrites have had some similar readings to the Winchcombe meteorite's hydrogen makeup, but due to the length of time they were on the Earth scientists couldn't be sure how much they've been contaminated.

However, comparisons with samples taken of the materials used to handle the meteorite, as well as bits of the driveway and soil it landed on, have been used to rule out contamination of Winchcombe.

The majority of its mass is made up of phyllosilicates, clay-rich minerals that researchers studying Mars look for as they are promising candidates to preserve organic matter. While there's no evidence of life in Winchcombe, it does contain organic molecules such as lipids and fatty acids.

It also contains a variety of other materials including hydrocarbons, metals such as iron, titanium and aluminium, and trapped noble gases like neon.

Knowing what meteorites like Winchcombe contains allows researchers to research the asteroid belt without sending robotic probes to directly sample them. This can help inform our understanding of how the solar system formed.

'We only know where less than one percent of meteorites we have studied come from, so Winchcombe represents an important find,' Ashley adds. 'When we study meteorites with known origins, we can find out what the mineralogy and chemistry of their parent bodies are like.'

'This allows us to start mapping out the geology of the solar system.'

Find out in our latest exhibition! Snap a selfie with a piece of Mars, touch a fragment of the Moon and lay your hands on a meteorite older than our planet.

Open now

Discover more about the natural world beyond Earth's stratosphere.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media