The oldest disease-causing fungus on record has been found in the Natural History Museum’s collections.

Preserved in exquisite detail, the new species has been named in honour of author and fungi fan Beatrix Potter.

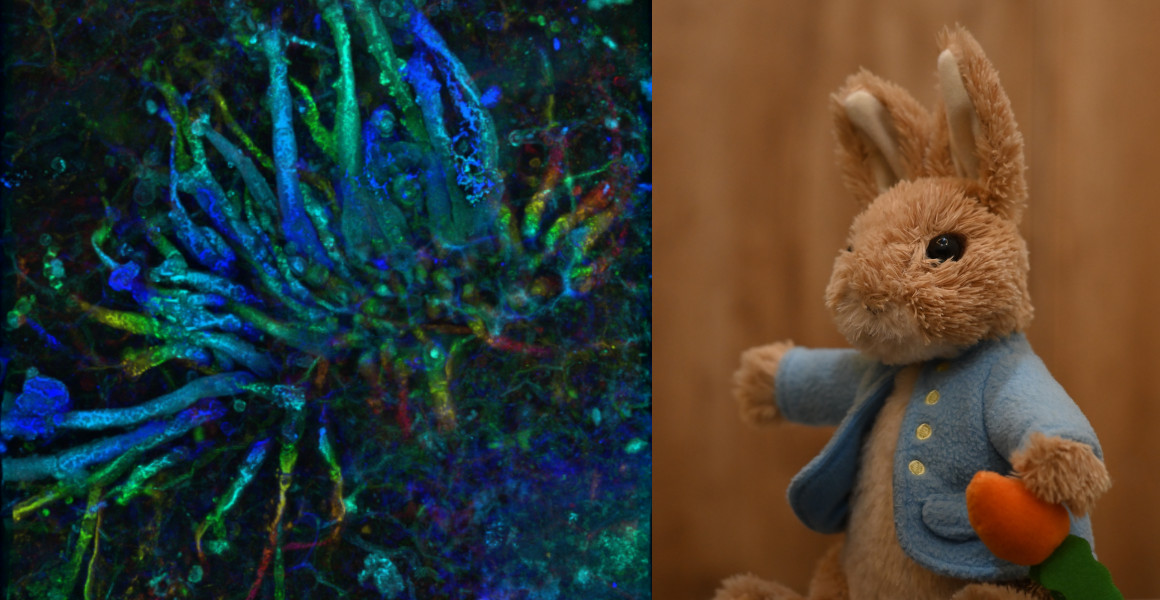

While Beatrix Potter may be most famous for Peter Rabbit (right), she is now famous among mycologists (fungi scientists) as the namesake of the earliest fungal pathogen (left). Fungi image © Christine Strullu-Derrien and toy image © Srivatsava369/Shutterstock.

The oldest disease-causing fungus on record has been found in the Natural History Museum’s collections.

Preserved in exquisite detail, the new species has been named in honour of author and fungi fan Beatrix Potter.

One of the UK’s most celebrated writers has been immortalised as a fossil fungus.

Found in the collections of the Natural History Museum, the new species Potteromyces asteroxylicola has been named in honour of Beatrix Potter. While she may be better known for books including The Tale of Peter Rabbit, Beatrix Potter was a noted lover of fungi in her lifetime.

Her detailed drawings of fungi, and study of their growth, were in some cases decades ahead of scientific research. This passion for fungi has now been recognised in Potteromyces, which is currently the earliest disease-causing fungus ever discovered.

Dr Christine Strullu-Derrien, the lead author of a study describing the new species, says, ‘Beatrix Potter’s work wasn’t recognised in her lifetime, but many mycologists now see her as a very important figure.’

‘I first had the idea to name a fungus after her a long time ago, so it’s a pleasure to finally be able to deliver on this and provide the appreciation from the scientific community that she didn’t get while she was alive.’

The findings of the study were published in the journal Nature Communications.

Beatrix Potter had a love of nature throughout her life, later breeding and farming sheep in the Lake District. Image © A D Harvey/Shutterstock.

Fungi are among the great unsung heroes of the natural world. In particular, they play a large role in cycling of nutrients that plants and other organisms depend on to survive.

Some species, for instance, live among the roots of plants in mycorrhizas where they help the plant take up minerals in return for sugars – a relationship known as a symbiosis. Other species are vital as decomposers, unlocking nutrients contained in dead plants and animals so they can return to the environment.

Not all fungi, however, are as beneficial. Many fungi can cause diseases in plants and animals, from the relatively harmless athlete’s foot through to conditions like chytridiomycosis, a condition which has decimated amphibian populations worldwide.

The new study suggests that all of these conditions have a historical precedent in Potteromyces. Christine and her fellow researchers found it in samples taken from the Rhynie Chert, a layer of rocks from Scotland which have been vital in understanding the early evolution of plants and associated fungi.

‘To find fungi, which are formed of such delicate structures, you need to find an environment where everything is preserved in good condition,’ Christine says.

‘The Rhynie Chert holds some of the best preserved fossils of early fungi, plants and arthropods anywhere in the world, and is especially important for capturing the moment when many species were starting to colonise the land.’

Using a confocal microscope, which uses 2D images of different parts of a sample to build up a 3D picture, the team were able to investigate slides from the chert in unprecedented detail.

They discovered that one slide at the Natural History Museum contained what looked like a new fungus. Its reproductive structures, known as conidiophores, had an unusual shape and formation unlike anything seen before.

However, because the appearance of fungi can differ so much between individuals the team had to find another specimen to prove it was a species in its own right.

‘Working on fossil fungi is not like working on dinosaurs,’ Christine says. ‘When you find a dinosaur, an individual can be described as a new species, but for fungi you have to find more than one to be really confident you have something unique.’

‘I found the first Potteromyces specimen in 2015, but it took years until I discovered another so that I could describe it.’

The second specimen was discovered in the collections of National Museums Scotland in another slide from the Rhynie Chert. With this, the team could now begin to investigate their new species in earnest.

What most excited the researchers studying Potteromyces was not just the fungus itself, but what it was found with. The fungus was found growing in an ancient plant called Asteroxylon mackiei, having burst in through its outer wall to kill the plant’s cells and absorb their nutrients.

In response, the plant had developed dome-shaped growths, showing that it must have been alive while the fungus was attacking. So far, this reaction to the fungus is unique in the Rhynie Chert.

‘While other fungal parasites have been described in the Rhynie Chert, this is the first to evidence one causing disease in a plant,’ Christine says. ‘It’s possible that there might be older disease-causing fungi, but we don’t have a good enough understanding of fungi from this time to prove this.’

The fossil record of fungi is notoriously difficult to study, as their soft, delicate bodies don’t lend themselves to fossilisation. Though some researchers claim to have discovered fungi that are as much as a billion years old, those reports have been questioned by other researchers.

Amid this debate, Potteromyces is providing valuable new evidence to piece together the history of fungi and help to clear up some of the confusion around the group’s origins.

‘The record of Ascomycota, the group Potteromyces belongs to, is particularly poor and it’s often controversial whether or not the fossils that do exist should be classed as ascomycetes,’ Christine says.

‘Potteromyces helps to change this. While it’s probably not a direct ancestor of any living fungus, it can provide a valuable point to date the evolution of different groups from.’

Christine believes that the Rhynie Chert still has much more to reveal and that, with enough time, it could help to solve the mystery of where the fungi we know today came from.

‘When I first started work on the Rhynie Chert, it was only meant to take two or three years,’ Christine says. ‘It’s now been 12, and I still think there is a lot to discover from his fabulous site.’

‘New technology is helping to uncover more information all the time, with investigations of its chemistry and other factors to find out about the site in unprecedented detail.’

We're working towards a future where both people and the planet thrive.

Hear from scientists studying human impact and change in the natural world.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media