Bumblebees develop new 'trends' in their behaviour by watching and learning from other members of the group.

New behaviours can spread rapidly through a colony even when alternative methods are discovered.

Research increasingly shows that watching and learning play a bigger role in bumblebee behaviour than previously thought. Image © Aliaksei Marozau/Shutterstock.

Bumblebees develop new 'trends' in their behaviour by watching and learning from other members of the group.

New behaviours can spread rapidly through a colony even when alternative methods are discovered.

Many complex behaviours displayed by bumblebees and other social insects are thought to be largely ingrained from birth.

However, research increasingly shows that learning by observation and imitation plays a bigger role in how some behaviours develop than previously thought.

A new study, led by Queen Mary University of London, set out to test social learning in buff-tailed bumblebees, Bombus terrestris.

Researchers trained a few individuals to open a puzzle box in which they received a sugar reward and found that this knowledge was then passed on to nearly all other members of the colony.

Furthermore, the bees continued using the same behaviour they had learned, even after discovering an alternate solution to the problem.

Scientists involved in this study believe this provides strong evidence that social learning has a more significant role than previously thought in the foraging behaviour of bumblebees.

Dr Alice Bridges, the lead author of the study from Queen Mary University of London, says, 'Bumblebees – and, indeed, invertebrates in general - aren't known to show culture-like phenomena in the wild.'

'However, in our experiments, we saw the spread and maintenance of a behavioural "trend" in groups of bumblebees – similar to what has been seen in primates and birds. The behavioural repertoires of social insects like these bumblebees are some of the most intricate on the planet, yet most of this is still thought to be instinctive.'

'Our research suggests that social learning may have had a greater influence on the evolution of this behaviour than previously imagined.'

Details of this study were published in the journal PLOS Biology.

Changes in bumblebee foraging behaviour might be due to experienced bees retiring and new learners arising. Image © weinkoetz/Shutterstock

Social insects, including bees, wasps, ants and termites, have evolved complex social behaviours, enabling individuals to work together cooperatively.

These communities or colonies tend to have one or a few females responsible for egg-laying. The rest usually comprises sterile individuals that carry out other tasks to benefit the group, such as gathering food, building and repairing the nest or hive, caring for eggs and larvae, and defending the colony.

Scientists have observed variations in many of these behaviours, not just in similar species but also among different communities of the same species.

Many of these specialisations are thought to have evolved through evolutionary trial and error and are preprogrammed into an organism at birth. But research is increasingly looking at the role that social learning plays in enabling these behaviours to emerge.

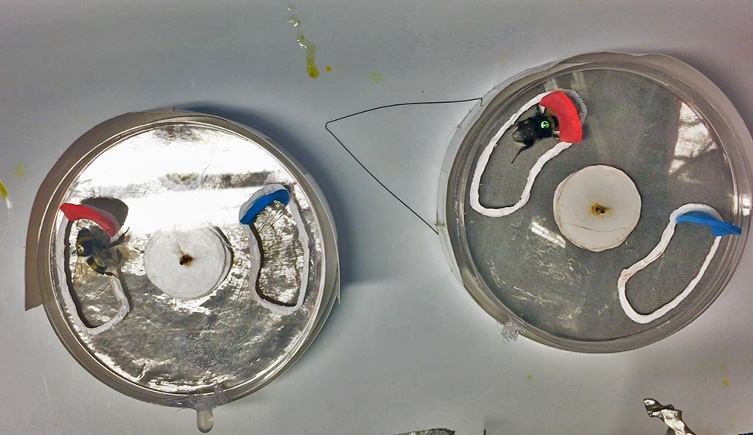

Researchers designed a puzzle box to see how learned behaviour spreads across bumblebee colonies. Image © Bridges AD et al., 2023, PLOS Biology.

The researchers designed a puzzle box with two possible solutions to see how learned behaviour develops within bumblebee colonies.

The bees could open the box by pushing a red tab clockwise or a blue tab counter clockwise.

Scientists trained 'demonstrator' bees to solve the puzzle using either the red or the blue tabs. When mixed with the rest of the group, the other bees, who had not been trained, overwhelmingly and consistently chose to use the same method they had observed from the trained bee, even after discovering the alternate option.

In comparison, control groups without a demonstrator bee opened the box fewer times, indicating that the bees were learning from others rather than figuring it out for themselves.

Other experiments involved releasing both 'blue' and 'red' demonstrators into the same population of bees. At first, the observers started to learn both methods, but within two weeks, the colony overwhelmingly chose one method over the other.

According to the researchers, this shows how behavioural trends might emerge within a population of bees. It also explains how changes in foraging behaviour might be due to experienced bees retiring and new learners arising rather than individuals changing their preferred behaviour.

Professor Lars Chittka, Professor of Sensory and Behavioural Ecology at Queen Mary University of London and an author of the study, said, 'The fact that bees can watch and learn, and then make a habit of that behaviour, adds to the ever-growing body of evidence that they are far smarter creatures than a lot of people give them credit for.'

'We tend to overlook the "alien civilisations" formed by bees, ants and wasps on our planet – because they are small-bodied and their societies and architectural constructions seem governed by instinct at first glance.'

'Our research shows, however, that new innovations can spread like social media memes through insect colonies, indicating that they can respond to wholly new environmental challenges much faster than by evolutionary changes, which would take many generations to manifest.'

Find out about the plants and animals that make the UK home.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media