The oldest colonial animal might actually be one of the oldest types of seaweed.

Debate over the fossil Protomelission's true identity is likely to continue until better preserved specimens are found.

The new specimens of Protomelission (left) measure as much as 16 centimetres long, and are substantially larger than the millimetre-sized originals. Image adapted from © Zhiliang Zhang, licensed under CC BY 4.0opens in a new window via Natureopens in a new window and Zhang Xiguang.

The oldest colonial animal might actually be one of the oldest types of seaweed.

Debate over the fossil Protomelission's true identity is likely to continue until better preserved specimens are found.

The origins of an ancient animal lineage are being called into question after new fossils were uncovered in China.

Back in 2021, Protomelission gatehousei was named the oldest bryozoan, a member of a group of colonial organisms made up of tiny animals known as zooids. The fossils were around 40 million years older than any previously discovered, dating it to the Cambrian period when other major animal groups are thought to have first evolved.

However, a new Nature paperopens in a new window suggests that Protomelission isn't a bryozoan after all. Using newly described specimens, the researchers argue that the species is actually a type of seaweed, suggesting that these algae might have been an important habitat for early animals.

Dr Martin Smithopens in a new window, a co-author of the paper from Durham University, says, 'This fossil is clearly not a normal bryozoan, and we've opened other possibilities for what it might be.'

'While it's difficult to be entirely conclusive, I think we have a pretty strong case that this is a dasyclad algae. The new specimens preserve soft parts of the organism such as tapering flanges, which don't fit the bill for suspension feeding bryozoans, but would be useful for photosynthesis.'

The reassessment of Protomelission is likely to meet resistance, however.

Dr Paul Taylor is a scientific associate at the Museum and was part of the team who named the species in 2021.

'In the two years since Protomelission was proposed as a bryozoan, this attribution has been universally accepted by bryozoan specialists,' Paul says. 'In my opinion, the new paper's arguments are insufficient to dismiss Protomelission as a Cambrian bryozoan.'

'They do, however, underline the inherent uncertainty in identifying fossils like these with simple morphologies.'

The new fossils were uncovered in China's Xiaoshiba Biota in the south of the country. Image © Yang Jie

The new specimens were found in southern China's Xiaoshiba Biotaopens in a new window, where Cambrian fossils are extremely well preserved. They are much larger than the original Protomelission fossils, which were just millimetres long, but share a number of striking similarities.

'My colleagues in China got in touch, and showed me a side by side comparison of both the Protomelission fossils and the specimens they had uncovered,' Martin says. 'This convinced me they were on to something.'

'The Cambrian is littered with microfossils so it's very rare to find something larger, and to be able to connect them together is even rarer still.'

The team argue that Protomelission makes an unlikely bryozoan, as it doesn't have the right characteristics. These include a lack of tentacles that bryozoans use to feed, as well as the gaps through which the tentacles stick out of the animal.

Instead, they think the species is actually the oldest known dasyclad algaeopens in a new window. Like bryozoans, these organisms are also thought to have evolved during the Cambrian, but sufficiently old specimens had not been found.

Not only do the new specimens suggest that dasyclad alage might have been present over 400 million years ago, they also show that their fossils might have been known about all along. There are some similarities with a group of microfossils known as cambroclaves, which are found all over the worldopens in a new window but whose origins are uncertain.

'The new specimens hint that the cambroclaves could be the remains of other dasyclad algae, and if so, it shows that seaweeds were not rare in the Cambrian after all,' Martin says. 'Instead, they could have had a wide distribution which we just haven't appreciated.'

'It could even be speculated that the diversification of seaweed could have contributed to the diversification of animals we see during the Cambrian.'

Some of the new fossils of Protomelission appear to be attached to a brachiopod shell. Image © Zhang Xiguang

This interpretation of Protomelission is yet to convince scientists in the bryozoan camp, however. There are doubts that the new specimens are the same species as the earlier finds, let alone an alga.

Part of the disagreement is a result of the way that the specimens are preserved. The original Protomelission specimens were formed as a result of phosphate replacing the organic skeleton after death, duplicating the structure of its tissues.

The newer specimens, meanwhile, are preserved as moulds left behind in rock after the skeleton has been lost. This can preserve parts of the internal and external structure of an organism, but the fossils are very compressed.

Paul argues that the new paper has misunderstood the process of preservation, which explains why some typically bryozoan features aren't present.

'As tentacles are exceedingly rare in fossil bryozoans preserving soft parts, their absence in association with the flanges is not at all surprising,' Paul explains. 'The incomplete phosphatisation of Protomelission can explain why regular apertures are lacking, given that the organic skeleton of bryozoans becomes thinner towards the aperture.'

'This allows them to open and close during life, but as a consequence they're less likely to survive in a fossil.'

He adds that the description of the flanges is also open to interpretation, and could also represent structures in bryozoans such as spines or tubular extensions around the apertures known as peristomes.

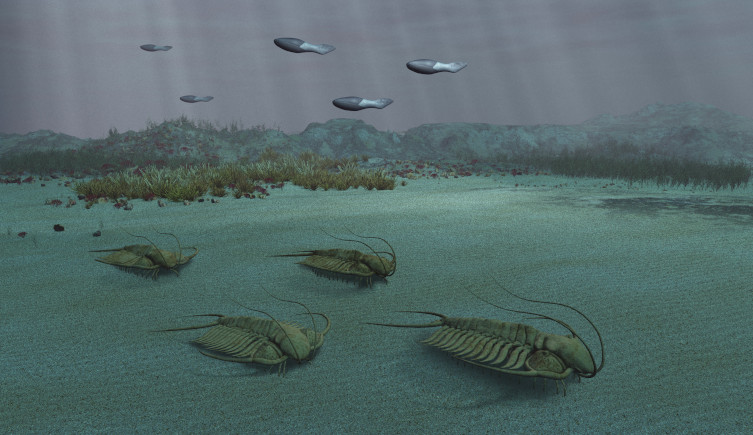

Groups of animals such as trilobites first evolved during the Cambrian. Image © Esteban De Armas/Shutterstock

Whether Protomelission is bryozoan or algal, and whatever the true identity of the new specimens, they remain important for studying the Cambrian period. As the point in time where almost all body plans and animal groups originated, it is a vital period to understand the evolution of life in its early years.

'These fossils allows us to think more about the process of evolution,' Martin says. 'Has it always been the same, or was it different during the Cambrian?'

He says that if Protomelission isn't a Bryozoan, and that they evolved after the Cambrian, then it adds weight to suggestions that evolution then wasn't significantly different from how it is today.

'We tend to think of the Cambrian explosion as a unique period in evolutionary history, in which all the blueprints of animal life were mapped out,' Martin says. 'Most subsequent evolution boils down to smaller-scale tinkering on these original body plans.'

'If bryozoans truly evolved after the Cambrian, it shows that evolution kept its creative touch after this critical period of innovation.'

On the other hand, if Protomelission is a bryozoan then understanding the Cambrian period is more important than ever. Both sides agree that more evidence is crucial, not just to understand this species but to reveal more about early evolution.

'More fossils preserving additional features, such as early growth stages, are needed,' Paul says. 'It's the only way to settle these questions.'

Find out more about why we need to protect the oceans, find themed events, and read about the pioneering work of the Museum's marine scientists.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media