Tiny teeth are revealing the roots of the modern mammal lifestyle.

While their ancestors grew at a near-constant rate, by 161 million years ago mammals had developed a quick burst of growth in their youth.

Dryolestes (left) and Haldanodon (right) are both Late Jurassic mammals, which had much higher growth rates than their earlier relatives. © James Brown

Tiny teeth are revealing the roots of the modern mammal lifestyle.

While their ancestors grew at a near-constant rate, by 161 million years ago mammals had developed a quick burst of growth in their youth.

While most modern mammals live fast and die young, their ancient relatives preferred to take life in the slow lane.

By studying the teeth of mammals from the start, middle and end of the Jurassic Period, scientists have seen how mammals transitioned from a distinctive group of reptile-like animals into the mammals we know today.

Crucial to this change was a shift in how mammals lived and grew. While a modern mouse might live for a couple of years at most, early mammals of a similar size might have survived for as long as 14 years.

The difference is thought to be due to modern mammals having much higher metabolisms than their ancestors. While this allows them to have more active lives than their predecessors, it causes higher rates of ageing that ultimately results in a shorter lifespan.

Dr Pam Gill, a Scientific Associate of the Natural History Museum and the University of Bristol, was co-lead author of the paper.

“This data suggests that while living small-bodied mammals are sexually mature within months from birth, the earliest mammals took several years to reach sexual maturity, corroborating recent findings for one of our studied animals, Krusatodon,” Pam says.

“It turns out that this long, drawn out life history was common amongst early mammals all the way through the Jurassic.”

Dr Elis Newham, postdoctoral research fellow at Queen Mary University of London and the first author of the study, adds that the Jurassic was “pivotal” in mammal evolution.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to reconstruct the growth patterns of these early mammals in such detail,” Elis says. “The results suggest that the unique life history traits of mammals, like high metabolic rates and extended parental care, evolved gradually over millions of years.”

The findings of the study were published in the journal Science Advances.

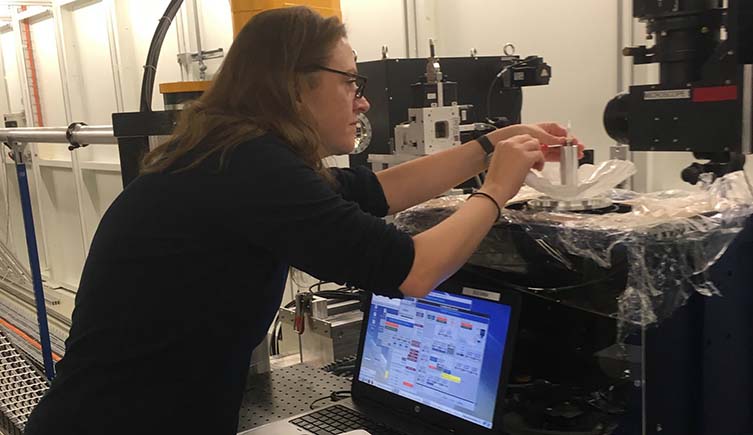

The team used a synchrotron, a device capable of generating high-intensity X-rays, to scan the teeth of a variety of living and extinct mammals. © Pam Gill

When it comes to investigating the history of mammals, scientists can always rely on teeth. Unlike the rest of the skeleton, they’re easy to fossilise and hard to break, as well as providing clues about an animal’s life history.

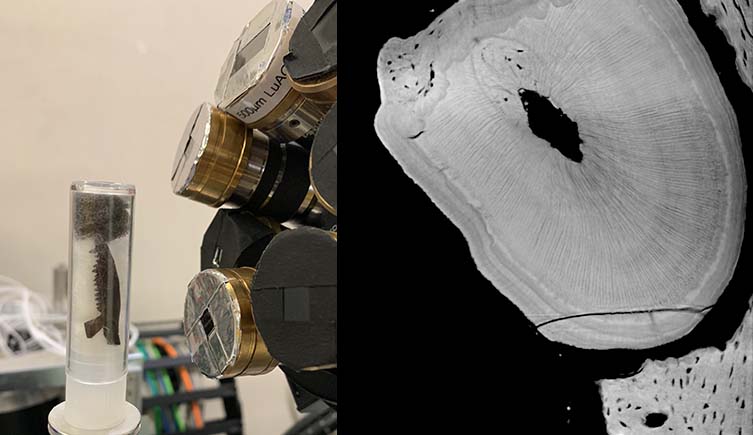

A substance known as cementum, which helps to anchor the tooth into the jaw, is particularly important for this. Cementum is deposited around the root, like rings on a tree, with each ring representing a year of life. The width of each ring is also related to how much an animal grew in a particular year.

However, just like trying to find out the age of the oldest trees, scientists face a problem. The 200-million-year-old teeth of the earliest mammals are rare, and until recently the only way to find out how old the animals were was to cut into them.

“While fields like forensics and archaeology might take thin sections of the teeth to age an individual, these precious fossil teeth are far too scientifically valuable to damage,” Pam says. “Instead, we found out that we can use high-intensity X-rays to investigate the tooth rings instead.”

“Not only is this non-destructive, but it gives us the ability to investigate all of the cementum, not just a small slice of it.”

The team first demonstrated this technique in previous research focused on two of the earliest known mammals, Kuehneotherium and Morganucodon. These were shrew-like, insect-eating animals that had already developed some of the crucial characteristics that define mammals.

“Morganucodon and Kuehneotherium had already evolved two of the three key traits that make mammals unique among animals,” Pam explains. “They had just two sets of specialised teeth, and a middle ear complex capable of detecting high frequency sound.”

“We assumed that they must have also had the third, warm-bloodedness, but our work showed that wasn’t the case. We revealed much longer lifespans for these fossil mammals. As lifespan and metabolic rate are closely related in mammals and reptiles, this suggested they were physiologically different to their modern relatives.”

Following the research, the exact timing of when ancient mammals made the move to a more modern lifestyle remained an open question. The researchers needed mammal fossils from across the entirety of the Jurassic if they were to have any hope of answering it.

By counting the rings in the teeth, the scientists were able to work out the lifespan of different mammals. © Newham et al. 2024

To find the fossils they needed, the researchers turned to the collections of museums across Europe. This included the Natural History Museum’s Early and Middle Jurassic collections which were ‘invaluable’ to the researchers.

“The success of this project was only possible because of the exceptional collection of jaws and teeth at the Natural History Museum, London,” Pam says. “While they were collected many years ago, and have already been used in many different studies, the development of new technology means they still have so much to tell us. That’s so exciting!”

Scans of these teeth revealed the shift in mammal life history across the Jurassic. Early mammals, like Morganucodon, had relatively constant levels of growth, suggesting that their lives may have been more like today’s small reptiles.

The shift towards a more modern lifestyle first appeared in the Middle Jurassic mammals, which had a growth spurt in their youth that tailed off once they hit puberty. Growth rates increased into the Late Jurassic, but they were still growing more slowly and living longer than their modern relatives.

But not all mammals were following the same trend. Closely related animals from different environments had subtle differences in their life history that may reflect different pressures, just like mammals today.

It would take millions of years after the Jurassic for the modern mammal lifestyle to fully assert itself and become the default for species across the world. The team hope to investigate other groups of Mesozoic mammals to build up an even more detailed picture of this time, and perhaps to apply their research to other animals as well.

“Our technique offers a lot of potential, both to other animal groups, and to other fields of study,” Pam says. “We are currently interested in studying populations of fossil animals at times of high environmental stress and change, especially with application to current climate change.”

We're working towards a future where both people and the planet thrive.

Hear from scientists studying human impact and change in the natural world.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media