A gap in a distant cloud has allowed astronomers to peek inside a developing solar system.

Among the hot clouds of gas are signs of the first solids appearing during the first stage of planets coming into being.

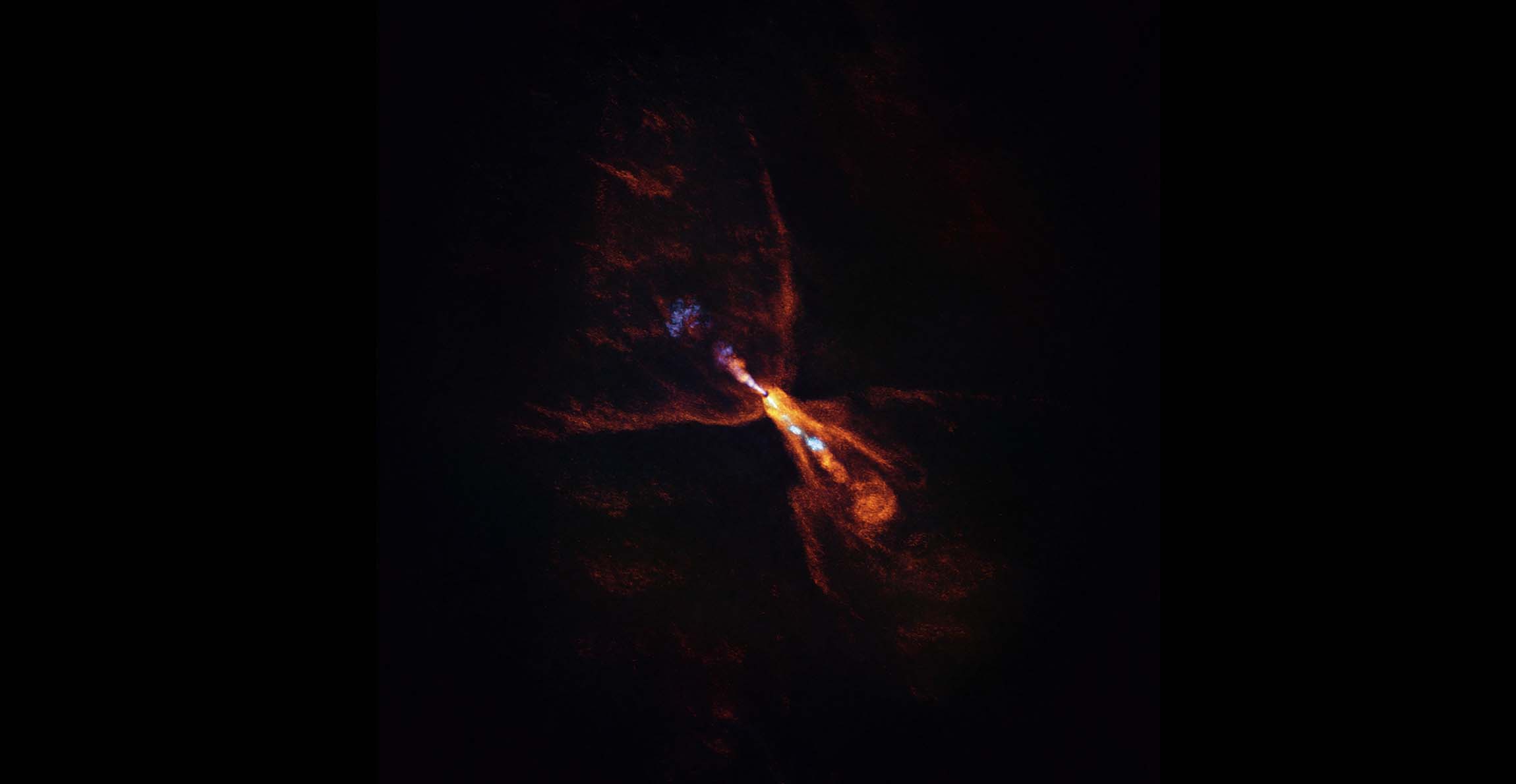

The telescope image shows carbon monoxide (in orange) blowing away from the star HOPS-315, while the blue jet is silicon monoxide. These gaseous winds and jets are common around young stars. © ALMA(ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/M McClure et al.

A gap in a distant cloud has allowed astronomers to peek inside a developing solar system.

Among the hot clouds of gas are signs of the first solids appearing during the first stage of planets coming into being.

Astronomers have captured a snapshot of the dawn of a new solar system.

Almost 1,400 light years away from Earth, HOPS-315 is a star at the very beginning of its life. Clouds of surrounding gas are collapsing into the star, powering the fusion reactions which will burn brightly for billions of years.

While this gas shroud normally stops anyone from peering at the growing solar system inside, there’s a gap in the cloud facing in Earth’s direction. By bringing together a telescope network called the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers were able to get front row seats for the formation of HOPS-315’s first planets.

The findings of their research, led by Professor Melissa McClureopens in a new window, have now been published in the journal Nature. She says that while developing planets have been seen before, they’ve never been found at such an early stage.

“We’ve always known that the first solid parts of planets, or ‘planetesimals’, must form further back in time at earlier stages of the protoplanetary disc,” Melissa explains. “Now, for the first time, we’ve identified the earliest moment when planet formation is initiated around a star other than our Sun.”

Co-author Professor Merel van ‘t Hoffopens in a new window describes the images taken by the telescopes as “a picture of the baby solar system”.

“We’re seeing a system that looks like our solar system did when it was just beginning to form,” adds Merel. “This system is one of the best that we know to actually probe some of the processes that happened in our solar system.”

Chondrite meteorites such as the one which fell in Winchcombe, UK, in 2021 can reveal the conditions of the early solar system, but only up to a certain point. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

When it comes to our own solar system, most of the knowledge about its early years comes from studying meteorites known as chondrites. These space rocks are made of the same material that went into the first planets, but have remained relatively unmodified since. This provides scientists with a time capsule of the early solar system.

One of the most important materials these meteorites contain is known as calcium-aluminium-rich inclusions (CAIs).

The dating of CAIs has revealed that they’re over 4.5 billion years oldopens in a new window. This makes them the oldest known solids in the solar system. Scientists think they formed from the clouds of gas that surrounded the early Sun, known as a protoplanetary disc.

As well as dating the solar system, these materials also reveal the conditions in which the planets formed.

CAIs only form in temperatures of at least 1,300 Kelvin, or just over 1,000°C. This extreme heat explains why planets closer to the Sun, like Earth and Mars, are full of rocks and metals, while those further out are made of lighter materials that quickly evaporated.

As more solids began to form, they started to clump together under their own gravity until they became planetesimals. As these bodies got bigger, their gravity became stronger, attracting more material and eventually leading to the formation of the planets we know today. The bits of rock and matter left over became asteroids.

But exactly how the planets formed has remained a mystery. To answer this, astronomers are looking to distant solar systems that are developing in a similar way to our own.

The telescope observations suggest solid minerals are condensing around HOPS-315 in a region that is twice as large as the distance from the Sun to Earth. © ESO/L Calçada/ALMA(ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/M McClure et al.

Searching for signs of CAIs forming is difficult, as it’s expected to only last for around 160,000 yearsopens in a new window – a blink of an eye in the life of a star.

To raise the chances of finding a star that’s starting to form its own system, researchers have been looking towards stellar nurseries. These giant clouds of gas are so dense that parts of them are collapsing in on themselves and producing vast numbers of stars.

Some of the closest nurseries to Earth are found in a region of our galaxy known as the Radcliffe Waveopens in a new window. This 9,000 light year long belt of gases contains many familiar stars and constellations, such as Orion and Taurus.

It’s within the molecular cloud of Orion B that scientists have spotted HOPS-315. This star is at an incredibly early stage of development, having formed probably within the last 150,000 to 200,000 years.

The star is so young that it’s still surrounded by a cloud of gases known as a protostellar envelope. Most of these gases will end up as part of HOPS-315, but a fraction will end up making the star’s protoplanetary disc which will then go on to form new planets.

By peering through a gap in the envelope, ALMA and the JWST were able to investigate the conditions in the developing disc. They detected the chemical signatures of gases like silicon monoxide as well as crystalline silicate minerals.

These materials only exist at high temperatures, conditions that are hot enough to also allow CAIs to form. This makes it likely that the first solids are already condensing around HOPS-315, and that the star’s first planetesimals have either already started forming or will shortly.

While there are still many questions about the early development of solar systems, this research shows that stars like HOPS-315 can provide the evidence astronomers are looking for.

Find out in our latest exhibition! Snap a selfie with a piece of Mars, touch a fragment of the Moon and lay your hands on a meteorite older than our planet.

Open now

Discover more about the natural world beyond Earth’s stratosphere.

Expand your knowledge with our on-demand course Rocks in Space. Explore the wonders of asteroids, comets and more with our expert-led, online course.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media