The passenger pigeon was once the most numerous bird in the world.

In the mid-1800s, billions of these birds were flying over the forests of eastern North America. Yet in just half a century, they’d disappeared entirely.

The rapid decline and eventual extinction of the passenger pigeon was a rallying cry for the conservation movement in the early twentieth century.

The passenger pigeon was once the most numerous bird in the world.

In the mid-1800s, billions of these birds were flying over the forests of eastern North America. Yet in just half a century, they’d disappeared entirely.

On 1 September 1914, a passenger pigeon called Martha died at Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden. She was the last known member of her species.

Several decades earlier, the idea of passenger pigeons going extinct was almost unimaginable. People living in North America in the first half of the nineteenth century would have been familiar with the sight of millions of these birds flying in waves that could be several kilometres long. Accounts from the time describe how huge flocks would even block out the Sun for hours as they passed.

So, how did a species that was so abundant become extinct?

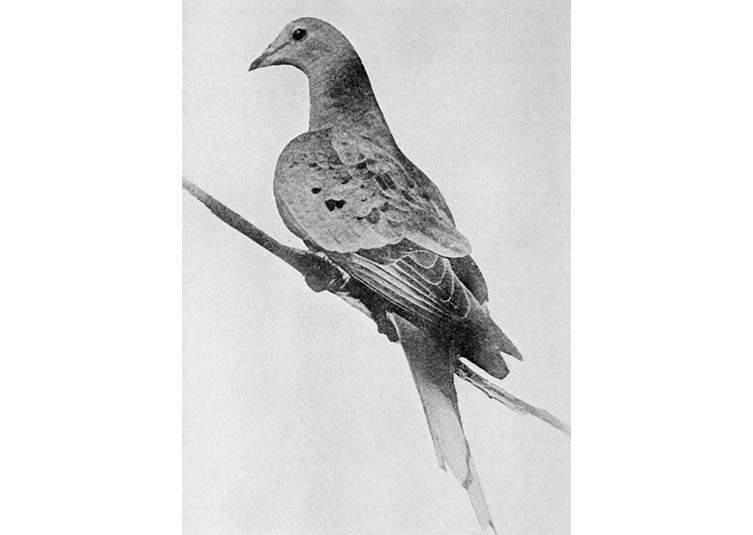

Martha – the last known living passenger pigeon – died at Cincinnati Zoo in 1914. Image source: Biodiversity Heritage Library. Photographed by Enno Meyer.

As the passenger pigeon is no longer here for us to study, we’ve had to piece together a lot of what we know about it from witness accounts from more than a century ago.

It was about the size of a Eurasian collared dove. Unlike many other pigeon species, the males and females looked different. Males had a noticeable bright orange throat and chest and a bluish-grey head and back whereas females were a lot duller.

The scientific name of the passenger pigeon Ectopistes migratorius means ‘wandering migrant’ in Latin. It’s a fairly accurate name, considering the species’ nomadic lifestyle. They’d travel hundreds of kilometres in massive flocks in search of an abundant supply of food.

Passenger pigeons mainly lived in eastern North America. Their breeding range stretched from the Atlantic coast on the east to the Mississippi River further west and from the Great Lakes in the north to Kentucky and West Virginia in the south. But outside the breeding season, they ranged even more widely, crossing into the western USA and Canada.

Their distribution largely coincided with tree species that were important to them.

Mainly the red oak, white oak, American chestnut and the American beech, which they relied on for mast – the collective name for the fruit produced by forest trees.

Passenger pigeons relied on fruit from red oaks, white oaks, American chestnuts and American beeches. © fotomaton2023/ Shutterstock

Many pigeon and dove species are territorial and don’t tend to congregate in groups.

This is in stark contrast to passenger pigeons. These birds travelled in extremely large flocks ranging from tens of thousands to hundreds of millions of individuals. Often flocking in search of forests with rich supplies of mast.

Passenger pigeons also nested in large colonies that reportedly stretched across kilometres of forest. Many people described the incredible, deafening sound of these. In fact, their numbers were said to be so great that large branches would break under the weight of the birds.

With passenger pigeons long gone, it’s impossible to know their actual population size. Instead, we try and estimate based on eyewitness accounts.

Many estimates suggest there were between three and five billion individuals. But some claims are as high as 10 billion.

Hein van Grouw, our Senior Curator of Birds, says, “it’s hard to say how numerous passenger pigeons would have been. The numbers we have are all estimates based on observations at the time, and some people may have slightly exaggerated the numbers to make them seem even more impressive.”

“But there are many stories from that time that say when a flock came over it was completely dark. Flocks were several kilometres long and several hundred metres wide.”

“Based on that we’d have to estimate how many birds in a flock and the number of flocks in total. So, numbers I don’t dare to say! But going off those accounts, it’s probably true that they would have been the most numerous bird species in the world at that time.”

Huge flocks of passenger pigeons would congregate in deciduous forests where there was plenty of mast to feed on.

As the saying goes, there’s safety in numbers.

Like many other pigeon species, passenger pigeons would have been a valuable food source for many local predators. Eagles, wolves and foxes would have feasted on them. People would have eaten them too, with Native Americans relying on them for food.

Many birds that nest in colonies, such as terns, will actively defend their nests against predators. But there’s no evidence to suggest passenger pigeons did this. Instead, their numbers were so great that natural predators probably wouldn’t have even made a dent in their colony size.

Plus, travelling in a huge flock while migrating would have made it hard for birds of prey to pick out a single individual. So being in a huge colony would decrease the predation risk for an individual bird.

Passenger pigeons were able to sustain their huge numbers thanks to the large amount of food available to them when the deciduous woodlands of the eastern USA were still intact.

Many predators, including eagles, wolves, foxes and people, relied on passenger pigeons as an important food source.

There’s never usually one determining factor that drives a species to extinction. This is true for passenger pigeons.

Although their numbers dropped most noticeably in the second half of the nineteenth century, evidence suggests their decline began long before this.

As Europeans colonised the eastern shores of North America and then moved westwards, more people began to encroach into the territory of passenger pigeons. This eventually led to their demise.

Habitat loss likely had the largest impact. By the late 1800s, almost half of the USA’s native forest had been destroyed for building materials and to clear land for agriculture.

The passenger pigeon’s entire lifecycle relied on specific trees. The birds required vast areas of forest to nest, roost and feed. As people cut down more woodland, the number of places large enough to house the pigeons rapidly decreased.

Overexploitation was another significant factor in their extinction. They were a popular target for hunters. Some records say their flocks were so big that you could fire one shot into the air and several birds would fall to the ground. The ever-growing human population not only considered them a tasty food source but also used their feathers to stuff pillows.

Competition for the tree mast also increased around this time. Many native animals, including passenger pigeons, ate mast that had dropped from trees onto the forest floor. But the growing pork industry meant they were now competing with feral pigs for this food source.

As early as the mid-1700s, people began to realise that passenger pigeon populations weren’t the size they once were. But their population decline was more widely noticed between the 1850s and 1890s, during which the human population of the USA grew threefold.

When flock sizes began to shrink, the population went into freefall, as the pigeons had evolved to survive in larger flocks. With only a few individuals remaining, the population was unable to recover naturally. The last reliable record of a wild passenger pigeon was in Ohio, where it was shot in 1900. Then 14 years later, the last known individual, Martha, died in captivity.

This illustration from the 1870s by Smith Bennett shows passenger pigeons being hunted as they fly over Louisiana. Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.

The passenger pigeon has joined the dodo and the woolly mammoth as potential models for de-extinction. The Great Passenger Pigeon Comeback, an initiative by Revive & Restore, seeks to bring back the species and return it to the woodlands of the eastern USA.

The team believe bringing the species back could also play an important role in promoting cycles of forest regeneration. By breaking branches, the birds would have opened up spaces in the tree canopy. These gaps let more sunlight through, creating a greater diversity of forest habitats, which in turn supported a wider range of wildlife.

The passenger pigeon is long extinct and nothing short of time travel can reverse that, but de-extinction initiatives could create a living replica of the species. This would involve using a close living relative – in this case, the band-tailed pigeon.

The process would involve extracting passenger pigeon DNA, most likely from museum specimens, and inserting it into the genome of a living band-tailed pigeon. The living birds would then breed and eventually hatch a passenger pigeon.

Some people believe that bringing species back could restore the important role these extinct species once played in the environment. But de-extinction projects are controversial. Others argue that we shouldn’t bring back species that are long gone.

“The issue is that passenger pigeons need huge areas of woodland,” says Hein. “We can’t just release them into North America because their habitat isn’t there anymore. We’ve destroyed most of it. We’d bring them back and they’d likely spend their life in a zoo because we don’t have the environment to release them into.”

“The other issue is that species extinctions might not seem as big a deal if people think we can just bring them back. Conservation initiatives may suffer. The problem is, what’s brought back is never the true species, it’s just a replica. It may look like a passenger pigeon, but genetically it is not, as it will carry the genetic material of the host species. The reality is once they’re gone, they’re gone and there’s no bringing them back.”

Bringing the passenger pigeon back from extinction would involve inserting its DNA into the genome of a living band-tailed pigeon. © Hayley Crews/ Shutterstock

In the USA in 1900, Congress passed the Lacey Act, which was the country’s first wildlife law designed to protect endangered species. The law was passed in response to growing public concern over the plight of the passenger pigeon. It prohibited the trade of illegally killed animals.

Although conservation efforts came too late to save the passenger pigeon, the species is often viewed as being a call to arms to address the wider loss of North American biodiversity.

Throughout the twentieth century, public awareness of environmental issues grew until the Endangered Species Protection Act was eventually passed in 1966.

“The extinction of the passenger pigeon gave us a clear warning that no matter how numerous a species might be, it is still possible for it to disappear because of our actions,” says Hein.

“We see it today with other species that were once abundant, whose populations are now a fraction of what they once were. We should see this as a sign that we need to be far more careful with our actions and try to do things in a sustainable way. Although passenger pigeons vanished over a century ago, they continue to serve as a stark reminder of the impacts we can have on the environment.”

Check out our tips on how to help your local birds.

We're working towards a future where both people and the planet thrive.

Hear from scientists studying human impact and change in the natural world.

Explore our on-demand course on the Biodiversity Crisis and learn how you can help.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media