Would you explore the murky depths of an underwater cave in search of venomous creatures? Museum researchers take on the risk and enjoy the challenge.

Dr Bjoern von Reumont goes to extreme lengths in his pursuit of venom © Bjoern M von Reumont

Cave diving can be the ultimate thrill, but it is a sport with a deadly reputation.

Despite strict safety protocols, diving without any natural light through twisting tunnels and cramped spaces is a fatal one-way journey for around ten experienced cave divers every year.

For one man working at the Museum, this risky activity goes beyond sport and is part of his job. Dr Bjoern von Reumont regularly puts his life on the line in pursuit of one of nature’s most dangerous defensive adaptations.

What lies beneath?

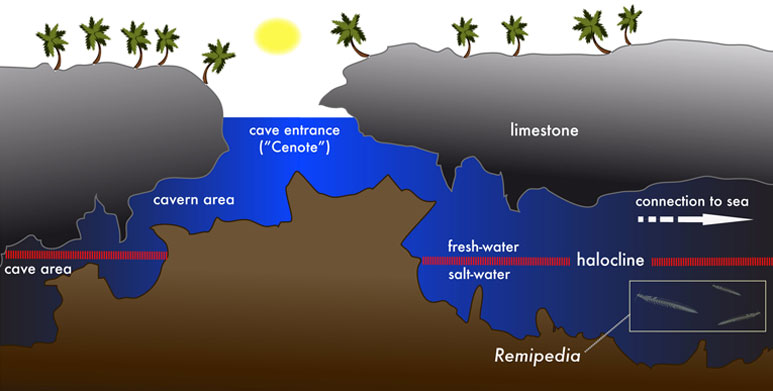

Beneath the lush jungle and ancient Mayan ruins of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula is a world that is little known.

Few people are aware that remote freshwater sinkholes provide gateways for scientists like Dr von Reumont to study venomous species.

Unfortunately the window for discovery in this area of the world could be prematurely closed by increased pollution and exploitation for tourism so Dr von Reumont is keen to explore as much as he can in the field.

To navigate these underwater caves, he follows a safety line with lamps illuminating the jagged rock formations directly in front of him. Visibility is often reduced as sediments get disturbed and clouds of gas are released by decaying material at the bottom of the cave.

Scooping up a sample in the depths of an anchialine cave © Bjoern M von Reumont

In 2013 this field work led a team of scientists from the Museum to confirm the existence of the world’s first known venomous crustacean.

The blind, cave-dwelling creature is known as a remipede and uses its highly toxic venom to liquefy its prey before ingesting the soupy remains.

Fortunately for Dr von Reumont, the largest specimen of remipede is only four centimetres in length and the animals reserve their venom for feeding on crustaceans, not scientists.

The world’s first known venomous crustacean, the remipede © Bjoern M von Reumont

Zoologist Dr Ronald Jenner affectionately describes the remipede as a 'centipede in a swimsuit'.

The head of the Museum’s venom team enjoys sharing tales of milking centipedes for their venom in his hotel room during field trips, and storing the venomous bounty in his refrigerator at home before bringing the animals to the Museum for further study.

A hazardous job

Dr Jenner concedes that the hazards of searching for centipedes on Putney Heath, dodging dog poo and wasps’ nests can’t compete with his colleague Dr von Reumont's dangerous underwater missions, but both scientists are advancing our knowledge of venom.

Milking a centipede for its venom is a precision task © Bjoern M von Reumont

The majority of venom research focuses on snakes, spiders, scorpions and cone snails - because humans are most likely to have dangerous encounters with these species. Scientists have focussed their study on the venom of these animals so that they can develop treatments for bites and stings.

But not all venomous species can hurt or kill a human, and Dr Jenner’s team at the Museum are focussing on comparative venomics, studying what he refers to as 'neglected venomous species'.

Using the most advanced technology available the team studies centipedes, remipedes and bristly marine worms known as polychaete annelids.

In 2014 Dr Jenner, Dr von Reumont and their colleague Dr Lahcen Campbell published a paper describing the identity of venom genes expressed in bloodworms, which are polychaetes commonly used as fish bait. They looked at the toxic cocktails different species use to suppress their prey in the hope it would show how venom has evolved.

Bloodworms are commonly named after the haemoglobin in their cells, which is visible through their pale skin

Evolving venom

The theory of convergent evolution describes how animals that have evolved independently in different lineages can have remarkably similar adaptations. This is important in the study of venom where unrelated animals such as snakes, centipedes and marine worms can share toxins.

Dr Jenner remarks on this:

'One of the mysteries all venom researchers want to solve is, why, in the event of independent evolution of venom, are there so many striking similarities?'

According to Dr Jenner, the creatures that have evolved venomous defences are diverse, but they all target the same parts of their prey’s physiology, such as the muscles and the nervous system. This could explain why venom toxins appear to converge, as they are all aiming for similar targets.

To get a full evolutionary picture the team plans to extend their research to investigate more of the world’s overlooked venomous creatures, including ribbon worms that glide through their marine environment on a trail of slime, and pseudoscorpions that are tiny denizens of leaf litter.

And so the search for these neglected venomous species continues, and while this task may not involve the obvious danger of cornering a komodo dragon, it is still a risky business - as any cave diver collecting a centipede in a swimsuit can tell you.

Schematic drawing of an anchialine cave, the remipede's natural environment © Bjoern M von Reumont

Venomics research

Learn more about the team's research into neglected venomous speces.

Cave centipede from hell

Read the news about the deepest-dwelling centipede ever discovered.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media