Walter was born into a prominent banking family, but he had little interest in finance.

Instead he pursued his childhood passion for collecting natural history specimens to a zenith.

Photograph of Walter Rothschild astride a giant tortoise.

Walter was born into a prominent banking family, but he had little interest in finance.

Instead he pursued his childhood passion for collecting natural history specimens to a zenith.

Born in 1868, Walter became interested in nature when he was very young. His family had moved from London to Tring Park in Hertfordshire, where he started collecting insects.

When he was seven he told his parents that he was going to 'make a museum', and by the time he was ten he had enough specimens to start one - in his parents' garden shed.

Alfred Minall, a joiner and journeyman on the Rothschild estate, acted as caretaker and taxidermist for Walter's early collections and became the Museum's first curator

But Walter's appetite for collecting both local and exotic species rapidly outgrew the modest construction.

Although his family disapproved of his interest in natural science, his father (the first Lord Rothschild) built him a museum on the edge of Tring Park as a twenty-first birthday present.

Three years later, in 1892, Walter’s Zoological Museum - now the Natural History Museum at Tring - opened to the public.

People outside the museum on the occasion of the International Zoological Congress, 1899

Although Walter served in the military, worked in the family banking business and was involved in politics, his first passion was always his museum.

He employed around 400 collectors during his lifetime and accumulated specimens from more than 48 different countries, many of which were new to Western science.

Collectors sent him animal specimens from around the world. Walter mainly stayed in Tring and focused on carefully studying the creatures he received and describing new species.

Ernst Hartert was appointed Curator of Ornithology (birds) from 1892 to 1930 and served as the museum's first director during that time. He travelled in India, Africa and South America and played an important role in making the museum a centre for scientific exchange.

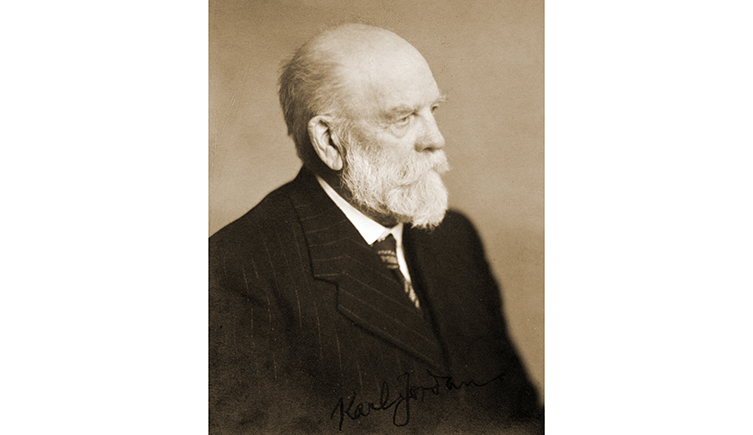

Karl Jordan was Curator of Walter's entomology collections (insects) from 1893, and the museum's director from 1930 to 1938. He described more than 3,000 new species, many from specimens sent to Tring by Walter's network of collectors, plus a further 800 in collaboration with Walter and Charles Rothschild.

In 1890 sailor Henry Palmer was sent by Walter to collect bird specimens from the Sandwich Islands (now part of Hawaii), where he documented the commercial egg-harvesting operations. Palmer's specimens were key to Rothschild's work on species that are now extinct or highly endangered.

As well as the thousands of specimens Walter put on display, the collection included over a million more used for research behind the scenes, notably 300,000 birds and over a million butterflies and moths.

In spite of his family's great wealth, the eccentric baron was sometimes short of money.

He sold most of his beetles to raise funds for his museum, and in 1931 a personal crisis forced him to sell his bird collection to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

Bird skin collection of Walter Rothschild leaving Tring, bound for the American Museum of Natural History

But his museum wasn't to blame for all his financial troubles. In 1931, Walter was confronted with a demand to pay for a debt 'not incurred on account of the museum'. Only after his death was it revealed he had been blackmailed for nearly 40 years by a peeress (who had once been his mistress) and her husband.

When he died at 69 in 1937, he left his remaining research collections, the public museum, its contents and the surrounding land to the Natural History Museum in London.

His collection is the biggest private natural history collection ever assembled by one person, and the largest bequest of specimens ever received by the Museum.

Walter's butterfly collections were later moved to London, and Tring became home to the bird research collections. Today, Museum staff working at Tring look after more than a million bird specimens, nests and eggs. Researchers from around the world travel to Tring to use this important collection.

As a collector Walter was drawn to both the unusual and the exotic.

A menagerie of exotic animals, Tring Park also became home to emus, kangaroos and zebras which were trained to pull a carriage.

Walter was even invited to drive it to the grounds of Buckingham Palace.

Zebra- and disguised horse-drawn carriage photographed outside the Royal Albert Hall

This bowler hat containing a wasp nest was found in an outhouse on the Rothschild estate in Tring.

Vespula vulgaris nest in a bowler hat currently on display in the Natural History Museum, London

Walter sent explorer Charles Harris to the Galápagos Islands, off Ecuador, to collect giant tortoises. Throughout his lifetime Walter kept a total of 144 live giant tortoises from Galapágos and Aldabra (in the Indian Ocean). His aim was in part to protect them from hunting and potential extinction in their native habitat.

Walter even leased the island of Aldabra for 10 years, to stop declining giant tortoise numbers by protecting them from hunting.

Transporting a giant tortoise (1897)

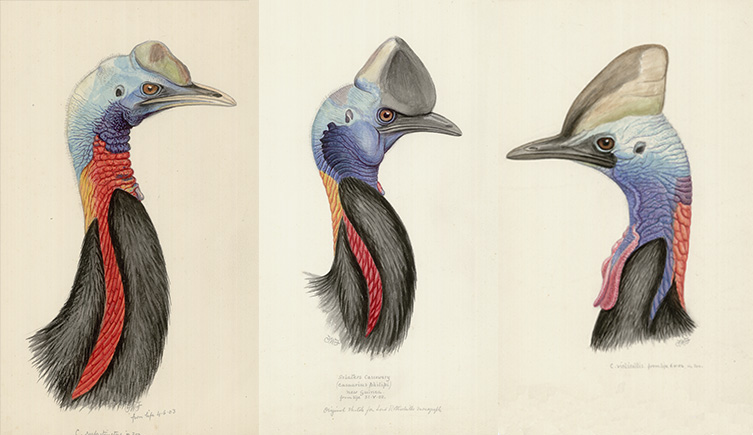

Walter was fascinated by the cassowary, a large, flightless bird found in Australia and New Guinea.

He kept 64 live cassowaries in nearby Tring Park, had portraits done of each, then had each one prepared as taxidermy when they died.

Walter wrote a monograph (a detailed study) based on observation of live specimens. Although he thought the birds' individual variation - especially their coloured wattles - indicated many species, there are only three species now recognised by science.

These portraits are just a sample of those prepared at Walter's request by artist Frederick William Frohawk (1861-1946).

Watercolours of cassowaries by Frohawk, prepared for publication in the Monograph on the Genus Casuarius

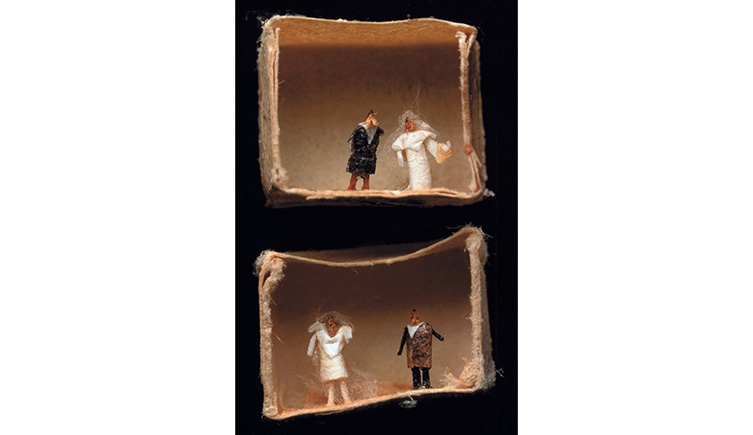

Two of the most bizarre specimens on display in the Museum at Tring are the dressed fleas. They come from Mexico, where they were made as souvenirs for tourists.

An interest in fleas ran in Walter's family. His brother Charles and niece Miriam both studied them. Miriam was also the first person to work out how fleas jump.

Dressed fleas from the collections of the Natural History Museum at Tring

Most of the 4,900 specimens on display in the Museum at Tring have been there since it opened to the public 125 years ago. In fact, some are still exactly where Walter put them many years ago.

Discover the world-class collection of animals and birds at the Natural History Museum at Tring, Hertfordshire.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media