Minerals are one of the building blocks of the planet. They are used in everything - from cars and mobile phones to toothpaste.

Not only do mineral species look different, but within each there are numerous colours, shapes and sizes - meaning every mineral specimen is unique.

There are over 5,000 known minerals, with around 100 more being discovered every year. Each mineral species varies because every one is made of different chemical elements, which are arranged in a variety of different internal structures.

The Museum houses around 185,000 mineral specimens, and 125 of them are featured in the newly redeveloped Hintze Hall.

Lu Allington-Jones, Senior Conservator at the Museum, had the delicate task of preparing a selection of them for the new display case.

Fragile nature

The majority of the specimens destined for display have never been seen by the public before, having spent years in the Museum's research collection. In some cases they needed a thorough clean.

Because each mineral is a unique substance formed of a combination of one or more chemical elements, it was not possible to use the same method to clean them all. Some needed a far more gentle hand than others.

'A quartz specimen was the only one robust enough to clean with a high-powered jet wash, because it is so hard and chemically stable,' says Lu.

'You couldn't even sneeze on other specimens without them falling to pieces.'

'Some minerals, such as mesolite and cacoxenite, have really fine, hair-like needles. They look as though they are furry and if you touch them they will break.'

For these, Lu used an air-puffer and tweezers, or putty on a cocktail stick, to remove individual pieces of dust.

'It was quite nerve-wracking,' she says.

Specimens like aragonite had to be cleaned with a laser. And some minerals, such as sulphur, are so sensitive that they can react to the slightest change in temperature or humidity.

Lu says, 'You can't handle sulphur because the heat from your hands will make it crack.'

Toxic minerals

Some minerals can even be dangerous to humans.

Although the minerals on display will pose no threat to visitors as they will be inside a sealed case, conservators had to take particular care.

'Some of the minerals are extremely toxic,' Lu explains, 'so we have to wear gloves and a mask when handling them'.

For example, stibnite contains antimony, which if ingested can cause symptoms similar to those from arsenic poisoning. If not handled carefully, it could have caused the conservation team serious harm.

Preserving the collection

In many cases, minerals form under the Earth's surface, away from air and light. The above-ground environment does not always suit certain minerals and can cause them to be extremely sensitive when brought to the surface. These minerals are often particularly sensitive when exposed to ultraviolet (UV), blue light or inappropriate relative humidity.

'Many people think that because rocks are usually hard and have lasted millions of years that they're stable, but in fact, many will oxidise or alter hydration state in our atmosphere,' explains Lu.

The Museum will protect the specimens using both glass that blocks the majority of UV rays and LED lighting to stop the display case from getting too warm.

If the temperature drops, condensation in the case could cause problems for some of the minerals. To combat this, silica gel is added as a means to absorb the moisture in the air and re-release it as the case's internal temperature begins to rise again.

Despite these efforts there is still the chance that some minerals will change over time.

Lu says, 'With a lot of them we have to accept that to some extent they're going to deteriorate.

'If you want to preserve them perfectly they should be locked away in a vault with no light or air, but then no one can enjoy them and no one can research them. So we aim for a balance.'

How to mount a mineral

The challenge of preparing the mineral display did not end with the cleaning process. Another complication arose when finding the best way to mount them within their case.

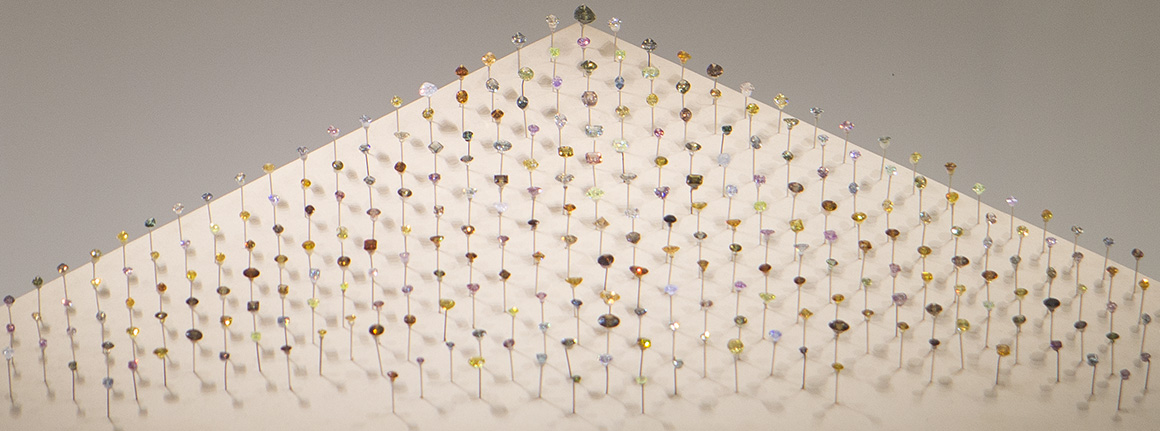

Robin Hansen, Curator of Mineralogy, explains, 'Every specimen is unique - some are harder whilst others may scratch easily, they're different shapes and sizes, they're different in how fragile they are and how heavy they are.'

A team of engineers designed special mounts for each specimen to rest on.

Robin says, 'The engineering team have done a fantastic job in finding a way to mount all of these different specimens - to cater for each one's challenges, but in a way that's going to be unobtrusive and look consistent.'

What's on display?

Although the visual impact of the display has played a significant part in the selection of minerals, their chemical complexities were also a deciding factor.

Robin says, 'They're going to be displayed according to complexity, so ranging from simple chemistry of a single element such as gold, silver and copper, through to more complex minerals in terms of their chemistry and atomic structure, like tourmaline'.

'Many specimens are going to be displayed high up. We had to choose minerals that were quite big so they could be seen,' explains Robin.

The more chemically complex minerals do not often form into crystals that are particularly big, so large specimens are more difficult to come by in the collection.

'Trying to find really big examples was, in some cases, really challenging,' she says. ‘Mike Rumsey, our senior curator in charge, did an amazing job searching our extensive collection to find the best selection of minerals to fit the theme, be big enough size, and create an eye catching display.’

See the minerals

The mineral exhibit will contain specimens from across the world and is intended for mineral experts and novices alike.

Robin says, 'Everyone will be able to appreciate the minerals for their beauty. We have also included some specimens for the collector connoisseurs.'

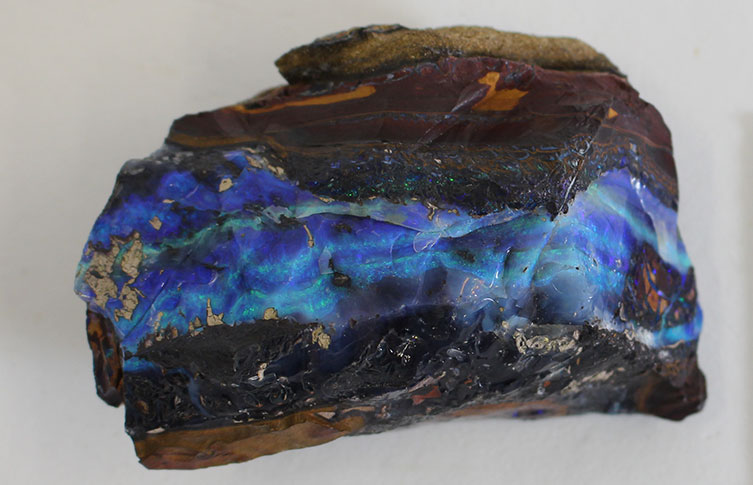

The case will be a rare opportunity to see some minerals, such as opal, in their natural forms.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media