Scientists surveying an ocean area targeted for deep-sea mining have shown how much is left to discover about the biodiversity of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, a five-million-square-kilometre region in the central Pacific Ocean.

The research, led by the Museum, has expanded the number of known species of mollusc living on the zone's seafloor from one to 21, with some species new to science.

According to Dr Adrian Glover, principal investigator of the Museum's Deep-sea Systematics and Ecology Research Group, by improving our knowledge of what is living in the area, it will be easier to monitor the effects of future mining.

'It is a simple truth that we cannot move forward on regulatory approval for deep-sea mining without fundamental baseline data on what animals actually live in these regions,' he says.

'Our work has highlighted obvious gaps in our knowledge, but also shown that with even relatively modest effort, we can greatly increase our understanding of baseline biodiversity.'

The 21 species of marine molluscs found by the survey belong to a variety of groups

The lure of the deep

The new discoveries were collected on an expedition to the eastern region of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone. Much of the zone is regulated for seabed mining, with several organisations investigating its economic potential.

The molluscs were found in samples taken on and in the mud surrounding the potato-sized polymetallic nodules that are widespread across the zone. These nodules are the target for any potential mining as they are rich in valuable minerals such as cobalt, copper, nickel and manganese.

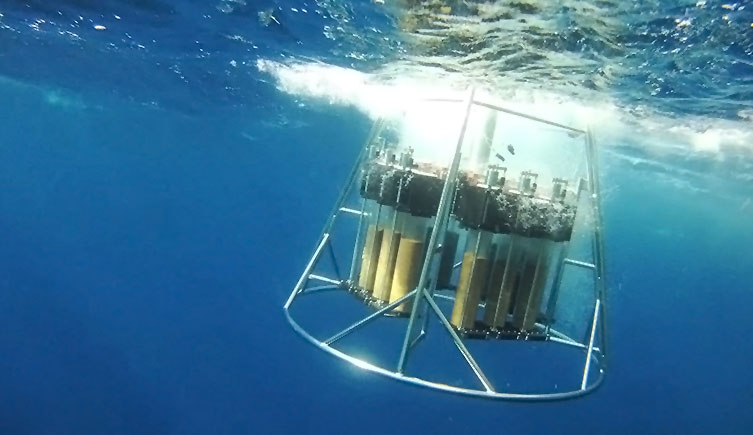

The sampler being recovered from a depth of 4,000m. Each tube contains a sample of sediment from the ocean floor.

DNA discoveries

Molluscs are a very diverse group of animals. Many different species live in oceans, such as mussels, clams and marine snails.

The researchers made a careful taxonomic study of the specimens collected, classifying the molluscs into their correct groups.

Dr Helena Wiklund, Museum researcher and lead author of the study, examined the DNA of the molluscs to confirm their identities.

'Despite over 100 survey expeditions to the region over 40 years of mineral prospecting, there has been almost no taxonomy done on the molluscs from this area,' she says.

Dr Helena Wiklund examining specimens at sea on the RV Melville in October 2013

Building an environmental DNA library

All the data and specimens from the study have been lodged at the Museum, with frozen samples housed in the Molecular Collections Facility. All information is also accessible online so that any researchers can easily access it.

The collected data can help future environmental regulation of any deep-sea mining, says Dr Glover. 'Now we are building up a genetic library of what is living on the seafloor, we could use the latest environmental DNA (eDNA) methods to monitor any changes to the distribution of these animals.

'Using just tiny samples of mud or seawater, you can search for the DNA traces of a species. But it's akin to forensic science - you can't use eDNA to find the criminals or species unless you have a baseline library of information to compare them to.'

Assessing environmental impacts

On 18 October 2017, the Museum will host the final meeting of the JPI Oceans international project called MiningImpact. The programme aims to analyse the long-term ecological consequences of deep-sea polymetallic nodule mining. For further details of this event see here.

Related information

- Read the scientific paper at ZooKeys

- Read news on further deep-sea mining zone research

- Visit the Museum's Deep-Sea Research Group

- Watch a YouTube video on sampling the Pacific Ocean abyss

Related information

- Read the scientific paper at ZooKeys

- Read news on further deep-sea mining zone research

- Visit the Museum's Deep-Sea Research Group

- Watch a YouTube video on sampling the Pacific Ocean abyss

Protecting our planet

We're working towards a future where both people and the planet thrive.

Hear from scientists studying human impact and change in the natural world.

Explore life underwater

Dive deeper into the work of the Museum's marine scientists.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media