During a 34-day expedition to a little explored area of the Pacific, an international team of scientists identified a number of new species living on the seafloor of newly-designated conservation zones.

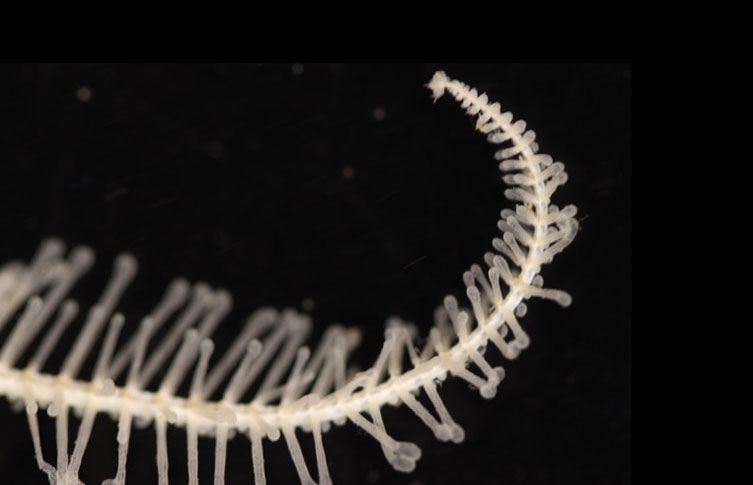

A new worm species discovered on the DeepCCZ expedition. Scientists will now describe the animal and give it a name. Image: Natural History Museum and University of Hawaii, DeepCCZ Project.

The deep-sea covers around 65% of Earth's surface and houses one of the planet's largest ecosystems. But it is also one of the least-studied environments.

Scientists recently carried out a survey of life on the seafloor of the western Clarion-Clipperton Zoneopens in a new window in the Pacific Ocean, a mineral-rich area that has attracted the interest of deep-sea miners.

The seafaring researchers identified an astonishing biodiversity, including a number of species new to science.

New abyssal animals

Museum scientists were part of an international group of researchers involved in the DeepCCZ missionopens in a new window to survey seafloor conservation areas of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ). Over 100 species of large animals were filmed and collected from Areas of Particular Environmental Importance (APEIs).

A number of animals were collected from the conservation zones so they can be studied. They included sea cucumbers, molluscs and polychete worms. Image: Natural History Museum and University of Hawaii, DeepCCZ Project.

Dr Helena Wiklund, lead scientist at sea and Museum scientific associate, said, 'I was amazed to see the diversity of animals down there, lots of beautiful and strange organisms and so many different species.'

Helena identified two new species during the expedition and believes that there will be more once all of the specimens collected have been studied. The two identified will now be analysed, described and given names.

Craig Smith, Professor of Oceanography at the University of Hawai'i and Lead Investigator of the DeepCCZ project, said, 'The diversity of life in these seafloor areas is really amazing.

'We found at least ten species of giant sea cucumbers, a huge squid worm never seen before in the Pacific Ocean, and all kinds of sponges. We also found other animals with really neat adaptations, such as sea cucumbers with long tails that allow them to sail along the seafloor.'

Exploring the seafloor

Dives to the seafloor were conducted using a new Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) called Lu'ukai (meaning 'sea diver'), reaching depths in excess of 5,200 metres. The vehicle was equipped to film and collect deep-sea animals, sediments and polymetallic nodules – potato-sized accretions of metal-rich minerals found on the seafloor.

A number of deep-sea animals were found in the Pacific APEIs. Researchers will analyse the collected specimens to identify any species new to science. Image: Natural History Museum and University of Hawaii, DeepCCZ Project.

Investigators from the Museum gathered information on the invertebrates found in the CCZ.

Dr Adrian Glover, DeepCCZ Principal Investigator at the Museum, said, 'There has been one big expedition and now we've got a couple of years to work on the samples. We're aiming to answer three questions - what's there, how widespread these animals are and how connected their populations are genetically.

'We'll do genetic sequencing of the animals and create a phylogenetic tree [to understand how they are related to each other], and also identify them using morphology.

Using the genetic data, scientists are able to look at biogeographic ranges of the animals. Adrian explains, 'We'll collect data from 20 or 30 individuals of selected abundant taxa from two or three sites and look at them in more detail to see how connected the populations are.'

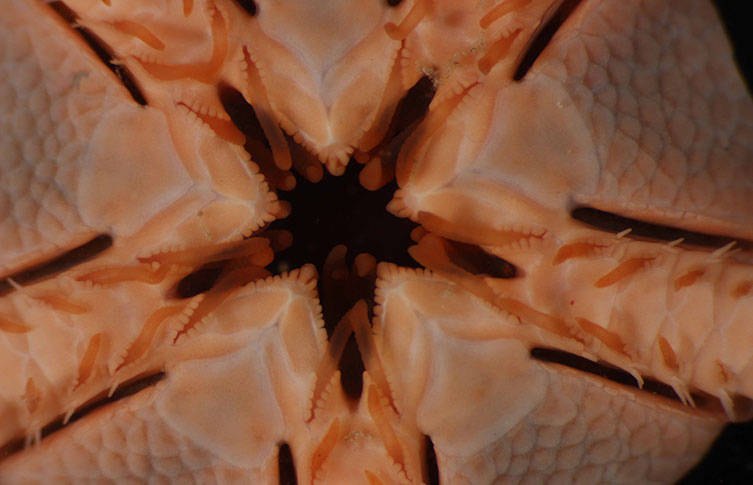

A close up of a brittle star mouth. Brittle stars are related to starfish. Image: Natural History Museum and University of Hawaii, DeepCCZ Project.

Dr Thomas Dahlgren, a researcher at the University of Gothenburg, is leading this genetic connectivity study. He is working closely with the Natural History Museum, where all of the genetic sequencing work is being carried out.

This area of the Pacific is the richest polymetallic mineral deposit in the world and there are numerous mining exploration claims associated with it. One key aim of the DeepCCZ project is to determine whether the newly-designated conservation zones are able to safeguard the region's deep-sea biodiversity from the destructive effects of mining.

The presence of larvae may be a positive indicator that mined areas could be conserved. Adrian says, 'Many marine invertebrates release larvae - so if these are moving around the seafloor, the mined areas could potentially be recolonised by larvae from the reserve areas.'

The data collected from this project are key for the International Seabed Authorityopens in a new window when it comes to them assessing how effective the Pacific's APEIs are.

Over a month at sea

The CCZ is one of the least studied areas of the planet. Adrian explains, 'These are completely unexplored areas of the ocean floor. It's a long way south of Hawaii, which is already very isolated. Effectively we know how deep it is and that's about it.'

Kirsty McQuaid, Regan Drennan and Dr Helena Wiklund prepare to set off on the DeepCCZ expedition aboard the Kilo Moana © Thomas Dahlgren

Helena spent 34-days at sea and was joined by two post-graduate students - Museum and University of Plymouth PhD student Kirsty McQuaid, and Regan Drennan, a student on the Museum-Imperial masters course in Biodiversity.

Of her time aboard the Kilo Moana research vessel, Regan says, 'The cruise was a fantastic and unique experience, and it made me truly appreciate the scale of these ecosystems and how much there is yet to discover.

'It was also great to be part of such a big team, with people from all different backgrounds and expertise working towards the same goal.'

Read more

- Explore the Museum's deep-sea ecology research

- Helena's blog about the opens in a new windowcreatures found on the Pacific seaflooropens in a new window

- Kirsty's blog on opens in a new windowprotecting the deep-seaopens in a new window

- Regan's blog about opens in a new windowlife aboard a research vesselopens in a new window

Further information

The team involved in the DeepCCZ expedition includes principal investigators from the University of Hawai'i, the Natural History Museum, the University of Gothenburg, Hawai'i Pacific University, the University of Montana, and Heriot Watt University.

The expedition was funded by the Gordon & Betty Moore Foundationopens in a new window, the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Researchopens in a new window, The Pew Charitable Trustsopens in a new window, and the University of Hawai'iopens in a new window.

Discover oceans

Find out more about how Museum scientists are studying the oceans.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media