Since the dawn of the space age in the 1950s, we have launched thousands of rockets and sent even more satellites into orbit. Many are still there, and we face an ever-increasing risk of collision as we launch more.

Thousands of dead satellites are currently orbiting Earth, as well as tens of thousands of fragments of space debris © ESA/ID&Sense/ONiRiXEL (CC BY-SA 3.0 IGOopens in a new window), cropped from originalopens in a new window

As long as humans have been exploring space, we've also been creating a bit of a mess. Orbiting our planet are thousands of dead satellites, along with bits of debris from all the rockets we've launched over the years. This could pose an issue one day.

What is space junk?

Space junk, or space debris, is any piece of machinery or debris left by humans in space.

It can refer to big objects such as dead satellites that have failed or been left in orbit at the end of their mission. It can also refer to smaller things, like bits of debris or paint flecks that have fallen off a rocket.

Some human-made junk has been left on the Moon, too.

Rockets can release lots of little bits of debris like paint flecks when they reach space, as seen in this GoPro video.

How much space junk is there?

While there are about 2,000 active satellites orbiting Earth at the moment, there are also 3,000 dead ones littering space. What's more, there are around 34,000 pieces of space junk bigger than 10 centimetres in size and millions of smaller pieces that could nonetheless prove disastrous if they hit something else.

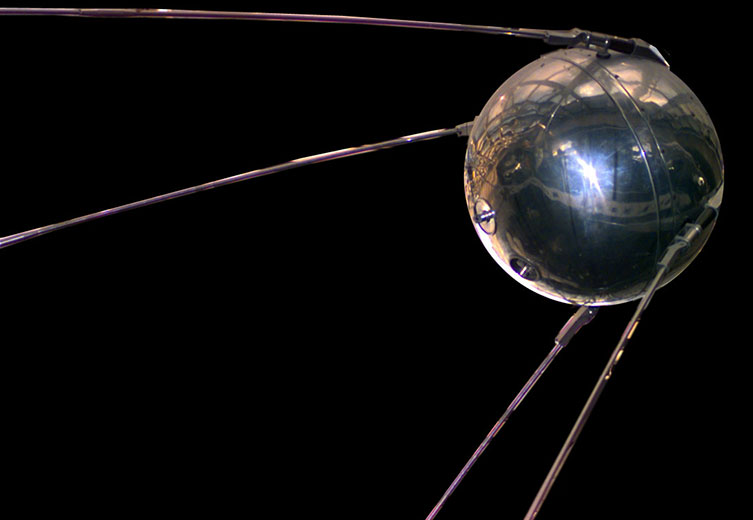

The world's first satellite, Sputnik 1, was launched by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957. Credit: NSSDC, NASA via Wikimedia Commonsopens in a new window.

How does space junk get into space?

All space junk is the result of us launching objects from Earth, and it remains in orbit until it re-enters the atmosphere.

Some objects in lower orbits of a few hundred kilometres can return quickly. They often re-enter the atmosphere after a few years and, for the most part, they'll burn up - so they don't reach the ground. But debris or satellites left at higher altitudes of 36,000 kilometres - where communications and weather satellites are often placed in geostationary orbits - can continue to circle Earth for hundreds or even thousands of years.

More than 5,000 rocket launches have placed satellites in orbit since the start of the space age in 1957 © SpaceX (CC BY-NC 2.0opens in a new window) via Flickropens in a new window

Some space junk results from collisions or anti-satellite tests in orbit. When two satellites collide, they can smash apart into thousands of new pieces, creating lots of new debris. This is rare, but several countries including the USA, China and India have used missiles to practice blowing up their own satellitesopens in a new window. This creates thousands of new pieces of dangerous debris.

What risks does space junk pose to space exploration?

Fortunately, at the moment, space junk doesn't pose a huge risk to our exploration efforts. The biggest danger it poses is to other satellites in orbit.

These satellites have to move out of the way of all this incoming space junk to make sure they don't get hit and potentially damaged or destroyed.

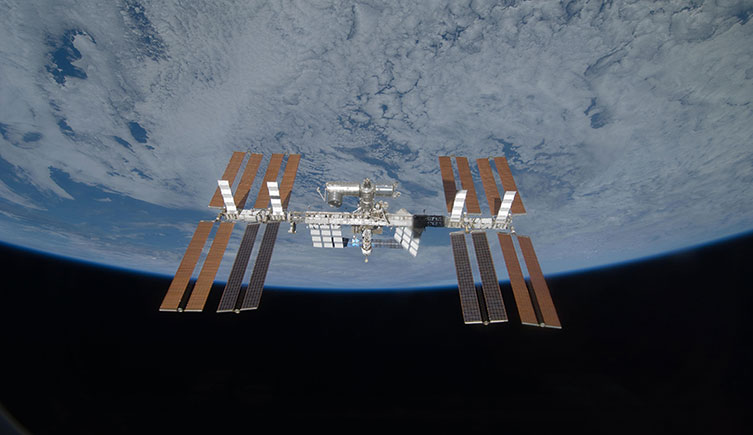

In total, across all satellites, hundreds of collision avoidance manoeuvres are performed every year, including by the International Space Station (ISS), where astronauts live.

The ISS has to carry out collision avoidance manoeuvres to avoid getting damaged by space junk. Credit: NASAopens in a new window.

Fortunately, collisions are rare: a Chinese satellite broke up in March 2021opens in a new window after a collision. Before that, the last satellite to collide and be destroyed by space junk was in 2009opens in a new window. And when it comes to exploring beyond Earth's orbit, none of the limited amount of space junk out there poses a problem.

Space junk in numbers

2,000 active satellites in Earth's orbit

3,000 dead satellites in Earth's orbit

34,000 pieces of space junk larger than 10 centimetres

128 million pieces of space junk larger than 1 millimetre

One in 10,000: risk of collision that will require debris avoidance manoeuvres

25 debris avoidance manoeuvres by the ISS since 1999

How can we clean up space junk?

The United Nations ask that all companies remove their satellites from orbit within 25 years after the end of their mission. This is tricky to enforce, though, because satellites can (and often do) fail. To tackle this problem, several companies around the world have come up with novel solutions.

These include removing dead satellites from orbit and dragging them back into the atmosphere, where they will burn up. Ways we could do this include using a harpoon to grab a satellite, catching it in a huge net, using magnets to grab it, or even firing lasers to heat up the satellite, increasing its atmospheric drag so that it falls out of orbit.

In 2018, Surrey Satellite Technology's RemoveDEBRIS mission practiced grabbing a satellite with a giant net. Watch the footage from Surrey Nanosats SSC Mission Delivery Team.

However, these methods are only useful for large satellites orbiting Earth. There isn't really a way for us to pick up smaller pieces of debris such as bits of paint and metal. We just have to wait for them to naturally re-enter Earth's atmosphere.

What’s the difference between a meteor and a meteorite?

What is the Kessler syndrome?

This is an idea proposed by NASA scientist Donald Kessler in 1978. He said that if there was too much space junk in orbit, it could result in a chain reaction where more and more objects collide and create new space junk in the process, to the point where Earth's orbit became unusable.

This situation would be extreme, but some experts worry that a variant of this could be a problem one day, and steps should be taken to avoid it ever happening. This idea was also popularised in the movie Gravity.

Will space junk be a problem in the future?

It could well be. Several companies are planning vast new groups of satellites, called mega constellationsopens in a new window, that will beam internet down to Earth. These companies, which include SpaceX and Amazon, plan to launch thousands of satellites to achieve global satellite internet coverage. If successful, there could be an additional 50,000 satellites in orbit. This also means a lot more collision avoidance manoeuvres will need to be done.

SpaceX's Starlink satellites are among several planned mega constellations of satellites © SpaceX (CC BY-NC 2.0opens in a new window), via Flickropens in a new window

In September 2019, the European Space Agency performed its first satellite manoeuvre to avoid colliding with a mega constellationopens in a new window. It is unusual to have to avoid active satellites.

By making sure that satellites are removed from orbit in a reasonable amount of time once they are no longer active, we can mitigate the problem of space junk in the future.

Earth's orbit allows us to study our planet, send communications and more. It's important that we use it sustainably, allowing future generations to enjoy its benefits, too.

Humans have intentionally and unintentionally left things on the Moon. Credit: R Karkowski, via Pixabay.

Things left on the Moon

Not only have we left a lot of space junk in Earth's orbit, there are objects elsewhere too, such as on the lunar surface. Some things were abandoned on the Moon, but others were placed there as mementos or time capsules. Here are some fast facts about what's been left on the Moon:

Three Moon buggies from Apollo 15, 16 and 17

54 uncrewed probes that have crashed or landed on the Moon

190,000 kilograms of material left by humans on the Moon

The first spacecraft and probes left on the Moon by different countries:

1959: Luna 2 (USSR)

1969: Ranger 4 (USA)

1993: Hiten (Japan)

2006: SMART-1 (Europe)

2008: Chandrayaan-1 (India)

2009: Chang'e-1 (China)

2019: Beresheet (Israel)

Some other strange objects left on the Moon:

1969: a golden olive branch (Apollo 11)

1969: art by Andy Warhol (Apollo 12)

1971: three golf balls (Apollo 14)

1971: a falcon feather (Apollo 15)

1972: a photograph of astronaut Charles Duke's family (Apollo 16)

Explore space

Discover more about the natural world beyond Earth's stratosphere.

Prepare for liftoff knowledge seekers!

But hold onto your helmets. Did you know we’re offering an on-demand course about Rocks in Space? Get ready to expand your knowledge to infinity and beyond.

Space: Could Life Exist Beyond Earth?

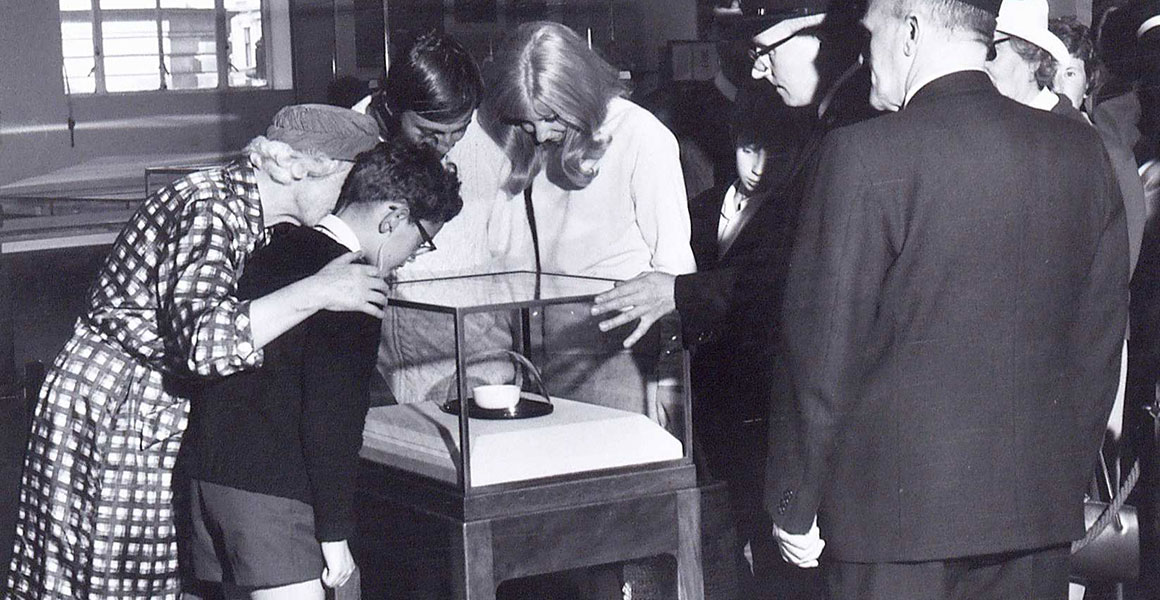

Find out in our latest exhibition! Snap a selfie with a piece of Mars, touch a fragment of the Moon and lay your hands on a meteorite older than our planet.

Open now

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media