Enquiries

If you want to know more about the science behind PREDICTS, then get in touch with the team.

PREDICTS pulls together species abundance data from studies around the world. These studies cover a broad range of taxa, including plants, fungi, invertebrates and vertebrates, to model how human activities impact biodiversity.

Over 500 researchers contributed their raw biodiversity data to the PREDICTS database that can be downloaded from the Museum's data portal. This data set is now taxonomically and geographically extensive and fairly representative.

This data set is openly available for anyone to use.

This map shows the data in the PREDICTS database. Each dot here is a site where biodiversity has been sampled. Dots are larger where more species were sampled. All sites are plotted as transparent dots, so dots that look opaque represent many sites near to each other. Land areas with the same background colour are in the same biome, meaning that they would naturally have the same broad kind of ecosystem.

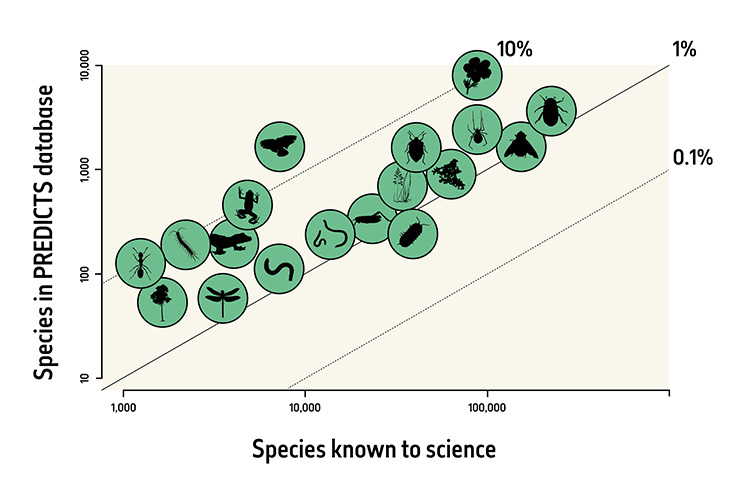

The PREDICTS database holds data from across all major terrestrial animal, plant and fungal groups. The database contains over 2% of all species named by science, with good coverage across most major groups.

Most of the data in the PREDICTS database are from arthropods, particularly insects, which is appropriate as insects are the most species known to science.

Most of the rest of the data are from plants, especially vascular plants (tracheophytes); this reflects their high diversity (over 400,000 species, many times more than the number of terrestrial vertebrate species) and crucial role as the base of food chains.

Vertebrates are over-represented relative to their diversity, but this bias is much reduced compared with other global data sets and indicators. We don't have as many data sets on fungi and non-arthropod invertebrates as we would like, but they are at least represented.

This broad representative coverage really matters, because different taxonomic groups don't respond the same way to human pressures.

Most other biodiversity indicators are based on a single taxonomic group such as vertebrates. Basing an indicator on only one group risks giving a misleading picture of the true state of nature.

The species represented in the PREDICTS data set.

The PREDICTS database is full of raw biodiversity data. For most studies, we know the number of individuals found of each species at each site.

This rich data means that we can calculate many different measures of biodiversity, including the total number of species (species richness) and the compositional similarity (how similar each site's ecological community is to near-undisturbed sites).

Combining models of abundance and compositional similarity lets us estimate the Biodiversity Intactness Index, an indicator of how much natural biodiversity remains, on average, across a region.

Find out more about how we calculate the Biodiversity Intactness Index.

To analyse the data from the PREDICTS database statistically, it is essential to account for the fact that the underlying data come from such a broad range of sources, focusing on different species groups and using different methods to sample them.

We do this using mixed-effects models to account for the hierarchical structure of the data. This is a robust, flexible method and allows us to assess different biodiversity metrics in response to different pressures.

An example of how researchers often study land-use impacts on biodiversity. The stars are study sites with degraded areas (red) and more natural habitats (blue). Biodiversity will be sampled in each of these sites and the average difference in biodiversity between natural and degraded sites (the effect size) is assumed to show the impact of the land-use change.

The most common way to study biodiversity change is by sampling multiple sites of different land use. This gives a spatial variation in biodiversity that is used to infer the impact that land use change has had over time.

The average difference in biodiversity between natural and degraded sites (the effect size) is assumed to show the impact of the land use change.

For example, a single study might look at birds in Uganda. This kind of dataset has enormous value, but it tells us only about how that specific group is responding in that specific region. It's just one piece of the puzzle of how biodiversity in general is responding to land use change globally.

If you want to know more about the science behind PREDICTS, then get in touch with the team.

Discover the science behind the Biodiversity Intactness Index.

Hudson et al. (2016) The database of the PREDICTS (Projecting Responses of Ecological Diversity In Changing Terrestrial Systems) project. Ecology and Evolution

Newbold T., Hudson L.N., Purvis A. (2015) Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity, Nature

Newbold et al. (2016) Global patterns of terrestrial assemblage turnover within and among land uses. Ecography

De Palma et al. (2017) Dimensions of biodiversity loss: Spatial mismatch in land-use impacts on species, functional and phylogenetic diversity of European bees. Diversity and Distributions

Newbold T., Hudson L. N. and Purvis A. (2016) Has land use pushed terrestrial biodiversity beyond the planetary boundary? A global assessment. Science