Take a stroll through the gardens of the past.

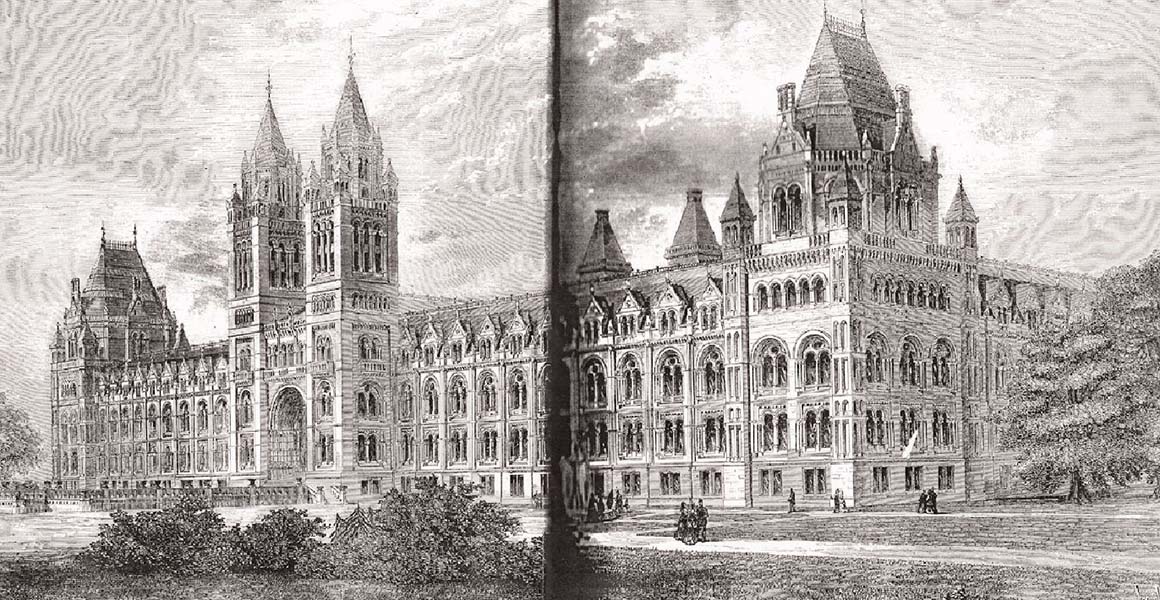

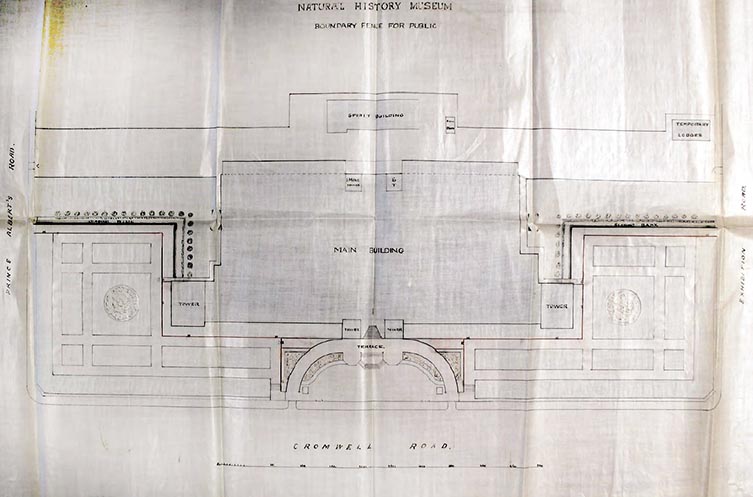

An early sketch of the planned Natural History Museum building and its grounds by architect Alfred Waterhouse, published on 4 January 1873 in The Building magazine.

The Natural History Museum first opened its doors on 18 April 1881, providing a permanent home for the ever-growing collection of natural history specimens originally housed in the British Museum.

Richard Owen, the first superintendent, envisaged a cathedral to nature that anyone could visit for free. He worked with young architect Alfred Waterhouse to create one of the most iconic buildings in London.

Originally our gardens were an area set aside for future expansion of the building. There was no intention to open them to the public. However, a lack of money resulted in a smaller building than planned and a need to landscape the gardens.

The east and west outdoor spaces started as formal gardens, but the addition of winding paths on the west side gave it a more natural feel.

Through the years the two sides of the grounds continued to develop independently.

1871

A large, landscaped garden existed in South Kensington before the Natural History Museum was built. The garden was opened in the 1860s and maintained by the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS).

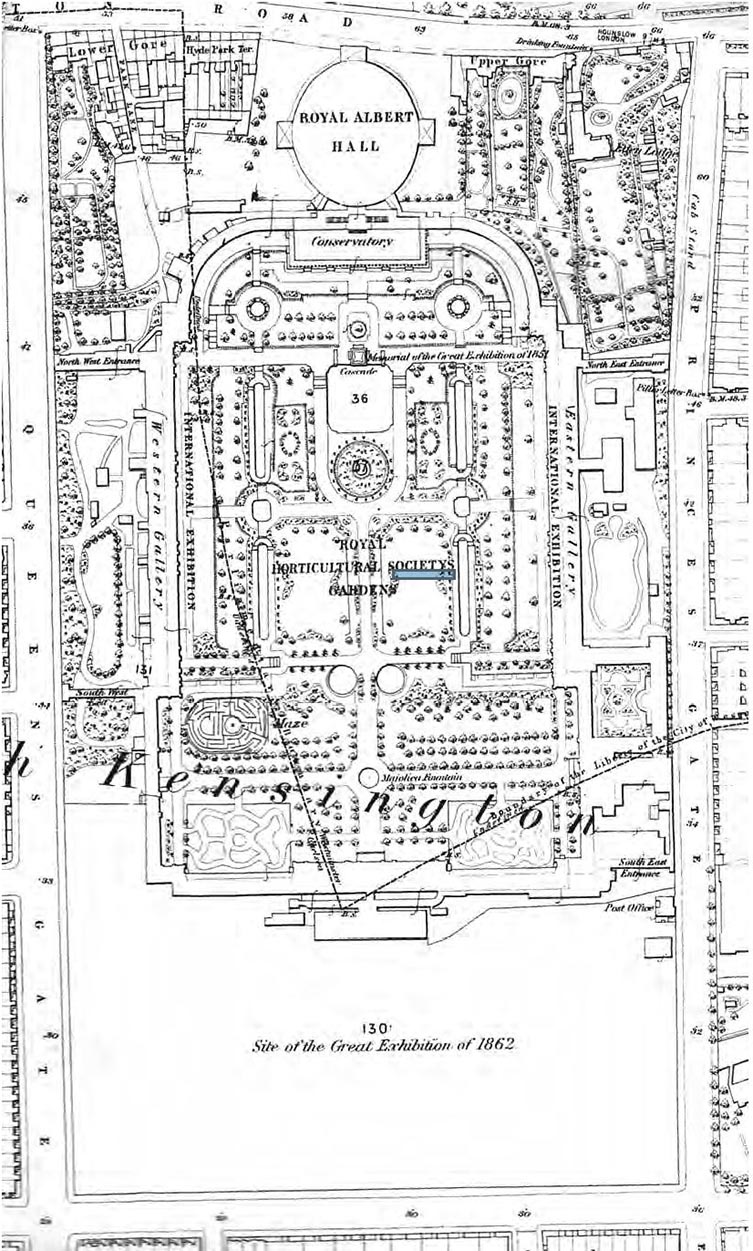

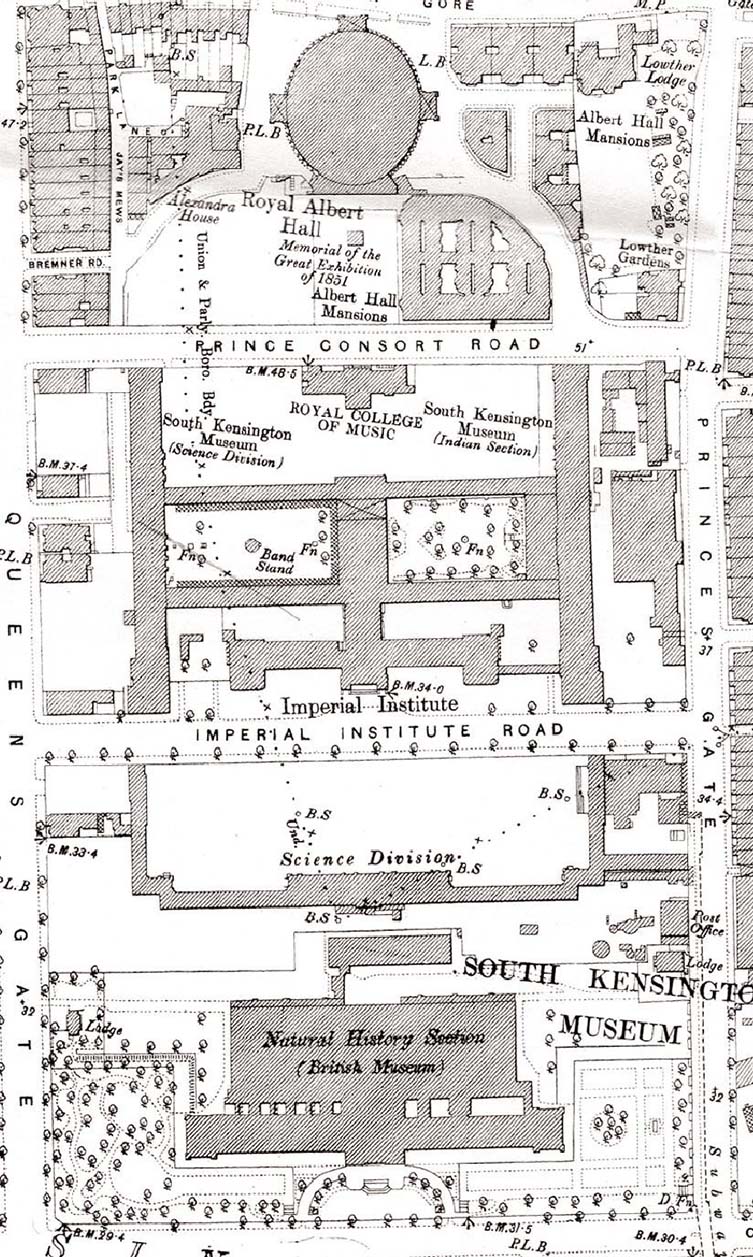

An Ordnance Survey map from 1871 shows the extent of RHS land before the Museum was built.

1873

A drawing of the proposed Museum by Alfred Waterhouse – shown at the top of this page – reveals that early garden designs were informal, with bushes and trees in clumps.

Work began on the new building in the spring of 1873. Landscaping went on hold for several years while the building was under construction, but by 1879 it had become practical to start work on the grounds.

1878

Myles Fenton, the General Manager of the Metropolitan Railway, wrote to the Trustees of the Museum asking if they had any objection to the creation of a pedestrian subway that would pass under Exhibition Road. None did and the Railway pressed ahead with the project. The tunnel was largely completed by 1885.

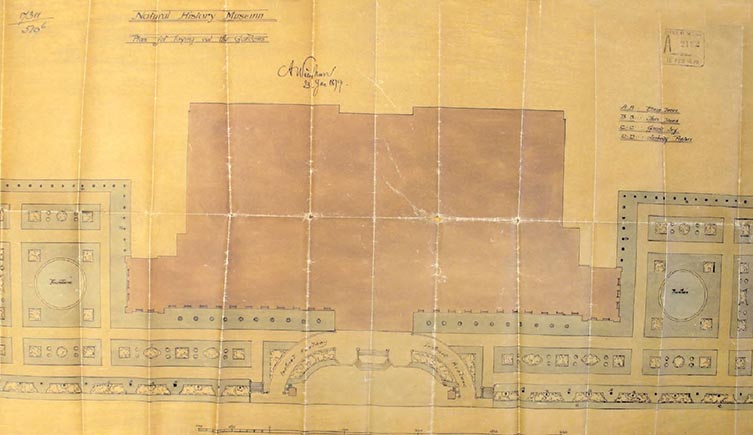

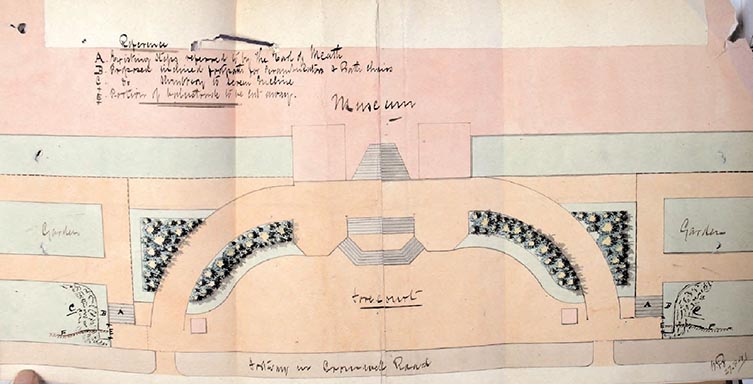

A plan from early 1879 shows a garden layout following the lines of the building, with two large ponds and ornamental trees.

1879

The image above shows a sketch of our grounds by Waterhouse. Two large ponds or fountains were proposed, flanking the building. Waterhouse also suggested providing additional structure using plane trees, Lombardy poplars, ground ivy and thorn bushes.

However, Commissioner of Works Gerard Noel didn’t approve Waterhouse’s proposed fountains and ruled that they should be replaced by flower beds instead.

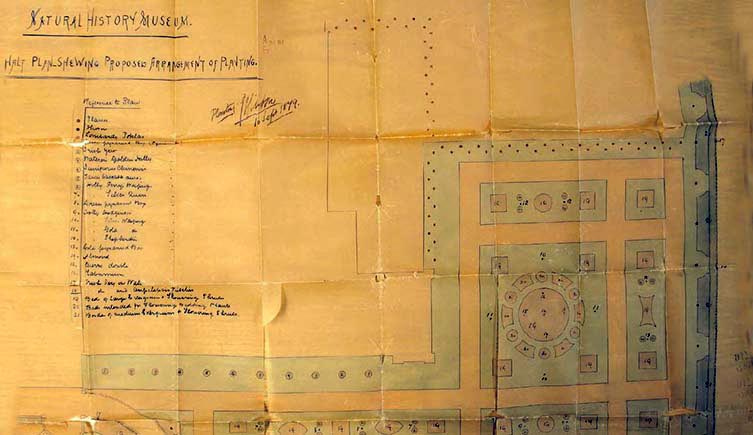

A drawing from September 1879 of new plans for our gardens.

A new proposal for the grounds was produced in September 1879 by the superintendent of St James, the Green, Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens. It shows 16 different types of trees, two varieties of ivy and beds of evergreen and flowering shrubs.

However, only limited planting was practical. Low maintenance and permanent alternatives, like the ornamental railings designed in 1885, were considered a better investment.

A photograph of our building at South Kensington taken in 1900, 19 years after it opened. Image: RIBA

1881

The Natural History Museum opened to the public on 18 April. A sense of how it looked upon opening can be gleaned from the photo above, which was taken in 1900.

This drawing from 1883 shows that none of the previous plans for our gardens were realised except for the layout of the paths.

1883

This plan of the grounds was produced after the Museum opened and shows that only the layout of the paths was achieved from previous plans.

A drawing of our entrance on Cromwell Road from August 1891, when a plan was put together to install ramps for greater access.

1891

In 1891 a plan was drawn up to allow access to the gardens via ramps next to the steps at the Central Entrance on Cromwell Road.

Very few activities had been permitted in the gardens until this date. Among other petty restrictions, walking on the grass was forbidden, as was the use of perambulators and riding in ‘barrows or velocipedes’. Children had to be under strict supervision.

People were now allowed to bring children into the gardens in prams and bath chairs, and the west side of the grounds was transformed from Waterhouse’s rigid geometry to snaking paths amid lawns and woodland.

An Ordnance Survey map of the South Kensington area from 1894. It shows the Natural History Museum at the bottom of the page, as well as the Royal College of Music and the Royal Albert Hall.

1894

In this Ordnance Survey map you can see the winding pathway through woodland on the west side that moved the gardens away from the first formal designs by Waterhouse.

Farms were established at the eastern end of the grounds and tended by staff and wounded soldiers. The Victoria and Albert Museum is visible in the background of this photo.

1914–18

To support the wellbeing of troops during the First World War, the we turned part of our gardens into allotments and a farm. The allotments grew potatoes, artichokes, cauliflowers and other green crops. The farm also boasted chickens, rabbits and eight pedigree black Sussex pigs.

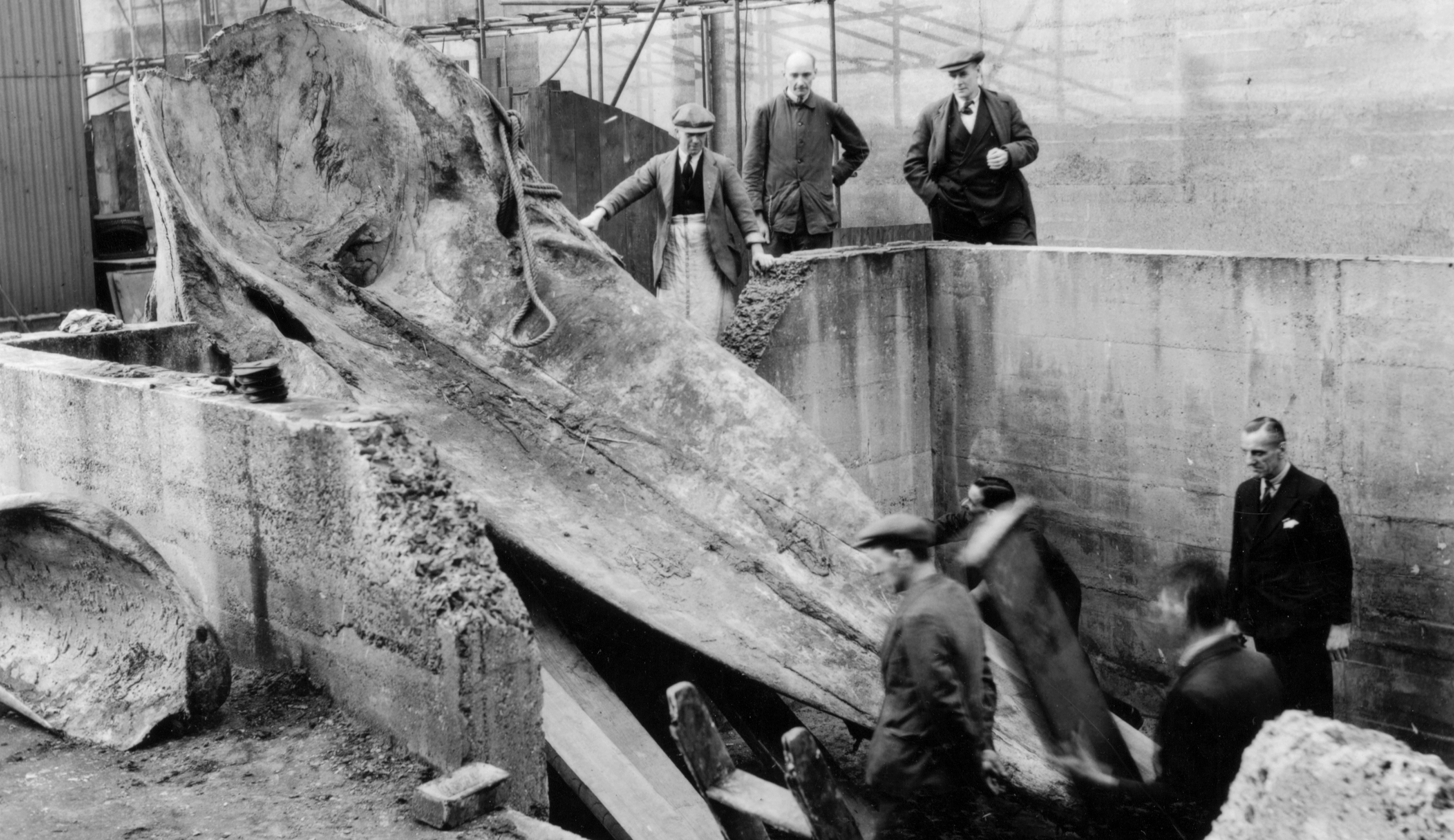

A sperm whale skull is dug out of a pit in our grounds.

1938

Whale carcasses were buried in sandpits between 1913 and 1938 in the northwest corner of the gardens, roughly where the Darwin Centre is now.

They were left to decompose so that their skeletons could be added to the collection. In the photograph above, Museum staff are digging up a sperm whale, before cleaning and placing the bones in the research collection, where they remain to this day.

1939

In 1939 a bunker was built beneath our gardens as a home for a regional war control room. After the war, this room was sealed. It remained closed until 1976 when the land was needed for a new extension to our main building.

In a plan from 1950, the area was shown as being occupied by a tennis court.

The east wing of the Museum as seen from Cromwell Road in 1975, showing the Palaeontology Building.

1976

Completed in 1976, the Palaeontology Building was the first major building project on the east side of the grounds. It covered the site of the tennis courts and the wartime bunker.

1995

A portion of the west garden was given a new purpose in 1995 – as a place to put habitat creation and wildlife conservation into practice, where visitors could learn about UK wildlife and where naturalists, students and our scientists could carry out research.

In an area covering a single acre, a mosaic of woodland, grassland, scrub, heath, fen, aquatic, reedbed, hedgerow and urban UK habitats was created.

The Wildlife Garden opened to the public on 10 July 1995.

The Museum’s then Director, Sir Neil Chalmers, said at the time, “our Wildlife Garden symbolises a unique interaction between two important elements which underpin our work: science and education. It creates for the first time an outdoor classroom combined with a living laboratory.”

The east part of the garden remained more formal and open.

An aerial view of the Wildlife Garden, taken in 2009.

2024

On 18 July, we opened newly transformed gardens to the public. For the first time, we united the east and west sides to create a five-acre haven for people and wildlife. Together, they tell the story of life on Earth.

The Evolution Garden explores the dramatic explosion of life on our planet and the major changes between then and now. Our Evolution Timeline, supported by Evolution Education Trust, takes visitors on an immersive journey covering more than 2.7 billion years on our planet. As you stroll through time, the landscape, rocks and plants change with you. Fossils, bronze sculptures and other features help bring the past to life.

This bronze sculpture depicts the small, shrew-like Megazostrodon rudnerae, which lived 200 million years ago and is one of the earliest known mammals. It’s just one of many features in our new Evolution Garden that help bring the past to life.

Crossing into the Nature Discover Garden, supported by The Cadogan Charity, the focus shifts to the wildlife on our doorsteps today. Here, scientists will monitor and study how urban nature is responding to change, while you can stop, look and listen to the nature around you.

We’ve doubled the area of native habitats within our grounds and increased the pond area by 60% to better support a diversity of animals and plants.

Creating a garden where nature can thrive but that’s also accessible to millions of visitors each year took years of planning and consultation. We also set ourselves ambitious sustainability goals. Every decision was scrutinised against what would be best for existing and future wildlife.

Visit our new gardens

Our gardens follow the story of how life on Earth has changed over time, from the days of the dinosaurs through to today.

Open daily

Take a guided tour of our gardens

Join us on our immersive Gardens Tour: Journey Through Time and Nature, and step into a world where nature, past and present intertwine.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media